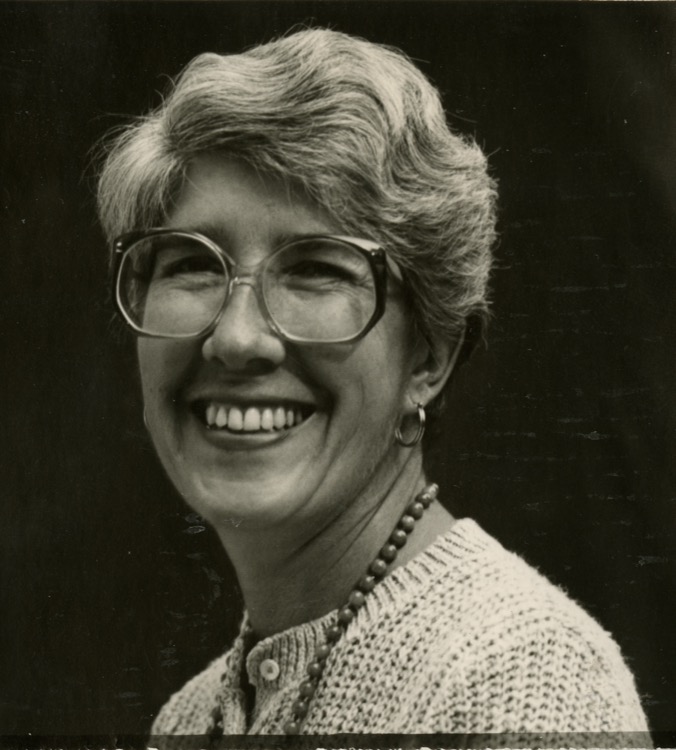

Rose Rustin

b.1932

Rose Rustin was born December 22, 1932 on a dairy farm in Silverton, Oregon, the tenth of eleven children of Walter and Elise von Flue. Walter was Catholic and Elise was a member of the German Apostolic Christian Church. Rose contracted polio at 18 months forcing her mother to leave the house with her new baby. Rose was raised by her older sister. She attended Evergreen grade school to the age of 13 and then got her GED.

Rose worked as a nanny and then at the Silverton Hospital as a kitchen helper and then nurse’s aid. She began studies at Merritt Davis Business School of Commerce, which led to a job in the business office of the hospital. Rose had a falling out with the church and left Silverton in 1957. She moved to Portland and worked at the Portland Clinic as a medical secretary and eventually as secretary to Dr. Arnold Rustin.

After 12 years in Portland, Rose entered Mt. Hood Community College nursing school. She became very close to Jean Rustin, Arnold’s wife, who introduced her to many things Jewish and cultural including National Council of Jewish Women (where Rose later became president). Jean Rustin died in 1971, and Rose and Arnold eventually married, and Rose converted to Judaism. She was president of Congregation Beth Israel, on the national board of NCJW, and a volunteer in many community organizations, including Neighborhood House. At the age of 62, Rose earned her bachelor’s degree in humanities at Marylhurst College. She has written a book about her father’s family (13 generations in Switzerland).

Interview(S):

Rose Rustin - 2005

Interviewer: Sharon Tarlow

Date: August 25, 2005

Transcribed By: Roberta Weinstein

Tarlow: OK Rose, here we are. And, this is fun for me actually. I’ve been thinking a little bit about what I want to ask you and, let’s just start with the fact that you were born in Silverton, Oregon. Let’s just start there with your family and childhood.

RUSTIN: Yes, I was born on a dairy farm in Silverton, Oregon. I was the tenth of 11 children. We were raised in a very religiously fundamental church community under the auspices of my mother. My father was born and raised a Catholic and didn’t interfere with the way that my mother raised us in this church. As one of 11 children, I would say it was a wonderful experience having so many siblings. We had our own softball team. We had our own singing group. We did lots of things as an 11-member team. We worked very, very hard on the dairy farm but our parents were extremely good to us; gave us all the freedoms to express ourselves within the confines of the church. It was a happy childhood. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized the elements that were missing in this upbringing.

Tarlow: So, well, let’s go back to your family a little bit. You said your dad remained Catholic the whole time. Now, was he a practicing Catholic? Did he go to church and all that?

RUSTIN: He did not remain a Catholic because in order to marry my mother, he had to choose; give up his Catholicism or give up my mother. He chose to give up his Catholicism to marry her. He had to join her church to marry her, which he did, but it lasted only a few years.

Tarlow: The church, not the marriage?

RUSTIN: The membership in the church. The marriage lasted and it was a relatively happy marriage despite my father’s long siege with alcoholism. He never returned to practicing his Catholicism actively. Primarily, I think, because shortly after my mother died, when my father was less than 60 years old (just prior to his becoming 60), he had a brief marriage with another woman, which last only six months. That, of course, made him a divorced man and made him question whether or not Catholicism could be his practicing religion. However, at a later age, when he entered the Catholic nursing home, The Benedictine Center, it was very obvious that this was home to him because of its Catholicism there.

Tarlow: And none of your brothers or sisters were Catholic?

RUSTIN: No.

Tarlow: They all were your mother’s religion?

RUSTIN: Right.

Tarlow: Ok, so tell me a little bit about what you had to do as a kid? What were your chores, even though you were among the younger ones?

RUSTIN: The chores were pretty much the same. My younger sister and I raised the calves that would become the cows in the dairy herd and that chore we absolutely loved. We became very attached to those would-be cows; they had their names, they had their own special barns, and they were like our pets. We also worked in the milk house washing bottles and cleaning milk utensils. At an earlier age, we actually carried the milk from the barn to the milk house in buckets as the milkers filled the buckets. We also raised hops and we worked in hop fields from April till September, often missing grade school to work in the fields. We raised chickens and we had to gather eggs, take care of the chickens, feed them (which we hated because we did not like chickens) [Tarlow chuckles].

Tarlow: What was a day like for you? Say you’re 10 years old or 12 years old and a typical day in the life of Rose Rustin. What would you have been doing?

RUSTIN: In the summer time or beginning in approximately April, we would take care of our calves first thing in the morning.

Tarlow: Which was what time?

RUSTIN: Oh probably somewhere between 6:00 and 7:00 am. After we had our chores done and I don’t remember the times that we worked in the barn carrying milk buckets. I was just told that’s what we did so my first remembrance, really, is of working with the calves. After we had the calves taken care of, the baby calves fed, etc., we would come in the house, wash up, change our cloths, eat breakfast and go to school. We were given approximately one half-hour after we got home from school at 3:30, quarter to 4:00, having WALKED home from the country school, to play. Then we had to go back to doing chores until supper time. After supper, you know, we did dishes and it was house things. There was not much play time. As summer progressed and school was out, we worked in the field all day long doing whatever was in order that season or time of the year.

Tarlow: And this was in Silverton? And what was the name of the grade school that you went to?

RUSTIN: Evergreen.

Tarlow: And then you moved on to high school. Did your life change much?

RUSTIN: We finished grade school at age 14 and, because our church did not want to see their children educated, we were not allowed to attend high school. But at about age 15, I think I was out of grade school about one year, I felt so strongly that I wanted more education, that I remember cutting out an ad in a magazine for a correspondence course that would give me a high school diploma. And I wrote for this person to come and talk to my mother to enroll me in the school. And I did this without telling my mother. When this man came to the door, I told my mother what I had done and I told her (and I knew that these were just empty words) but I told her if she did not enroll me in this school, I would run away. And I actually had planned what I would do when I ran away. But surprisingly, she agreed to do this for me and my younger sister. And we were given so many hours a day to study and do what we thought typical high school work. And after about three years, we finished the school and thought we were going to get high school diplomas but what we got was a GED and that was, that school work was simply sandwiched in with all the work that we had to do.

Tarlow: Now, what did you guys do for fun in your family when you were growing up? You worked hard.

RUSTIN: We worked very hard. But we were given frequent rewards for the work we did, with day trips. We never missed the Rose Festival experience. Every year we came down to the Rose Festival Parade on the back of the pick up with about a dozen kids. We went to Silver Creek Falls a lot. Brighton Bush Hot Springs. And every summer, my parents rented a house at Nelscott, that’s at the beach, for two months. And we could rotate a week at a time with friends at the beach at Nelscott and that was, of course, the highlight of our summers.

Tarlow: Now, your mom would be at the beach and your dad would be at home?

RUSTIN: No. The two younger kids, Marlene and I, would start those two months with a week at the beach with my mom and dad and we would take down all the things that the family would need for two months in the house that we rented. Thereafter, Mom and Dad were home and we were allowed to go to the beach now and then with one or two of the older sisters.

Tarlow: So, how much older is the oldest child in your family, than you?

RUSTIN: Lena was 13 when I was born, 14 when the youngest child was born.

Tarlow: So Lena was …

RUSTIN: Lena was my mother, for rather an unusual reason and that is when I was 18 months old, I contracted polio at the very time that my mother was giving birth to Marlene. When this happened, the doctors told my mother that she could not bring an infant into a home that had polio. So she was told to stay elsewhere with this baby, which she did, and my older sister, Lena, then became the mother of the house. And I’m not sure how long this lasted – but long enough so that I bonded with her as my mother. And thereafter, she played that role in my life and has really up until just recently when she began her time with Alzheimer’s and doesn’t remember any of those times any more. Only the good parts we had, but she and I had been at odds ever since I was a child.

Tarlow: Ok, so after you grew up and you got your GED, what happened? Did you leave Silverton?

RUSTIN: No. I left Silverton in 1957 at which time I would’ve been 25 years old. But from the time I was 17, I began to work outside the home for money. And my first job was as a nanny for a family in Salem during the state legislature when the father was a state senator and the mother was his secretary and I took care of their children during the legislature. I think that was for probably three months. After that I went to work for the Silverton Hospital as a kitchen helper and from there as a nurse’s aid. And when I had saved up a little bit of money, I started Business School while I was working.

Tarlow: And all the time you were living at home, and commuting, right?

RUSTIN: Yes.

Tarlow: Where did you go to Business School?

RUSTIN: Merritt Davis School of Commerce in Salem. That led to a job in the business office of the Silverton Hospital and in 1957, it gave me the confidence to move to Portland with a cousin who had just finished her training as an x-ray technician and we rented an apartment and secured jobs in Portland.

Tarlow: And so where did you live and what did you do?

RUSTIN: We lived in SE Portland on the top level of an old, old house where the rent was miniscule. This was in 1957 and my first job was at The Portland Clinic as a medical secretary. I worked there only six months before I got bored with being a secretary and not taking care of patients. Remember, I had worked in the hospital with contact with patients for a total of about four years.

Tarlow: Now, all this time, were you involved in the church that you were raised with? Did that still have meaning for you?

RUSTIN: Absolutely. I was still the obedient daughter. I went to church every Sunday. Even when I moved to Portland, I was driving up to Silverton to go to church every Sunday and would spend at least one night in my parental home. All the while, protesting that I didn’t believe in what I was hearing. I thought the church did not follow their Jesus, as they claimed they did. I remember my first protest was talking about the church being Paul, not Jesus, and having arguments with my mother but I didn’t truly leave the church until I was forced to by the church elders.

Tarlow: And I don’t know if we’ve mentioned the name of this church?

RUSTIN: The church is The German Apostolic. Christian.

Tarlow: So they kicked you out?

RUSTIN: They kicked me out because I defied the law of the church by cutting my hair.

Tarlow: How did your mom feel about that?

RUSTIN: My mom was dead by then.

Tarlow: Phew! Would you, you probably could not have done that?

RUSTIN: I don’t know that I would’ve been able to do that to my mother. And this is probably the key reason why I say that the greatest gift my mother gave me, as I reflect on my life, was her death, because it gave me the freedom to be free of the guilt that I would’ve had to pursue what I wanted to do with my life.

Tarlow: Well, let’s talk about that pursuit because you’ve done a lot with your life. So you left The Portland Clinic?

RUSTIN: And went to work for two other family practitioners in Portland where I was the secretary, bookkeeper, often the receptionist and a nurse’s-aid type of person. I stayed there for a number of years when I began to realize that the two physicians had a problem with deciding who was the boss. And I became the pawn. And when I was accused of favoring one doctor over the other, I simply said ‘ok you guys, I quit’. [laughs]. And I did. And within one hour of my having said that, I placed a call to the Medical Placement Bureau and the woman there said ‘how interesting, I just received a call from a Dr. Rustin, a Urologist, who desperately needs a secretary. Would you be interested in this job?” And we talked about it and I agreed that it sounded interesting. And she set up an interview and within two weeks, I started work at the office of Dr. Rustin and Dr. Collier.

Tarlow: And the plot thickens.

RUSTIN: Yes, but not for a long time. [laughter].

Tarlow: You worked there with Dr. Rustin for a long time?

RUSTIN: 12 years. Ten of those years… No, all 12 years were with Dr. Rustin and Dr. Collier. And after 12 years, with a lot of things happening in my life outside of that job, in those 12 years, I thought it was time to do something else with my life. I was now 39 years old and 40 was the number that frightened me as a single woman. So I decided to go to nursing school so that I could have a profession that would give me the credentials to get a job anywhere. I fancied living in Hawaii and that was very clear in my mind that that was what I would do after I got my nursing degree.

Tarlow: So, did you do a lot of traveling at this time while you were working for Arnold?

RUSTIN: The latter years, I did. I had gone to Europe in 1955 with my father. I didn’t go back to Europe, to Switzerland where my parents were born, again until 1970 but I did do that then. And in the intervening years, my travels included only Canada, Mexico, and Hawaii.

Tarlow: Which was enjoyable, something you wanted to do?

RUSTIN: Yes, yes. I began to get a taste for the rest of the world.

Tarlow: So, let’s talk a little bit about your relationship with Dr. Rustin because that changed considerably from being an employee to being a wife. And how did that come about? It’s a great story.

RUSTIN: During the entire 12 years, I had great respect for both of the physicians. But it was easy to see, even with my very limited experience, that Dr. Rustin had entirely different interests. And the things that he and his wife did sounded so impressive, and I wanted to do some of those things and by being the Rustin’s babysitter, I began to get close to Dr. Rustin’s, Jean. And, either she saw what my interests were or I expressed them, I don’t remember. All I know is that she took me under her wing and introduced me to things like the Oregon Symphony, good plays, and voluntarism. She took me to the Portland Adult Literacy Program where I became a tutor in that program for two years. That was my very first volunteer experience and I was hooked with the whole idea that this little farm girl had something to give to someone else and that was a real turning point in my life.

Tarlow: And what year was that?

RUSTIN: That would’ve been in about 1966 or ’67.

Tarlow: And then, unfortunately Jean died.

RUSTIN: Jean died in 1971.

Tarlow: She was very young.

RUSTIN: In those years, from 1967 until 1971, she had introduced me to a whole new world and, of course, Dr. Rustin was right out there on a daily basis in the office talking about things I could do; “why don’t you consider this”, “think about doing that”. I volunteered at Outside- In as a nurse even though I was not a nurse with nursing skills. And she even introduced me to the National Council of Jewish Women by asking me to set up a file system there in their office. I remember that very clearly and my going down to the Council Thrift Shop with her to help set up some kind of filing system there. Then, unfortunately, she died in 1971, but probably only six months prior to that, to her death, I had quit working for Rustin and Collier and entered Mt. Hood Community College’s Nursing Program. I did not like Nursing School. I was miserable the entire year I was there and at the end of that year, Jean had now been dead almost a year. And Arnold and I had begun a dating relationship. He had very clearly stated to me after Jean’s death, when we were going out to dinner or things like that, that he would never marry a woman who was not Jewish. And so I didn’t have hopes that he would ever marry me even though I knew I was embarked on a dangerous course of continuing a relationship with a man who said he would never marry me. He never said he would not marry ME. He said he would not marry a non-Jewish woman. But it did come to pass. He changed his mind.

Tarlow: It’s a good thing [laughter].

RUSTIN: And when we decided to get married, it was, it was just the most natural thing to do. We knew each other extremely well. However, I had a lot to learn; that working for a man was different than being married to a man. But there were no unpleasant surprises and, I was, contrary to what one thinks, for a very practical 39-year old woman, I went into this relationship, marriage, with no concerns about it working, the fact that we had two different religions in our backgrounds. It would just work. I just knew it.

Tarlow: Well, it took both of you, and it did work, and it’s worked for how many years?

RUSTIN: It will be 33 next month.

Tarlow: It’s worked.

RUSTIN: Yes. It’s worked very well.

Tarlow: So, now you’re married and your life significantly changes in a million ways and one of them was your conversion to Judaism. Let’s talk about that a little bit.

RUSTIN: Well, the most important change for me personally in the marriage, other than our relationship, was the fact that in doing so, I was estranging myself from my family. Some members of my family considered me as good as dead and those were the exact words my oldest sister used in writing to me about my marriage to Arnold. It mattered not that I had not converted to Judaism. It was the fact that I had taken a step that they felt took me away from any possibility of becoming a Baptized member of the church that I grew up in.

Tarlow: And the fact that you were married by Rabbi Rose, also?

RUSTIN: No …

Tarlow: That did not play any part in that?

RUSTIN: Ok, they never knew who married us. Some members of my family were willing to maintain that very superficial relationship and that has remained up to now and has become more cordial and closer than it was in the beginning. So with some members, I have a relatively good relationship. I never thought about a conversion. Arnold didn’t ask that of me. He said it doesn’t matter. And I didn’t really begin to get involved in Judaism as it was practiced by members of Congregation Beth Israel, the Reform Congregation until I had become more closely associated with Jewish women. (The tape seems to have been turned off at this point.)

Tarlow: Ok, we’re talking about conversion and what brought you to that particular point in your life.

RUSTIN: And I said I had not thought about it at that point. But since Jean Rustin had been active, was the president of the Portland section of NCJW, Arnold knew that this would be a good group of women and a good place for me to establish Jewish relationships so he called Joan Liebreich, who was president, and said ‘Rose needs Jewish people because she doesn’t have her own people any more’. And Joan took me to an NCJW meeting and I was, of course, absolutely awed by these woman and, of course, I wanted to be a part of what they were doing and tried to become worthy of their friendship because I saw them as such educated, smart, capable women. I wanted to be like that. And, and it happened. They, they let me in, [laughter] so to speak. And I began volunteering and the more I did, the more I liked it, and the more I, I pushed myself. They never did any thing to discourage me. I never had any idea that I would be as good as they were but for whatever reason, they allowed me to be a part of that and that is what convinced me that I needed and wanted to become a real Jew.

Tarlow: So we are back at the NCJW who embraced you like crazy, because I was one of those so I know. And that inspired you to do some other things. So tell us about that.

RUSTIN: Well, I continued volunteering for NCJW and one of the first jobs I had got me involved in a women’s organization, a coalition of other religious groups and some non-religious groups, but different ethnic groups called WICS; Women In Community Service. And very shortly after, I was the volunteer representing the Portland, Oregon section of WICS. I was fortunate to be elected to the national board of WICS which gave me the opportunity to work with other women’s groups and gave me a lot of confidence about my own capabilities. But the other thing it did was make me so proud of being a Jewish-organization representative that it just boosted my desire to be a part of this group. However, before I got to the point of being really ready to make the choice of Judaism as my religion and I was taking classes and reading books and study, I was elected the president of the Portland section as a non-Jew, which was, I think, quite a …

Tarlow: A tribute.

RUSTIN: A tribute, to both of us; to me and to the organization. And during my presidency, I took the step after great encouragement by Rabbi Rose. I can still hear him saying to me, because we were meeting once a week, “Rose, you’re ready. You are absolutely ready. Don’t worry that you have to give up your own cultural ethnic background. You don’t.” That was the issue that I was hung up on for a long time. When that was resolved, I made the step of becoming a Jew. I later studied long enough to have my Bat Mitzvah with a group of other people and, have ever since felt myself a Jew, no question.

Tarlow: Let’s say that Rabbi Rose still is the rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Portland where you were converted and later went on to be the president of the Congregation. So, let’s go on from your being the president of NCJW to your conversion and let’s go two ways; your national involvement with NCJW and your involvement with Temple Beth Israel.

Tarlow: They go together.

RUSTIN: They go together but not, but sequentially. After being the president of the Portland section of NCJW, I was elected to the National Board and for four years, I had literally a job with NCJW as a trouble shooter, trainer, leadership-development person for the Western District of NCJW which, which not only gave me training, but allowed me to do training which only further enhanced my feeling that I could do more than what I had been doing, or thought I could ever do. Those four years, during which time I was becoming involved in Congregation Beth Israel were training years given the experience that organization allowed me to have. When I finished those four years, I was now pretty active on the board at Beth Israel, having started with chairing an outreach program for which I was well suited, having been both a Protestant Christian, and now a Jew. While I was on the board, with Arnold’s encouragement and, and a nagging feeling that the one element in my life that was truly missing was more education. I began pursuit of a Bachelors Degree in the Humanities at Marylhurst College. I completed that degree precisely the month I was elected the president of Congregation Beth Israel. The timing couldn’t have been better. And I remember very clearly, two years later, in my outgoing speech to the congregation of Beth Israel. I made the statement that when I took the presidency of Beth Israel, I had just finished four years of college education and that I saw the two years as president of Beth Israel as being the completion of a degree in a higher education. And I truly have felt that way. At that point, I thought, “I guess I can take it easy for a while.” I really slowed down in my volunteer activity, keeping very good friends from both the NCJW experience and the Beth Israel experience and being happily married, having a good life with the normal ups and downs, health problems that any couple would have but I can’t ask for anything more than what I have now.

Tarlow: It’s wonderful. I mean, you should be so proud of yourself, to have the initiative and the backing that you had from your family to go ahead with all of this and how much you added. But this is not my interview. This is yours. You are still involved in the community. You still have your fingers in, even though you’re retired from all this big stuff. You are still, what are you doing today, besides cooking?

RUSTIN: It’s interesting that I’m back at NCJW doing a project that I have called the ‘NCJW Archive Project’ because I guess when one reaches the age that I am now, which is approaching 73, you begin to have an affinity for nostalgia and the maintenance of, and keeping, not in my home, I’m not a keeper of old things but I understand the necessity in historic ways of keeping old things so that I chose to make my volunteer involvement at this point the saving, if you will, of the NCJW archives.

Tarlow: And the Neighborhood House information as well?

RUSTIN: Yes.

Tarlow: And where is that going to go?

RUSTIN: It’s going to go to the OJM [Oregon Jewish Museum], where I have an ultimate goal, and Judy Margles, the Director, and Anne Prahl, the Curator, know, because I’ve spoken about it so often that I hope to have one day an exhibit of NCJW and Neighborhood House, using the materials that are being given.

Tarlow: What else? What else are you doing with your time?

RUSTIN: I do a little bit of work through Congregation Beth Israel Sisterhood. A couple of committees.

Tarlow: What are they?

RUSTIN: A little bit of community service work such as serving meals at the Goose Hollow Shelter, six or seven months out of the year with other NCJW and Beth Israel friends. But I’m not really doing much else other than the social things I do with my friends.

Tarlow: How do you relax? Tell us what you do for fun, not that these other projects aren’t fun.

RUSTIN: Well, I’ve been a reader since I was a little girl and that, as time allows, that interest in reading just progresses and I read more and more. I’m also, since I was a little girl, been a word-puzzle person. It’s very important that I do the New York Times crossword puzzle every day and towards the end of the week, it takes a little more of my time each day because they get more difficult and Sharon can see I’m only a third of the way through this Thursday puzzle. I like puzzles of all kinds. I get a great deal of pleasure out of the exercise program I’m in at the YMCA where I, of course, find other book lovers and we have our own little lending library book group there. Jigsaw puzzles are also my meditation vehicles. Sharon, you know mostly what I’m doing.

Tarlow: [laughs] I know you like to go to plays.

RUSTIN: Yes, and I like Chamber Music Northwest in the summer.

Tarlow: Right. Book groups.

RUSTIN: Book groups, two of them; one at Beth Israel and one, our NCJW-related Shabbat group women.

Tarlow: So let’s talk about the Shabbat group a little bit, of which you are very much a part.

RUSTIN: Well, the closest group of women friends are those with whom I became acquainted when I joined NCJW back in 1973 and these women, there are eight of us

Tarlow: How about naming the eight women? And there are some men too.

RUSTIN: It is these women who have been together all of these years who are the core of the Shabbat group. It began with Joan Liebreich, Carol Chestler, Sharon Tarlow, Shirley Rackner, Elaine Weinstein, Cookie Yoelin, who unfortunately passed away about five years ago, Evelyn Maizels, Berta Delman. Except for Cookie now, the rest of us have been going together for so many years, we finally decided, it will be 20 years ago, that we needed to have a regular meeting time with our husbands and that we would do it on a Friday evening when we could celebrate Shabbat in one another’s homes and we have been doing this these past, I’m sure it’s 20 years, without stopping and it, we have a bond which I think is exceptionally strong and maybe unique. But it is one of these truly warming experiences, the way we support each other in good times and celebrating the good times, supporting each other when times are not good for one or the other. I can’t explain it, any more than say it is one of the warmest, loveliest experiences one could have.

Tarlow: [can’t hear] When you think about your life and all the things you’ve done, which are so many. I hope we’ve mentioned all of them. What do you think is your favorite accomplishment?

RUSTIN: If I judge it by my emotional reaction or experience, there is no question but how I felt when I was awarded my Bachelor Degree at age 62. That was the happiest time of my life. While it may not be the thing that was the greatest accomplishment, of all the things I have done, it was the one thing I thought I would never ever be able to do. And that may sound very strange that I could be the president of NCJW, serve on the national board of two organizations, somehow being able to graduate a university with a degree was something I never thought I could do. But you have to put this into the context of this girl who finished school when she was 14 years old, who never stepped foot into a university of higher education until she was 57 years old.

Tarlow: Right. It’s a wonderful accomplishment. And out of that education (I equate it with your education), came a book. And we didn’t even talk about your book.

RUSTIN: No.

Tarlow: Well, we better talk about it a little bit.

RUSTIN: When I entered Marylhurst, I so blithely said to my counselor, “I just know I want a degree in the Humanities and I don’t know what it’s going to take but I don’t want to study anything that’s going to lead me to a job or anything like that. I just want to study, I want to learn about everything”. And he said ‘Well, that’s fine. But to get a degree in the Humanities, you have to choose one of the arts. You have a choice between music, painting, all the fine-arts things, and there were several others. But lastly, he said ‘creative writing’. And as he ran down this list, I kept thinking “I don’t want to do that, I’m not interested in this”. And so I said “well, of all the things you’ve named, maybe I could do creative writing”. I was good with English. I knew I could speak. I didn’t speak well, I thought, particularly. But I liked to talk. And in fact, he said ‘Rose, if you write just half as well as you talk, this will be the thing for you’. And so I had to have as part of my major, a thesis, if you will, which had a different name at that time. I embarked upon creative writing classes all the five years that I was at Marylhurst. Lots of literature. I didn’t need to take any English. I challenged all the English courses but I began writing and it was Arnold who gave me the idea that my writing subject should be my dad’s family in Switzerland. It was an unusual family. There was an unusual amount of documented material about the family and it was a natural choice. So I began writing the story of 13 generations of my father’s family in Switzerland.

Tarlow: And their names?

RUSTIN: The name was von Flue and it began with the ancestor we called Bruder Klaus, Nicholas. He was born in 1417, and ended with the death of my father in 1983. And the story was about the 13 men from Bruder Klaus to Kapfli Walter, which was my father’s nickname.

Tarlow: Which was a huge accomplishment illustrated by?

RUSTIN: Arnold’s photographs and self published with the help of Kinko’s [laughter]. Not a leather-bound book.

Tarlow: But it was a book.

RUSTIN: It was a story, which I was happy that each of my 40 nieces and nephews and their children purchased [laughter] to help me defray the cost of publishing, self-publishing the book. It was a great experience and something that pleased me no end.

Tarlow: A wonderful accomplishment. You have many accomplishments. So I guess we’ll end with the future; what do you see the future holding for you?

RUSTIN: A continuing maintenance of reasonably good health by all things that we know will help me in that direction; exercise, good times, food, and relaxation. And I feel that I am at a place that I can do all of these things and I just see myself continuing with the support of friends and family for a good number of years.

Tarlow: I guess we can say ‘life is good’.

RUSTIN: Life is VERY good right now.

Tarlow: Good. Thank you Rose. This has been just wonderful. We’re going to enjoy listening to it.