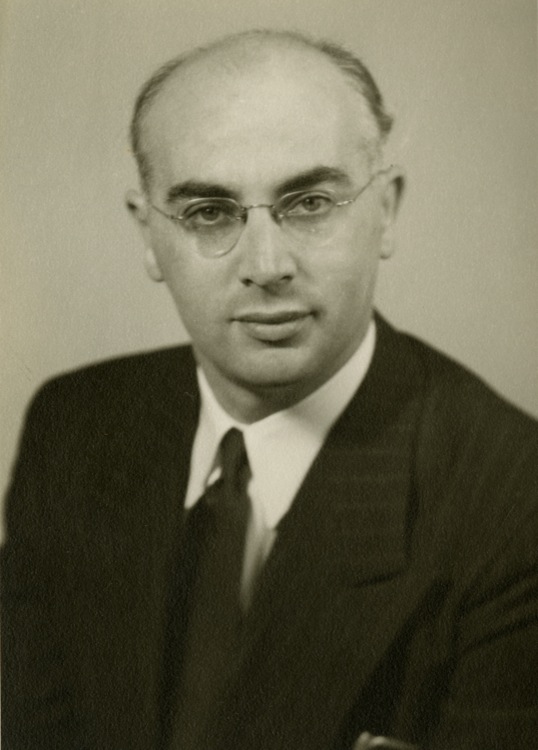

Victor Egert

1911-2005

Victor Egert was born in Eisenstadt, Austria on April 20, 1911. Victor lived with his parents, his brother and his sister in Vienna, Austria until he was 22 at which time he took a job in a carpet factory about 20 miles outside of Vienna. He worked there for several years until the Anschluss in early 1938 when he and the other few Jewish men working at the factory were fired. He moved back to Vienna for a few months before going with his sister-in-law to meet his brother in Luxembourg. After a short time in Luxembourg, Victor went on to Belgium where he lived and worked for a year and a half. As the situation with the Nazis intensified, he realized he needed to leave. In an effort to obtain the necessary affidavit to emigrate, he wrote to anyone in the United States who shared his last name. Two families did send him affidavits, and he was on a boat on his way to New York City in January 1940. He lived and worked for less than a year in both New York City and Chicago before accepting a job with Pendleton Wool Mills in Portland, OR in 1941.

Interview(S):

Victor Egert - 1992

Interviewer: David Turner

Date: October 15, 1992

Transcribed By: Alisha Babbstein

Turner: Would you begin please by just repeating your name and your birthdate and place?

EGERT: My name is Victor Egert. My birthdate is April 20, 1911.

Turner: And the place?

EGERT: I was born in Eisenstadt, Austria. Eisenstadt before the First World War was part of western Hungary. And in 1918 after the First World War the people were mostly German speaking and they voted to join Austria. Only the capital of that province, [city name], had more Hungarian people and they voted to go to Hungary. So that’s how I became Austrian. And my parents lived in Vienna, Austria. My grandmother was a midwife and when I was ready to be born my [mother] went to the little town which was about 30 miles from Vienna and the first two weeks I spent in Eisenstadt.

Turner: So really you were brought up in Vienna?

EGERT: Yes, we lived in Vienna. My father met my mother in Vienna and they got married there.

Turner: Can you tell me a little bit about where in Vienna you grew up, some of your early memories, who was in your family?

EGERT: We lived in the second part of Vienna. There were 21 parts in Vienna and we lived in the second part, which was next to the Danube canal, and across the Danube canal was the inner city. So it was a very nice neighborhood. We could walk across the bridge into the central part of Vienna.

Turner: Was that the Ringstrasse?

EGERT: The Ringstrasse yes. The Ringstrasse was surrounding the inner part of Vienna where all the palaces were, and all the museums and all the important churches and synagogues in the inner city.

Turner: What was your neighborhood like? What do you recall?

EGERT: It was a Jewish neighborhood. Many of the people that lived in that neighborhood had come to Vienna after the First World War. Part of Poland – Galicia – had many Jewish people and in 1918 they had a choice either to stay in Poland or to become Austrian citizens and many of the people in Galicia chose to become Austrian citizen and they moved to Vienna or some other parts of Austria. So a large part of the district, the second district, was populated by people who had moved to Vienna after 1918.

Turner: What kind of place did you live in? A house or an apartment?

EGERT: We had an apartment. There were five stories in the apartment and no elevator but we had good exercise.

Turner: Were you up on the top?

EGERT: No, we lived on the second floor. I think we had a small apartment and my father was a worker. He made a reasonable living.

Turner: What sort of work?

EGERT: He worked in a metal goods factory.

Turner: And who else was in your immediate family?

EGERT: There was my mother; and I had a brother who was two years younger than I, and my sister was nine years younger than I. There was seven years difference between my brother and my sister.

Turner: What do you remember of those early days in Vienna, say when you were still quite young? What was life like?

EGERT: Vienna was a very pleasant city. And like it is still is today we had lots of parks where we could go to. And they had very good schools. They had five years of primary education then three years of middle school. And most of the people choose a professional life and they would work in an apprentice shop. They worked for about three or four years and then they would get a degree. They had an examination, they got the degree, and they would work three or four more years as an assistant and then had another examination. So after approximately seven years they got their masters degree and they were permitted to open a store and do professional work like carpenter or furrier or tailor or any other profession.

Turner: Now is that the educational course that you traveled?

EGERT: I had my seven years of basic education and – I forgot to mention that a number of students after the basic education they went to gymnasium, which was four more years. It’s like our high school here. They got a degree there and after that they could go to the university and start out to be a doctor or a professor or whatever. I chose to become a textile technician so I got four years of high school education in a textile school. And after that I had an examination. I got the degree and I was able to get a job in a textile mill in an office and work with a manager in different ways.

Turner: Now what sort of things growing up did you and your brother do, and your family? To give me a picture of what your family life was like. Was it a religious family for instance? Or was it social? What was it? Give me a picture of what that time in Vienna was like.

EGERT: We grew up in the city of Vienna when we had a Social Democratic government, which is very similar to the Labor government in England. Its not a Communistic government. They had a capitalistic system but they believed in social laws for the working people. And they had government health insurance so every person in Austria was insured by the government and it worked very nicely. I hope they do it in this country, too, some day. We had social security. Austria was one of the first countries to have social security. And we had the old age insurance, and unemployment insurance. So all the social laws were passed by the government in Austria. And while the rest of Austria was more conservative and they elected a conservative government, the government we had in Vienna was Social Democratic until the very end – until Hitler came. And Vienna had about two million people and Austria as a whole had six million people so a third of the Austrian people lived around Vienna.

Turner: Quite a metropolitan.

EGERT: Yes. Vienna was the capital of the old Austrian-Hungarian Empire, which had 60 million people. And then after the Empire broke apart in 1918, Vienna still was there with the two million people but it had a much smaller country.

Turner: Can you tell me a little bit about what your mother and father were like? Can you recall what they were like?

EGERT: My father was a good worker and he took care of the family and we were not very religious. The government in Vienna, like I mentioned, was Social Democratic. And they were not very religious. They were anti-religious and so many of the people that grew up in Vienna had not much feeling for religion. And so the young people that grew up in Vienna, too, they were influenced by that public feeling. And while most Jewish people celebrated the High Holidays, but it’s pretty well like here in America that people go to the synagogue on the High Holidays but during the rest of the year they don’t go too much to the synagogues.

Turner: What would you and your family do for fun?

EGERT: We didn’t have much time for fun. My father worked five and a half days and he was pretty tired after that. And we didn’t have any cars. They might go for a walk. Once in a while they went to a movie. But otherwise we didn’t have much entertainment. Of course I grew up. When I was 14 years old and we had our graduation from the junior high school the mayor of Vienna, who was a Social Democrat, gave a big speech to us and he invited us to join the youth organization of the Social Democratic party. And many of the young people joined that organization. And it was more…For instance we had walks on every weekend; we went on hikes and we went dancing. And once a week on Wednesday we had a lecture about different subjects. And it was nice for young people to get together and feel that they are not alone.

Turner: This was in the Social Democratic organization?

EGERT: Yes. And of course they were anti-alcohol; you could not smoke or drink. It was a very nice organization and I would say the majority of the young people joined that organization because it offered a lot of things that young people wanted.

Turner: Now that was when you were 14?

EGERT: Yes, I was there from 14 to 18.

Turner: You mentioned your father a little bit. What about your mother?

EGERT: My mother was a good housewife and of course we didn’t have any washing machines. Our stove was coal fired. Anytime we cooked a meal you had to light a fire in the stove. The laundry was down in the basement. You had to wash the laundry by hand, which took more than half a day. And then she had to carry the laundry up to the 5th floor in the attic to hang the laundry up to dry. So most of the day was gone by the time she did one week’s laundry. That’s what my mother did. And the rest of the time she went shopping and cooking. Cooking a meal took about two or three hours. And of course she had children and she had to take care of the children. And she read the newspaper every day. After a while we had a radio so she could listen to the news and different programs.

Turner: Was there much talk in the family about conditions or ideas?

EGERT: I don’t think there was much discussion you know. My father spoke about different things that happened in his working place and my mother spoke about neighbors and the news that she heard from the neighbors. But we were not politicians.

Turner: Other family in Vienna?

EGERT: Yes, my father had a brother and he lived in the same apartment house and his family, too. It was very nice. He was an older brother. He was several years older and he had come to Vienna from Galicia before my father and then my father followed him. So they stayed together.

Turner: Did he have children? Did you have cousins?

EGERT: Yes. I had two cousins – a male and a female.

Turner: As you were growing up, was there much self-consciousness on your part about the relationships between Jewish people and Gentile people?

EGERT: There were no problems at all. The neighborhood where I grew up had a majority of Jewish people and there was no problem at all that I can remember. No conflicts. Vienna was a very pleasant city to live at that time. We had the Social Democratic government and Jews and Gentile were together in the government and they worked together and you couldn’t hear of antisemitism or anything at all until Hitler came.

Turner: So in high school that held up too?

EGERT: High school too. We had many Jewish people in our classes and in the grade school too, and junior high school we had quite a few Jewish students. And I never knew of any problems regarding religion or whatever.

Turner: When did you notice, or your family notice, that things were changing? That the social climate was changing. How did you know?

EGERT: When Hitler came to Austria.

Turner: Not before?

EGERT: Not before. We had a government like I mentioned, a conservative government in Austria, and they were very much opposed to Hitler occupying Austria. They wanted to be independent and most of the people in Austria agreed with that. And only after Hitler came to Austria then he took over and changed the whole atmosphere in Austria.

Turner: So before the Anschluss you did not worry about Hitler or the effects of Hitler?

EGERT: Not at all. And I don’t think anybody did. Nobody expected Hitler to invade Austria but he decided to do it and that was the end of it.

Turner: Now lets see, how old were you when he invaded Austria?

EGERT: I was 27 years old.

Turner: 27. So you were a working person?

EGERT: Oh yes. I worked in a textile mill when he invaded Austria.

Turner: What are some of the things that you did after you got out of school? Social things? Professional things?

EGERT: It was a very tough time. I was born in 1911 and when I graduated from junior high school I was 19 years old. That was 1930 and that was the depth of the Depression and it was almost impossible to get a job at that time. The unemployment maybe was 25- or 30% at that time. And so I did all kinds of jobs that were not connected to my profession. For three years I worked in an office where they handled bankruptcy cases and there were so many cases that they had to have a special office and I would say a very great percentage of the businesses in Austria went bankrupt during that time. And our office did the negotiation between the creditors and the people that owned the businesses. And then afterwards I got a job at [name] which is textile manufacturer; they made woolen fabrics. And they had also a carpet department and they made the carpet for one of the big hotels in New York when it was new. I forgot the name of it. They made beautiful carpets. And I worked in the fabrics department and we got along beautifully. I had my little apartment.

Turner: You lived by yourself?

EGERT: I was by myself. It was in the little town about 20 miles from Vienna and I went there by bicycle. On the weekend I went back to Vienna on the bicycle to be with my parents. And the manager in the fabrics department was Jewish. He was a Jew from Czechoslovakia and he was a very experienced man. And there was another Jewish man. He was the foreman in the spinning department. And there was another young Jewish fellow working in the same office I did so we were two Jewish people working in a factory. We were the only Jewish people in the town. And when Hitler took over then the other three people were discharged immediately. And the manager asked (the new manager was a Nazi from Germany who took over) and he asked me to stay around to train one of the Nazis to do my job. Somebody had to do that work so he asked me to stay on and teach that person. He happened to be the propaganda man of the Nazis in that little town and I was sitting next to him at the table everyday.

Turner: How did that feel? What was that like?

EGERT: Of course I didn’t worry too much. I had to do it and in the evening I cooked my own little meal in this little room. And when I went to bed I was afraid somebody might kick in the door – it was a wooden door – and so I put a chest of drawers in front of the door in case somebody would kick the door and I could jump out the window from the second floor and get away.

Turner: So you were afraid?

EGERT: I was afraid but nothing I could do about it. I couldn’t quit my job. They would have done to me in Vienna, you know, so I had to stay there. And I was the only Jewish person in that little town at that time.

Turner: What happened then?

EGERT: After about six or eight weeks the manager called me in and he said we have to terminate your job now and I got my six-weeks termination pay. The office employees in Austria, when they lost their jobs, they all got six-weeks termination pay. So I got my six-week termination pay and I went to Vienna. For about a couple months I was in Vienna.

Turner: How had things changed?

EGERT: Of course the Nazis were marching up and down the streets with their banner and shouting Nazi slogans and we had to watch that. It was not a pleasant situation but my father working in a metal goods factory, he kept on working because they needed the things that they were producing in that factory. And after I left Vienna he was still working in that plant.

Turner: Were there other things that you noticed occurring that were now changed? Any change in relationships among the people in Vienna that you noticed?

EGERT: Of course we didn’t feel it so much because we lived in a Jewish section of Vienna and most of our neighbors were Jewish. And the non-Jewish people, of course they had relationship with us, normal relationship with us. And I didn’t see much change there.

Turner: Did you feel as free to go across the bridge into the city?

EGERT: Yes, that was no problem until the Kristallnacht. I think it was in November. Then they really started to persecute the people and started sending them to concentration camps.

Turner: Where were you on Kristallnacht?

EGERT: I left Austria in August 1938.

Turner: Tell me how that came about.

EGERT: My brother, who was two years younger than I, had left for Luxembourg and he dropped us a line that he got across the border without any difficulties. His wife and a two-week-old baby were still in Vienna. So I went over to his wife and we decided to go to Luxembourg. We packed our things and the next day we left for Luxembourg. We went on the train to West Germany to Trier. And I was referred to a gentleman who was an attorney and he happened to be the president of the B’nai B’rith which was a Jewish organization in Trier and he invited us for dinner and he asked us how we were doing and he said, “How come all of the Jewish people are leaving Vienna?” And I said, “I don’t know why they leave, but you’ll probably hear about it.” And he could not understand it you know. He was still working in his job and he was Jewish.

Turner: What did you tell him?

EGERT: I said there is no future in Vienna and things don’t look too good. And he told us how to get across the border. The baby had a little red eye so he said there’s an eye doctor in the city of Luxembourg and we should go across and have the doctor examine the eye. So when we got to the border they ask us where we are going and I said we were going up to Luxembourg to have the eye doctor look at the baby’s eye. So the German border policeman said, “You have to leave all your things at the border and when you come back you pick them up again.” So I just happened to have bought a very nice new pair of shoes that were in that bag. So I left all these things at the border and we got across to the Luxembourg border patrol and we told them the same story. And they said, “Leave your passport here and when you come back you pick up your passport. So we left our passport there.” We got on the train and it was only about an hour’s ride to the city of Luxembourg, which is the capital. And we went to the Jewish Committee there and the Jewish Committee phoned the Luxembourg border police that they are going to take care of us. And we were going to come back to pick up our passports. So next day we went on the train again and went back to the border and picked up our passports and went to Luxembourg. And we stayed about two weeks in Luxembourg and then the Jewish Committee in Luxembourg, which is a small city, couldn’t take care of too many refugees so they suggested that we go across the border to Belgium.

They told us where there is a side road. They told us to take the bus to the border then go down to the side road and walk across that side road into Belgium. There was no border police on that little side road – a kind of path. So we did that. You know we didn’t have much to carry [laughs]. So we went across the border and took the train to Brussels. I’d like to correct myself – my brother stayed in Luxembourg, and his wife. I alone and a friend of mine that I met in Luxembourg went across the border. We took the train to Brussels and went to the Committee there and they gave us information about where to stay and where to rent a little room. They gave us a small amount of money for living expenses. And I lived in Brussels for, if I remember right, about half a year. There were quite a few young Jewish men in Brussels that came across the border. The Belgian government suggested that we should go into a working camp. They had different kinds of jobs there. It was on the northern edge of Belgium on the border of Holland, of Netherlands. And there were about 600 young Jewish people in that camp. And I got a job as a gardener. We planted little trees. It was a very nice job and we got pretty good food and we got even a little money. And every three weeks the bus would take us to Brussels for the weekend and we could spend two nights in Brussels and visit people that we have known and do things. And then go back again for another three weeks to the camp and work there.

Turner: This seems to me to be a drastic change in the way that – this seems almost like you were a prisoner, that you were no longer free?

EGERT: We were not prisoners but we were in a camp. The Belgian government didn’t want so many young people to run around the city without jobs and things so that’s the reason they suggested that be done. But it was a very pleasant thing. On the weekends when we didn’t go to Brussels we had musical entertainment and there were some people there that had worked in a major opera house and they even put on a little opera performance that taught us how to do it and it was very nice.

Turner: Did you feel that this was in any way antisemitic?

EGERT: No not all. No I think the Belgian government wanted to help us and wanted to teach us jobs, you know. The people were working there.

Turner: So who did you leave behind in Vienna?

EGERT: I left my parents behind and my sister. And my sister, several weeks after I had left, she went with a group of young Jewish people to Yugoslavia. And they were training there to become farmers and then go to Israel. But then when the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia they had to run away from that camp and got onto a barge to float down the Danube River. The Nazis caught up with them and they shot everybody on that boat. So that’s the last I heard of my sister. And when I was still in Vienna a friend of mine suggested that I go to the American consulate and get the telephone books from different cities and look up people with the same name that I have. I found ten people with the name of Egert in Washington D.C. and Los Angeles and Chicago and New York and one or two other cities. So I wrote to those ten people and told them about the situation and I ask them to send me an affidavit. Two of the people send me an affidavit, one in New York and one in Chicago. After I was in Belgium, half a year in Brussels and one year in the camp I finally got my papers and I got my visa to come to the United States. And I left in January 1940. I left by boat to come to the United States and I think two or three months later the German army invaded Belgium and I don’t think many of the Jewish people that had settled there survived.

Turner: My understanding is that you left somebody else in Vienna?

EGERT: Yes my parents.

Turner: And your sister. And your fiancé?

EGERT: Yes. My fiancé, if I remember, had relatives in London and they sent papers to her that she could come to London so she was lucky in that way.

Turner: So she was in London when you were in Brussels?

EGERT: She was in London when I was still in Belgium.

Turner: Were you able to write?

EGERT: We wrote two or three letters and then we lost contact. And when I came to New York I found out where her sister lived. Her sister had gotten to New York from Luxembourg – she was in Luxembourg too with her husband. They got to New York before I did and I found out where Ruth, my wife, was in London so we started to write to each other again.

Turner: How did things go for your parents in Vienna?

EGERT: Of course I tried to get papers for my parents too. But then after Kristallnacht in November 1938, all the Jews lost their jobs and they started to deport them to concentration camps. So there was no hope that my parents could come to the United States. My parents wrote me several letters while they were still in Vienna but then after they left that was the end of it and we lost contact. And I understand they disappeared in a concentration camp and didn’t survive. I wrote to the Red Cross here in Portland and they were going to find out exactly what happened to my parents.

Turner: How was it for you in New York?

EGERT: In New York. The Egerts that sent me the affidavit invited me to stay with them and I stayed with them for six months. It was almost impossible to get a job in New York in 1940. The unions were so strong and if a foreigner came to New York it was almost impossible to get into work where the union was active. The Egert who send me the affidavit was a furrier supplier. He had a store and he had some connection to furrier stores and fur makers. But he couldn’t get me a job so after six months I decided to go to Chicago where the other Egert lived who sent me an affidavit. He was the treasurer of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and he was also the president the B’nai B’rith in Chicago. And I stayed one week in Chicago and then it was suggested to me that I go to Rockford, Illinois, which is about 100 miles west of Chicago. And there’s a wool mill there. I went there and went to the chairman of the Jewish Committee there and he got me a job in the wool mill in Rockford, Illinois. And I worked there for a year. And I had my name with a textile employment office in New England and after a year they wrote me there’s an opening in Portland, Oregon at the Pendleton wool mills for a man with my qualifications and I should contact them. So I wrote to Pendleton Woolen Mills and I got a job here so I drove to Portland.

Turner: You had a car?

EGERT: Yes, I had bought a car. It was a very beautiful trip driving across the country. That was in 1941 and in [South] Dakota they were building the monument of the four presidents and I was able to stand on top of the head of Abraham Lincoln [laughing]. It was half finished then. It was a beautiful trip and then continued to drive along the Columbia River before the highway was built. It was very scenic. I have enjoyed living in Portland ever since – I have been here for 51 years now.

Turner: Did you remain employed by the Pendleton Mills?

EGERT: I worked for Pendleton Woolen Mills for one year in a Portland plant and then I went to Washougal, Washington for four and half years. Then when in 1946 Ruth came to the United States, after the war, we got married in Portland. I had time – I wasn’t married so I had lots of time – I joined the Mazamas and we went on hikes on the weekends. But I had enough time to do a second job. I took on a manufacturers representative job in my spare time. And I figured out I could make a good living there. So after we got married we decided to travel and see the United States, and it was great decision, you know. I did it for more than 40 years.

Turner: As a manufacturers representative?

EGERT: Yes.

Turner: Now I am not sure how that works. Did you work for a particular company?

EGERT: No I was an independent representative. At one time I represented 17 companies and I did it until I was 78 years old. But of course in the later years I had only two or three companies that I represented and I made a living and we didn’t have many expenses. First we lived in an apartment then we bought a duplex. The people that lived with us in the duplex, they took care of the property while we were gone so we didn’t have to worry. And after six or seven years we bought our home in the West Hills and we lived there for maybe 30 years.

Turner: I ask you to think back over this time in Vienna and emigration to the US eventually. What haven’t you told me yet about it? What experiences come back to you?

EGERT: I think most people were very helpful to us and they had lots of sympathy for people that were in trouble. You know, it was no trouble that was caused by us but by the Nazis. And of course then when the war started, America was against the Nazis too, they fought the Nazis so we had lots of sympathy among the American people.

Turner: When you were in Vienna after the Anschluss, was there much arrest of people without cause or beating or humiliation or were these things part of your daily life or not?

EGERT: In Vienna?

Turner: Yes, or anywhere?

EGERT: No. I had no bad experiences and like I mentioned to you we lived in a neighborhood that had quite a few Jewish population.

Turner: Somehow though it became clear that you should leave?

EGERT: Yes, definitely. I didn’t see any future after I lost my job and I see the Nazis were taking over and many of the neighbors of course lost their jobs and when they had the opportunity they were leaving Vienna to different countries. Many of them went to Switzerland across the border up to Italy or to Yugoslavia.

Turner: What lesson would you have us learn from all of this? What would you tell us?

EGERT: To visit the Anne Frank exhibition and you get a pretty good picture what happened during that time.

Turner: How would you say it has affected your life?

EGERT: To be honest if I had stayed in Vienna I probably would have had a small office job in a textile factory. Maybe a little better job a little later and it would have been a plain living. But when I came to America, I was able to make a real good living and live in a beautiful country. We had our own home. In Vienna I probably would have never had my own home. We would have lived in a little apartment all the time. But here I was able after just a few years to buy my home. So I had a lot of benefits by being able to come to the United States and live here.

Turner: I have run out of questions [directs floor to camera person or assistant]

Assistant: I was wondering if you kept in contact with the two people who sponsored you to come to the United States?

EGERT: Definitely yes, with both people in New York. And I am still in contact with the children of the people. And the Egert, Max Egert, from Chicago. He moved to Florida about ten years ago and he died last year. He was much older than I.

Turner: They were not relative?

EGERT: I could never find out. But the name Egert is not very usual, Egert [he spells it]. And when I came to Portland I was the only Egert in Portland and only three or four years later another small family came to Portland with the name of Egert. They phone me when they come here because I was the only Egert here that they found in the phone book.

Turner: So you made contact with them?

EGERT: We visited a couple times but we had different interests.

Assistant: Were you ever able to visit the other two in Chicago and New York after you moved here?

EGERT: Yes, I lived in Rockford, Illinois so while I worked there in Rockford I was visiting the Egerts in Chicago. They were very lovely people and they were very helpful. And we were corresponding all of the time. On the holidays we send cards to each other. Once or twice a year we wrote a little note about how we are getting along.

Turner I want to thank you very much for participating.

EGERT: Thank you for asking me and I hope I was helpful to whatever you are planning.