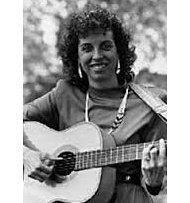

Margie Rosenthal

b. 1947

Margie Rosenthal was born Margie Kieffer in 1947 in Waterloo, Iowa. Her father was in the clothing business and ran several stores in Iowa and Minneapolis before moving the family to Southern California, where Margie and her brother Max (Mac) spent their childhoods. Margie became interested in Jewish music at Reform Camp Saratoga (later named Camp Swig) and in the Reform movement’s youth organization National Federation of Temple Youth. She attended college at UCLA, finishing her degree in English at Berkeley and then graduate school in special education at San Francisco State. Throughout high school and college, Margie worked at Jewish camps. It was at Camp Chai, in northern California where she met her husband Elden in the summer of 1964. They married in 1969 and lived at Stanford until Elden finished law school in 1972 before moving to Oregon, where Elden had an aunt and uncle, Edith and Paul Lavender.

Margie began teaching music at the religious school at Congregation Beth Israel and later taught visually impaired children in the Portland public schools. They had two daughters, Rachel in 1975 and Debra in 1978. Margie continued to work with children with special educational needs. She co-founded the Portland Reading Foundation, which provides professionally trained special education tutors. She also continued singing and recording Jewish music in Portland and throughout the county. She has won numerous national awards for her CDs of lullabies and Jewish children’s songs recorded with Ilene Safyan.

In 1978 Margie attended the first meeting of the newly forming congregation Havurah Shalom and she and Elden immediately became involved in the growth of that community. Each served as president of the congregation. Margie organized and led the first High Holiday services the congregation offered in 1979 and went on to be the musical director, and, along with Ilene Safyan, continued teaching children and leading adults in song for 30+ years.

Interview(S):

Margie Rosenthal - 2015

Interviewer: Joan Weil

Date: May 18, 2015

Transcribed By: Carol Chestler

Weil: Can you give me your full name, date of birth, and where you were born?

ROSENTHAL: My legal name is Marjorie K. Rosenthal and I was born in Waterloo, Iowa in 1947.

Weil: Can you describe your household as you were growing up?

ROSENTHAL: My father worked, my mother was a homemaker until I was in junior high or high school, when she started to work. I had an older brother, and my only surviving grandparent lived nearby. So that was our nuclear family.

Weil: Where were your grandparents from?

ROSENTHAL: My grandparents on my father’s side: my grandmother Edith was from a German-Jewish background and had come to the United States around the turn of the century, I believe. My grandfather, Charles Kieffer, came from Kominetz-Litovsk, a small village in the Pale of Settlement. But he came to the United States around 1905. His father Shlomo came earlier and sent for the family. So my grandfather had been in the US for several years when they married. My grandmother and grandfather on my mother’s side were both from the Pale. My grandfather came as a 13-year-old with his older brothers. And my grandmother Sarah was already in the United States. She had been here since the turn of the century too. They were all pretty well established in Minneapolis and St Paul.

Weil: But as you were growing up three of your grandparents had already died.

ROSENTHAL: Yes. Two of them were deceased before I was born and my father’s father died when I was two or three. So I didn’t really know him. I only knew my mother’s mother.

Weil: You said your father worked. What did he do?

ROSENTHAL: My father was in the clothing business. His father had started a small men’s clothing store in downtown Minneapolis called Kieffer Clothing. And after the war my father and his brothers all worked in the store. And then, my father wanted to be on his own and ended up leaving there and we went to Southern California. There he managed men’s clothing stores and then ended up being the president of a national company of men’s clothing stores.

Weil: But you were born in Iowa.

ROSENTHAL: I was born in Waterloo, Iowa. At that time it was right after the war and my dad was working in a clothing store in Waterloo. Then we went back and lived in Minneapolis for a while. We also lived in Galesburg, Illinois for a while – I don’t remember why – In 1955 we moved to California.

Weil: So you considered your growing-up years in California. Where in California?

ROSENTHAL: Southern California, east of Los Angeles, in San Bernardino.

Weil: And your father was still in the clothing business at that point?

ROSENTHAL: Yes

Weil: Can you tell me about your religious background as you were growing up?

ROSENTHAL: Sure. In Minneapolis I don’t really remember anything about religious school. I know we belonged to a synagogue. My dad grew up belonging to the Conservative synagogue in Minneapolis and my mother grew up belonging to the Conservative synagogue across the river in St. Paul. I believe that we belonged, after they were married, to the Minneapolis synagogue. But I don’t remember it. I’m sure I went to religious school before we moved. I was in second grade when we moved. But I do remember observing holidays with big family gatherings because my father had three brothers who all lived in the Minneapolis area. My mom only had one sister, who also lived there. But in my Grandma Sarah Padwal’s family there were seven aunts and uncles. So we were always at somebody’s house with a whole lot of cousins for all the holidays.

Weil: So you remember big Passover Seders and things like that.

ROSENTHAL: Right. Then when we moved to California we had some relatives in California that we celebrated with. But in San Bernardino it was just our family and we were active members of the Jewish Community. We went to Friday night services regularly and my parents were very active in the small synagogue in San Bernardino, Temple Emanu El. And it was an unusual synagogue in that it was the only synagogue in town. And it really was the only synagogue within probably a 30-mile radius. So very early in the morning the services were Orthodox and then about 10:00 they sort of became kind of a Conservative shul and by 11:00 we were using the Union prayer books. So it was a real mix of people.

Weil: And you had one rabbi.

ROSENTHAL: One rabbi.

Weil And how was that rabbi affiliated, do you know?

ROSENTHAL: The rabbi who was there when we moved there was kind of like Rabbi Stampfer. He’d been there for a long time. He was an older man, wonderful man. I don’t know what his affiliation was.

Weil: Do you remember his name?

ROSENTHAL: Yes. Rabbi Norman Feldheim. He was revered by everybody. And I assume he had sort of a diverse training. But when he retired we hired somebody from the Reform Movement, Rabbi Cohen, Hillel Cohen, who was there until he retired.

Weil: And he was still doing the three affiliations services?

ROSENTHAL: Yes, when I was there he was. Eventually there were synagogues built in the surrounding communities. When I was a kid everybody came. They came from Rialto, Riverside, and Fontana and all the little communities that were around. That’s how I remember it anyway.

Weil: Did they do bar and bat Mitzvahs there?

ROSENTHAL: Yes.

Weil: Were you bat mitzvah?

ROSENTHAL: No. Girls were not bat mitzvah that I knew of. I didn’t have a single friend who was bat mitzvah. My brother was bar mitzvah. Girls didn’t learn Hebrew; we went to religious school on Sundays. But the girls didn’t learn Hebrew at all.

Weil: Did you have a camp experience?

ROSENTHAL: I did. I did not have a camp experience as a camper per se. My parents couldn’t afford to send me to Jewish camp. But when I was in high school I got a scholarship to go to Camp Saratoga, which is now called Swig, in northern California. So as a sophomore in high school I went for two weeks to the Reform Jewish camp. In addition to that I was active in our synagogue youth group. We had retreats on a regular basis in the Los Angeles area so I knew Jewish kids all across Los Angeles and West Covina and San Bernardino and Palm Springs. I had friends in these other communities. So there was this very active Reform Jewish movement and experience.

Weil: It was Reform, so that’s part of the NFTY organization?

ROSENTHAL: Exactly. It was called SCFTY – Southern California Federation of Temple Youth. So we had a Junior SCFTY. Ours was called something else because it was part of the synagogue. But whatever it was called, there was a junior group for the junior high school kids and then there was a high school group and I ended up being the president of either one or both in my tenure there. I was very active in that. My mother was very involved in Hadassah and in Sisterhood at the synagogue. My father was on the board of the temple and was president for a while. So we were very involved there.

Weil And your brother too?

ROSENTHAL: Yes, my brother, who was a very quiet person, participated in the youth group. My brother had a beautiful singing voice and from the time he was bar mitzvah to the time he went off to college he often helped to lead services.

Weil: What was your brother’s name?

ROSENTHAL: Mac Kieffer.

Weil Mac.

ROSENTHAL: Max, but we called him Mac.

Weil: Okay. When did you start playing guitar and singing?

ROSENTHAL: I think it was the Camp Saratoga summer that inspired me because at that time – this was before Debbie Friedman – there were these three song leaders at camp who were amazingly dynamic people. One of them was a woman. A woman doing Jewish music was something new. I do not think she went on to be a rabbi because that was 1962 or something. The other two men became rabbis in the Reform movement. The camp was a lot about music, to me anyway; that was what stuck with me. My brother played guitar a little bit so when I came home from camp I think is when I started being interested in it. I don’t think I really played until my brother went away to Israel on some summer program that he got a scholarship for and he left his guitar at home. So then I started picking it up and playing it.

Weil: So the community that you grew up in, the high school that you went to, were there many Jewish kids in the high school?

ROSENTHAL: No. I wouldn’t say there were more than 5%. But I knew them all. It was a huge high school, huge; it was the last year before they built the new high school. The Jewish kids all belonged to the same synagogue. Now there may have been Jewish kids that were unaffiliated but I didn’t know them particularly.

Weil: Okay. So let’s go on to college. Where did you go to college?

ROSENTHAL: I went to UCLA undergrad. That was my first exposure to being somewhere where there were a lot of Jewish people. Because San Bernardino wasn’t – there weren’t very many Jewish people in the whole town. I was at UCLA for 3 1/2 years and I did my last semester at UC Berkeley and then I went to grad school at San Francisco State.

Weil: When did you meet Elden?

ROSENTHAL: I met Elden at camp. From the time I was a junior in high school I worked at Jewish summer camps for 5 or 6 summers in a row. I met Elden at a very odd camp above Palm Springs called Camp Chai that I believe was affiliated with the Conservative movement. The rabbis connected to the camp were from the Conservative movement. It was kind of an offbeat camp. The people who didn’t send their kids to Hess Kramer, which was “the camp,” in southern California to go to, sent their kids to this camp. So I worked at that camp —

Weil: When you say you worked, what were you doing?

ROSENTHAL: I was a counselor and I led music. Elden’s sister was my junior counselor so she was a counselor in training. Elden’s dad was a conservative rabbi in southern California, and he would come up to the camp to do Friday night Services. So I knew him before I knew Elden. Elden came up the summer of 1964. He had gone on a trip for the summer and come back and somebody had to leave camp, was ill or something, and Elden took his place. So that’s where I first met him. He was a debater in high school and my brother was a debater in high school. So they knew each other. Then I re-met him at UCLA.

Weil: What was your degree in?

ROSENTHAL: Undergrad was English and in grad school I got a degree in special education.

Weil: What did you do after college?

ROSENTHAL: I got married and we moved to Oregon. We got married in 1969, and Elden was in law school so we lived at Stanford for the first 3 years we were married, and I continued to do music for Jewish camps and religious schools in the Bay Area. Then we moved to Oregon when Elden graduated.

Weil: And what bought you to Oregon? Was it a job?

ROSENTHAL: No, Elden had an aunt and uncle who lived here. Elden had a fond memory of Portland. We wanted a small big city. Elden and I are both outdoors types so Oregon offered a lot of that. Although we both liked northern California, it was too expensive. So we came up here. We were part of the California exodus of the early 1970’s.

Weil: So what year did you move to Portland?

ROSENTHAL: We moved here in ’72.

Weil: And your aunt and uncle’s names?

ROSENTHAL: Edith and Paul Lavender. They were very active in the Jewish community. Edith was Elden’s father’s sister. They were very active at Beth Israel. I got a job right away at Beth Israel teaching music for the religious school, so that would be sometime in ’72.

Weil: So then you had children?

ROSENTHAL: Yes!

Weil: Tell me about your children.

ROSENTHAL: I have two children. Rachel was born in 1975 and Debra was born in 1978. At that time, I was teaching visually handicapped children for the Portland public schools. And then working on Sundays at Beth Israel doing music. I was also helping with music at some special services at Beth Israel.

Weil: So the girls had their early education religiously at Beth Israel?

ROSENTHAL: No. Because by the time Debra was born, Debra was a month old when we had our first Havurah meeting.

Weil: All right, let’s talk about Havurah. What brought you to Havurah? What do you remember about the early meetings of Havurah?

ROSENTHAL: Well the first meeting I remember that Debra was a month old because I was holding her and nursing her. What I think I remember best is that we had belonged to Beth Israel for 5 years. Although I was working there, and we were very close friends with Rabbi Alan Berg, the assistant Rabbi, we really didn’t have any connections to the families at Beth Israel, because our kids were too young and in those days, people didn’t bring their kids to services.

So I didn’t really know any young families. When I went to the first Havurah meeting there were all these people there with kids my kids’ age. That was really exciting because we hadn’t connected with very many people. I was friendly with a couple of people that I had met working at the JCC camp in the old JCC building. That’s where I met Mari Livingston and Lou. But other than that, we really didn’t have very many Jewish friends.

Weil: How did you hear about that first meeting?

ROSENTHAL: I’m not absolutely sure but I think at the time Mari Livingston lived near Lesley [Isenstein] and they had some sort of a summer thing where we would order vegetables and fresh fruit and so my name was on a list of people that Lesley knew but I didn’t really know Lesley. Somehow I got invited to the meeting. That’s all I know.

Weil: Do you remember anything about the meeting?

ROSENTHAL: Yes. I remember that what people were talking about was that they wanted something Jewish to belong to that they could do with their young families that was active and fun, that was camp-like. They wanted a social gathering that was Jewish. That’s basically what I remember.

Weil: Where did it go from there?

ROSENTHAL: The group agreed (I don’t know whether they agreed at that meeting but certainly within a very short amount of time) that we’d try to get together once a month or every other month. We started off by organizing a summer picnic in the park. The first time we met was June, because Debra was a month old. So I know that it was June of 1978. Then we probably planned a picnic for July and it rained. That was pretty typical. And we ended up at your house.

Weil: Right, I remember that.

ROSENTHAL: And you had children, one child that was exactly Rachel’s age so that was a quick connection there. And I think that from the first gathering, it might not have been at the meeting, but from the first gathering it was clear that this was a fun group of folks. Everybody was committed to thinking about how to celebrate holidays. We weren’t looking at being a congregation. We were looking at being a Jewish social club of some sort or other. Within that group, there were people who belonged to other synagogues as we did, as we belonged to Beth Israel. There were people who were leaders at Neveh Shalom, there weren’t any Orthodox as I recall. But there were people who belonged to other shuls, who came for the social aspect.

Weil: What do you remember of the early meetings or services that you had in the first year?

ROSENTHAL: I always had my guitar and would lead some singing. Well I don’t remember how we decided to organize the first High Holiday service. That September of ‘78, we decided to do a service on the afternoon of Yom Kippur. We didn’t think we could take on any more than that but we decided to do that.

Weil: And where was that?

ROSENTHAL: At the old Neighborhood House. I don’t remember exactly whose idea it was to approach the Neighborhood House about having the meeting there. But it seemed like the right place to be because it was a Jewish building. We didn’t have the chutzpah then to ask the JCC or anybody else to have the meeting there. What I remember about it is that I had to give up [doing services with] Rabbi Berg at Beth Israel. I used to do an afternoon service, sort of alternative service at Beth Israel.

Weil: Just for High Holidays?

ROSENTHAL: Well he and I did a lot of alternative services at Beth Israel. But there was always controversy about these alternative services. We had to do it in a different room, it couldn’t be in the sanctuary because you couldn’t have the guitar on the bima in those days. We had what we called the Miller Room Service. Before they added the addition at Beth Israel it was in their little Miller Room. It started out very small. By the time we started Havurah [by 1978], it was a going concern, the Miller Room service. It was a lot of music and sort of interesting readings and there were a lot of people that came. Rabbi Berg chose sermon topics that were cutting edge. But there was a growing discomfort at Beth Israel about having an alternative service and about pulling people from the main service. So anyway I said that I knew what Rabbi Berg and I had done from this alternative Yom Kippur service. Elden had the background of having a father who was a rabbi, so he volunteered to help lead the service. Priscilla Kostiner volunteered to be involved in it. If I recall correctly Wendy Liebreich was also involved in organizing, or it could have been Howard. I’m kind of picturing the people who led that service. I did the music. I talked to Rabbi Berg; he helped me figure out what to do. I think Gene Borkan was also involved in music for that service. I don’t remember how many people showed up. Maybe you remember. We had a full house. There were people that had met through our early meetings, but there were also all kinds of people who just sort of appeared. Unaffiliated people, I don’t know how they all got there.

Weil: There were no tickets, no money to come; it was just anybody who wanted to come.

ROSENTHAL: Anybody who wanted to come. Since I was involved in the organizing of the service, somebody else must have been involved in how we got the word out because I don’t have any recollection of that. Then I think it was from that experience that we started talking about creating a synagogue. That was something that was different from a social gathering. Within a few months we started doing a Friday night at the Neighborhood House on a regular basis, maybe once a month or every other month. I don’t exactly remember. We did a potluck dinner and then a service. There were loads of young children, lots of singing and clapping.

Weil: What were those services like?

ROSENTHAL: Those services were like the Miller Room services [laughs]. Different people came forward to lead the services. I usually did the music, because I don’t think there was anybody else who knew the music yet, then. And I didn’t really know so much music but I would ask around until I could find what was good to do. I remember that the services always had kids involved. Whatever family was involved in leading the service, their children, no matter how old they were [laughs], if they were old enough to stand up and be in front of the group, they were there. There was a lot of clapping and singing and then an Oneg Shabbat. That’s how I remember it. People sitting on the floor in a semi-circle. We didn’t have any kind of prayer book so we would mimeograph services. Even then, it was a lot of work, but everybody seemed to enjoy doing the work.

Weil: Do you remember any others? Were there other holiday celebrations during that year that you might remember?

ROSENTHAL: I get the years confused. I believe we celebrated Hanukkah together. I don’t remember Sukkot that year. I just remember the High Holidays. I think we got together once a month, sometimes it was to celebrate a holiday and sometimes it was just for a service, a Friday night service. Later we did do Sukkot too.

Weil: When did Alan Berg get involved?

ROSENTHAL: In the spring of 1979 Alan decided to take a sabbatical from Beth Israel. I think he was thinking that he was going to write, so he was going to take some time off. We were very close friends. He and his ex-wife and Elden and I were very, very close friends. So we said to him, “Would you help us with our new group?” Initially he was just giving us ideas. But at some point or other we went from casually having Friday nights to deciding we were maybe going to be a congregation. Now whether that coalesced around Alan or whether it coalesced a little earlier and then Alan fed into that, I cannot remember that. But there were people who were part of our group, our regular Friday nights, who wanted to be part of a synagogue. And there were people who didn’t. There was a real split there. Sometime between May or June of ‘79 and the fall of ‘79 Alan agreed to join us. We agreed to raise some money to pay him to give us some of his time. We had several meetings and events over the summer, I recall that summer, picnics in the park and things when it didn’t rain. And then in the fall of ‘79 we had a full complement of High Holiday Services. We had Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services and Alan led those services. He brought in Aryeh Hirschfeld who, was at that time not yet a rabbi but who had kind of replaced me at Beth Israel. He was doing music at Beth Israel and that’s how Alan knew him. Aryeh agreed to help us. For me, he was a wonderful, charismatic teacher, because I knew very little liturgical music and Aryeh knew a lot and wrote his own. He led the [music for the] service. Alan led the liturgy parts of the service. But there were also members of the congregation who were involved in the leading of those services.

Weil: What was Alan’s role when he was working for Havurah?

ROSENTHAL: I think that we were looking for…. The early Havurah families, knew how to do the social part. And we knew how to have fun. And we knew how to cook. [laughs] But we didn’t know the adult education pieces that were really important to us. We wanted some adult learning too. I think what Alan brought was a level of intellectual Judaism, not only the spiritual part, but he brought us things to study, things to think about. He was a catalyst for adult education and kind of thinking outside the box of just having the prayer book in front of you and going through the service.

Weil: So he was leading services? And he was doing an educational program as well?

ROSENTHAL: I can’t remember for sure if Alan was necessarily leading all the Friday night services. I think the families were continuing to do that. But Alan was like an advisor. If I were leading a service and I wanted some ideas, I’d ask him. I think he may have led pieces of some services. But I don’t think he came to all of them because I think he was busy. I think his wife was not thrilled about this process of him taking a sabbatical and then working while he was taking a sabbatical. [laughs] But he helped us with social action ideas, he helped us with education ideas. That’s my recollection.

Weil: How long was he with Havurah?

ROSENTHAL: He did that from the fall or the summer of ’79 through the winter and spring of’80. Sometime that spring he decided to go back to Beth Israel. His sabbatical was up. We hoped maybe he wouldn’t want to go back to Beth Israel. I think both for his financial needs and his rabbinic career it was better for him to go back to Beth Israel than to be part of this sort of renegade group.

Weil: How did Havurah make that transition without a rabbi?

ROSENTHAL: Well, by then we had enough lay leadership, enough people had led services, knew where to get the materials and that kind of thing. We just decided to keep it going with families volunteering. By then we had formed a religious school.

Weil: Where were we meeting?

ROSENTHAL: We were meeting at a wonderful place in southwest Portland, the West Hills Unitarian Fellowship. That was just the perfect spot for us because it was woodsy and warm and inviting. They were thrilled to have us rent space from them. It was a wonderful relationship. We had our Friday night services there. At that time we were just meeting once a month, I think, maybe every other week. I don’t remember for sure. We had holidays there. We had Saturday morning Torah study that either Alan led when he was there, and then Aryeh took over and we paid him to lead our Saturday morning Torah study, adult Torah study. And then the religious school was on Saturday afternoon. That was another one of my big involvements with Havurah. Mari Livingston and Mimi Epstein and I, with the help of a lot of other people, put the religious school together. What we wanted was a religious school that was educational and fun. We knew we didn’t have the resources or the inclination really to do what you would consider to be a formal religious school. We decided that the parents would teach. I had gone to religious school (as everybody else had) where your parents dropped you off. My parents would go and play golf. We didn’t want that; we wanted something different. We wanted something where the parents were actively involved in the school and the parents were learning while the kids were learning, or with the kids. We met on the afternoons of Shabbat, because it was clear to us that between soccer and birthday parties and whatever else that all took place on Saturdays we couldn’t do it in the morning or the middle of the day. People didn’t want to do it on Sunday mornings. They wanted to do it on Shabbat. That’s what we did. We started each session with music and ended with music and with Havdalah. It was a lot of fun.

Weil: How were decisions made in the congregation?

ROSENTHAL: By 1979 we had formed a steering committee. Elden was the first president and Lesley Isenstein was the second, the vice president. And we had some elected officers. I think we made decisions the way any non-profit or synagogue makes decisions, with a board of people that worked things out. We assessed ourselves a very low amount of dues. We agreed if people couldn’t afford to pay the dues they would have some sort of scholarship. We did all that very early. The other thing we did early is we decided we needed to have a cemetery. And that was very early – if we were going to be a congregation. And there was a lot of back and forth about whether or not we really could be a new congregation in town. Whether we needed a new congregation in town at all. There were people who were, as I said before, who were totally opposed to it and didn’t want to pay dues, and didn’t want to have anything to do with anything that they would consider to be organized religion. But I think there were enough of us who felt strongly that there was something missing in Portland, in the organized synagogues.

Weil: What were the organized synagogues at that time?

ROSENTHAL: There was Beth Israel, which was Reform, very large Reform synagogue; Neveh Shalom, again large, a Conservative synagogue; Shaarie Torah, a large Orthodox synagogue. There was, on the east side, Tifereth Israel, which was a slowly dying off congregation that I believe was Conservative, but I’m not positive. There was the Sephardic shul, Ahavath Achim. That was it I believe. We were the first new synagogue in fifty years or something like that in Portland. I think initially we didn’t really know whether this was going to be a five-year project or a ten-year project, or whatever. I think we had some goals but we hadn’t sat down and made a strategic plan and all those things that we do now. But I think we were committed to celebrating being Jewish together as families. We were committed to adult education, to some sort of education for the kids. We were really committed to the idea that everyone who joined would participate in some way. Whether you had a strong Judaic background or you didn’t we figured there were ways to learn what you needed to. We welcomed intermarried families. Early on I think every family was expected to lead a service over the course of a year or two. We helped each other.

Weil: How long were we at the Unitarian Fellowship?

ROSENTHAL: I can look that up.

Weil: Oh that’s all right if you don’t remember.

ROSENTHAL: We were there for probably five years, I would think.

Weil: And then what happened?

ROSENTHAL: I don’t remember whether they had a conflict with our use of the space, whether their community needed the space or whether it was a good idea to move to the JCC. At some point we started negotiating with the Jewish Community Center, because here was this wonderful building that nobody was using on Friday nights and Saturdays. We approached the staff at the JCC about renting space.

Weil: Were you involved personally with that?

ROSENTHAL: No not at that point I wasn’t. I don’t think so. My recollection is that the staff of the JCC and the board of the JCC was willing to let us rent space, which we started doing in whatever year it was. It was somewhere in the early ‘80s, maybe 83, 84. So we used the foyer at the JCC for our Friday night services and we had access to the classrooms for our religious school. For high holidays we met in the big auditorium. That went on for a number of years. During that entire time there was an objection from members of the Board of Rabbis that we were using this Jewish space and didn’t have our own building. So there was a constant sort of back and forth on that.

Weil: So at some point the JCC let us know that we should be looking somewhere else?

ROSENTHAL: Right, so in the early ‘90s, I don’t remember exactly what year. Somewhere in the late ‘80s we found out the JCC was going to do an addition. Two or three of us agreed to volunteer on the JCC board and I was one of those [laughs] because I was working at the JCC. I was doing music at the JCC already. I was known there. I volunteered to be on the board and a couple of other people from Havurah who were active at the JCC volunteered to be on the board. Sitting on the board we were able to negotiate use of the new space they were building. So for the first few years we were in the foyer, which was not in any way conducive [laughs] to a Friday night service. It worked for us but it wasn’t a lovely space. We knew they were building a chapel. We were able to use the chapel once it was finished. Sometime in ‘92 or ‘93 the powers that be at the JCC were kind of told by the Board of Rabbis that we should not be able to rent that space anymore, that we couldn’t have this long-term rental concept going on. That was when we started the whole discussion of whether or not we wanted a building.

Weil: Okay. Before we go on to that I think we skipped over a few things. One of them is when you met Ilene, when you started singing together.

ROSENTHAL: Ah, yes. Ilene Safyan and Mark Rosenberg moved to Portland sometime the fall of 1979. Ilene had some connection from Pittsburgh to Berta Delman. I don’t exactly remember what the connection was. And when they met she told Berta that she was interested in Jewish music and whatever. Berta said to her, “Well you ought to find out about this Havurah.” Because Berta and Jay were involved. I don’t think they came to a service, because I’m sure Ilene at that time would have said to herself, “Hmm. I don’t know about this.” Ilene comes from a much more Conservative background. this was probably some weird group. But somebody else that met Ilene, Ann Adler, invited Ilene over to the house and invited me over to meet her, because she thought we had some things in common. It was a very funny meeting because I arrived with Rachel who was four at the time and Debra who was not yet two, my Pack’nPlay, and all my junk and whatever to this woman’s house. I had met this woman before but I didn’t know her at all. Ilene was a young newly married person with no kids, and here comes this lady with all her paraphernalia and whatever. She and I started talking and we just hit if off immediately. To tell you the honest to goodness truth I don’t know that I ever saw the Ann who invited us again [both laugh]. I don’t know that Ilene ever saw her again. Maybe she came to Havurah, but I do not remember. I hope I thanked her. I know where her house was. From then on we were just friends. They didn’t join Havurah right away. I know that they came to the 1979 High Holiday service that Rabbi Berg led. I know that they thought it was pretty odd, but by the fall of 1980, I believe they joined. Ilene, unlike me, actually had a strong Judaic background. She could read Hebrew; she knew the prayers. That really made a lot of difference. She and I could learn together and she had much more background.

Weil: So that’s when you started singing together?

ROSENTHAL: Well, we sang together for things for Havurah. Oh, I was teaching music at – yeah, let’s see…. In 1980 Elden took a sabbatical and I gave up my teaching job. We were gone for three months. Rabbi Berg and his wife actually lived in our house and had their first child at our house. We went away and when I came back I didn’t have a teaching position so I went to work at… at that time it was called Hillel; it wasn’t the Portland Jewish Academy but [it was] the Jewish day school. I also started teaching music at the Foundation School at Neveh Shalom. I think I was also still teaching at Beth Israel and at the JCC. So I was doing all these music jobs. At some time or other I said to Ilene we really ought to make a recording for the kids. I guess we did It’s Time to Sing first. That recording had the songs that I had been teaching because people want to have the songs and it would be fun to have a recording of it. So we just decided to make the recording and from then it snowballed. Then we made the Hanukkah recording, Just in time for Hanukkah! and four other recordings. But the initial thing we did together was leading services at Havurah together,

Weil: Okay. The other thing we kind of skipped over, it seems to me you were involved in the cemetery, where we ended up finding the cemetery.

ROSENTHAL: It wasn’t me. It was Elden. Elden was very much involved in the cemetery. I think it was Elden’s idea initially or maybe it was Elden and David. That if we were going to be a synagogue we needed to have a cemetery. And very early on at Havurah we had some members with critical illnesses that came along. It was clear to us that if we were going to be a Jewish community it had to be supporting people in life cycle issues. And I do remember when we were looking at spaces one of the cemetery possibilities was across from Washington Square there was a cemetery spot and I remember thinking, “Hmm, being buried looking at Nordstrom’s…” [interviewer laughs] But I wasn’t involved in a big way.

Weil: Were you involved in any of the rabbi search committees?

ROSENTHAL: Yes. I believe I was involved in the search committee hiring Roy. I think I was the most involved. Yes, I guess it was [when we were] hiring Roy. I can’t remember; we had one rabbi search where we didn’t end up with anybody and we ran the congregation by ourselves for a while. And somewhere I was in one of the three and I don’t remember which one.

Weil: Okay. So Roy was with Havurah for how long?

ROSENTHAL: Five years maybe. That’s my recollection.

Weil: Okay. Somewhere in here you were president.

ROSENTHAL: I wasn’t. Elden was president twice and I helped because he was working and I wasn’t working as hard as he was. I wasn’t president until 1993. I was on steering.

Weil: Well who was the rabbi when you were president?

ROSENTHAL: Joey.

Weil: Oh, okay. During your term of office, do you recollect any big issues that the congregation was dealing with?

ROSENTHAL: The thing that I remember the most was that we were no longer able to have High Holidays at the JCC. So it was the beginning of the end of the JCC and the first thing they told us that we couldn’t have High Holidays there. I don’t remember what the fiscal year was in those days, but I remember we moved the High Holiday services to the Masonic Temple downtown. So the year that I was president was the first year that we met at the Masonic Temple. And that was a huge sort of change in who we were. Because we were identified already then as being the synagogue that met at the JCC. And all those years we didn’t charge a fee for attending those services. The JCC charged us to rent the space but it wasn’t a huge amount of money. And people made donations who came to the services; so that paid for it. But we were taking a risk because we were downtown. You couldn’t easily park and it cost more money. So that was a major shift that we had to go through and I remember that being dicey.

Weil: How successful was it?

ROSENTHAL: It was very successful. I think we had as many or more people than we had had at the JCC. Maybe there were people who didn’t want to be at the JCC and were comfortable at the Masonic Temple. I don’t know. But we were full. It was a full house and I think it was a shock certainly to me that that many people showed up. I remember kind of looking out and saying, “If you move it they will come.”

Weil: Do you have any clue of how many people were there?

ROSENTHAL: No, but it was well over 500 people. It was certainly more than double of who we were as a congregation. The other issue that I remember was raising dues amounts. We were already at the point where a large percentage were adjusting, who couldn’t afford to pay the dues. Yet we needed more money if we were going to be renting more space.

Weil: Do you remember how many families we had at that point?

ROSENTHAL: No, I don’t remember.

Weil: Okay.

ROSENTHAL: I think the other big issue was always leadership building. Who was capable of coming in and being leaders? In what areas? I think another major issue from the time we were 50 families until the present, was this discussion of whether we were going to grow or whether we were going to close the membership and leave it as it was. There was that issue, I think, during my presidency and then the other one that always raised its head was about hiring people from outside or from within. I think that again was an issue when I was president. We began the discussions about whether or not we were going to look for a building. That was contentious – it was contentious within my family because Elden didn’t think we should buy a building. He thought we should continue to rent and the building would just give us headaches. I felt strongly that we couldn’t keep relying on these various places to rent. It was clear that the JCC was beginning to say they wouldn’t even let us use the chapel. That had the sort of writing on the wall. We also looked at possibilities of buying space with a church group. We met several times with a Quaker group. Bob Liebman was my vice-president. We worked very hard on trying to meet with the members of the congregation in small groups and talk about what we each family felt about a building and that kind of thing. I remember that.

Weil: How did the congregation make the decision to get a building?

ROSENTHAL: I think that the consensus was that we wanted to have our own space. People believed that we would have enough people join because we had a building that that would be an asset as opposed to a liability.

Weil: Did many people leave when we made that decision?

ROSENTHAL: We thought people would leave. But very few people actually left. There were people that were leaving for other reasons. But I don’t think there were people that left. The group that planned the fundraising for the building did such a fabulous job of raising everyone’s consciousness about why we needed the building. Then the fundraising campaign itself was so successful. I think they said 99.5% of the people gave at some level. I think that made the difference.

Weil: You were not involved with that fundraising.

ROSENTHAL: I was not involved with the fundraising. I was on the committee looking for a building.

Weil: Do you want to tell me about that process?

ROSENTHAL: All I can say is that it was tough having been at the West Hills Unitarian Fellowship which if you were going to pick a building that would have been the perfect building for Havurah. Then looking at a variety of places, it just seemed like we’d never find the right thing. We looked. There was a church off of Hawthorne that seemed like a real possibility. We talked about sharing space with the Friends – that was on SE Stark – the Friends Fellowship. They were more dysfunctional than we were on decision making. They were wonderful people but they couldn’t seem to come to a consensus. I think those of us who were on the committee thought that that would have been the perfect thing to share a building. But that didn’t work. We looked at some other places. Then Pam Webb, a Havurah member who was an architect, showed us this horrible building on NW 18th. I can say that on the day we went to see it, it was cold and it was damp and the building was ugly. I was totally not in favor of that space. I didn’t have Pam’s amazing vision and it made no sense to me. [laughs] But I was wrong.

Weil: The affiliation issue – did that take place before or after your presidency?

ROSENTHAL: It was before my presidency.

Weil: And do you have any thoughts about it?

ROSENTHAL: I had an affinity, through camp, to the Reform Movement. But I didn’t have an affinity to the Reform Movement from the standpoint of liturgy or philosophical things. We as a community had had a pretty negative experience with their leadership – the West Coast leadership of the Reform Movement. They were not happy that we were such a participatory, non rabbi-centered group. We initially thought we would be Reform and we were for some number of years. I don’t remember how many. But the rabbi from San Francisco who came from time to time to town to try to tell us how we should run things was totally out of touch with us and with what we were doing. He couldn’t really see past the way things had always been done. So we didn’t have a good experience with him. In our first rabbi search we hired Roy. Although Roy was part of the Reform Movement, he wasn’t part of the establishment movement. And when it came to hiring Joey: Joey was a Conservative rabbi, but he heard about our congregation from a Reform rabbi that we interviewed. So I think we didn’t have a need to belong to the Reform Movement and the Reconstructionist Movement seemed like an interesting alternative. They were more in touch with the way we were leading services and leading the congregation. But I don’t think any of us, at least I didn’t feel strongly one way or the other about it. I just knew that we hadn’t had a good experience. I think that Portland at that time was still provincial enough that most of our members didn’t know what was going on around the country. I did, because Ilene and I were already doing music out in the larger Jewish communities around the country. It was clear to us that what we were doing at Havurah was on the cutting edge of what was going on not only in the Reform movement but also in the Conservative movement. So the fact that the Reform Movement in Portland and on the West Coast didn’t seem to value what we were doing made no sense to me.

Weil: So was it contentious, the affiliation question within the congregation?

ROSENTHAL: I think there were some people who were not happy with the decision. But I don’t remember it being contentious. I could be wrong. Most people had not grown up with any knowledge of what Reconstructionist Judaism was.

Weil: Okay. During this span of the life of the congregation what kinds of changes have you seen from the beginning to now?

ROSENTHAL: In the congregation itself? I think that the biggest change obviously is that those of us who have stayed involved are now the senior citizens. When Havurah started we had one or two family units that were above 45 and now those of us who stayed with it are even older than that by a long shot. So watching the families come and go, and the age differences is interesting. I’m involved now through my daughter and son-in-law. My granddaughter is part of the Shabbat school. So I see many of the wonderful things that we started are still going on. They’re different but they are still going on. I see that the congregation has many of the same problems we had even when we were 50 families. I think overall the values, the core values that we thought were important – adult ed, celebrating the holidays, the participatory nature of things, having music be a core piece of everything we do, welcoming inter-married families –those values that we started with have stayed a part of the congregation. I think we’ve changed. We’re bigger. We’re much more of an institution. We know that some of the things we did aren’t going to continue to work long term. We have this very solid but probably soon-to-be-changed image that we don’t fundraise in any big way. I think we’re realizing that we have to have a more deliberate way of raising funds that goes across the congregation and will take us into the future. But I don’t think I ever said to myself until recently, “It’s really important to me that this congregation continue.” We were doing what we were doing for ourselves at the time we were, and we weren’t really trying to build a long term institution. But I think we’re old enough now as a congregation that we have to look at that and see what it is that we’re willing to make a commitment to for the future.

Weil: What direction would you like to see the synagogue go?

ROSENTHAL: I think that we are different than the rest of the synagogues in town in that we are growing faster. [That] is what I’ve been told. And part of the reason we’re growing is the religious school. People seem to be – young families seem to still be drawn to the way we do the religious school and the active involvement of the parents. But I think that if we’re going to keep our participatory nature intact we have to make it clear on the front end that you don’t join just to be in the religious school. And I think that message has probably been lost the last few years.

So I’d be happier with 300 very involved families than 400 families where 100 of the people are only involved in the religious school. I think that’s a key. I think that if we are going to hang on to that participatory piece we have to figure out how to make people understand when they join that part of their responsibility and part of the joy of belonging to Havurah is that participation thing. The reason I say “joy” is that as frustrating and time-consuming and hard as it can be to participate in either leading the services or leading High Holidays or leading things for the school or whatever, or fundraisers or whatever, I think that we all gained amazing strengths from that experience. I wouldn’t have done the music that I did if I hadn’t had this opportunity. If I had stayed a member of Beth Israel or had joined Neveh Shalom I probably would have done some music but I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to grow in the area of Jewish music. I think it’s the same with leadership skills. We all were required to take leadership roles. And our kids were asked to be in leadership roles from a very early age: to lead services; to get up in front of people and talk; and to study. Those kinds of things we did in a way that I’m not sure we would have done if we belonged to a synagogue that had a huge staff where everything was done for you. So I think we have to figure a way to continue to give people that opportunity and then nurture that ability. And I don’t know exactly how to do it but I think that is the key.

Weil: Do you want to talk about your involvement in either the Jewish community or the broader community?

ROSENTHAL: Well I’ve always been involved in the Jewish community, not just Havurah. I was involved at the JCC. I helped with the resettlement of Russian Jews. And I was part of the network of Jewish musicians in town. I was involved through Havurah in the neighborhood association in NE Portland. And through that I got involved in tutoring kids with reading problems. That’s how I got involved in starting the non-profit that I helped found.

Weil: The name is?

ROSENTHAL: The name is Reading Results. It started by actually doing tutoring in conjunction with…. What was it called? Do you remember?

Weil Was it SMART?

ROSENTHAL: No, no. Havurah had agreed to work with the neighborhood association in inner NE and North Portland. And I can’t remember what that alliance was called. But as part of that I started with kids who had reading problems. That snowballed from there. I think volunteerism is hard for working families where both people are working. But even when I was working full time, I always made time for the volunteer parts of things either in the greater community or in the Jewish community. I kind of wish families could make more of a commitment to that now because I think it enriches our lives.

Weil: Okay. Is there anything else that you want to add? That you can think of that I skipped?

ROSENTHAL: I think that in the beginning, part of us wanting to join as families who had kids the same age was that it was that it was difficult to be Jewish in Portland. My kids went to an elementary school where there were maybe two other Jewish kids. We felt strongly that if we were going to try to bring them up Jewish, they needed a community to be connected. The people that we met through Havurah were more like us and shared more of the values than the people we had met at the larger synagogues. I think that tie followed us through the entire experience of our kids being in Havurah. They both have a strong Jewish identity and feel that Havurah was a good experience for them as kids.

Weil: Well it’s wonderful to see the next generation at Havurah, which your daughter is, and your granddaughter. That’s very nice. All right, anything else?

ROSENTHAL: No, I think that’s it.

Weil: Okay, thank you very much, Margie.

ADDENDUM:

Weil: This is Joan Weil August 20, 2015. This is an addendum to the interview I did with Margie Rosenthal in May of this year. There were a few things that we skipped over having to do with music at Havurah during her whole time as a member. Let’s start there.

ROSENTHAL: I wanted to give some context. I think I mentioned in the earlier interview that I had gone to Camp Saratoga, which is now Camp Swig, where I got inspired about music. I learned to play the guitar. In the mid-‘60s, when I was in my later teens, I did music at religious schools and in nursing homes in the town where I grew up. When I was in college I continued to do that. I think a big thing that got me interested in Jewish music more than just the silly songs we did at religious school was that in 1968 I went to Europe with my roommates for a trip. When we were in Amsterdam there was a coffeehouse called Jerusalem of Gold that was very near our hostel where we were staying. I ended going every night after my roommates would go to bed or maybe they were off partying somewhere I would go to Jerusalem of Gold and learn and listen to the music. I learned a lot of Israeli songs and got the names of Israeli artists and that kind of thing so I was able to learn the music.

In 1972 we moved to Portland from California. I went to work at Beth Israel teaching music for the religious school. I had a regular job; I was doing regular teaching. But I was also doing religious school. I worked with Rabbi Rose and Rabbi Kane at Beth Israel. But I was not at that time participating in the service itself. I was just doing music for the religious school.

In 1973 or ’74 Alan Berg became the assistant rabbi at Beth Israel. Alan had a real creative streak and was very interested in the combining of secular and liturgical music to make the service more interesting and more participatory. Alan and I started something called the Miller Room Service. They had done it a little bit before, but I think it was fairly new at that time. The service was a regular Friday night Reformed service but Alan would interject interesting readings. Usually they were topical, not necessarily related to the Torah portion but topical on some social issue or some world problem that was going on. I would try to find some music that went with that.

We did that for a number of years. Beth Israel sent me to California to work with Cantor William Sharlin of Leo Baeck Temple in West LA, who was a major music person in the Reform Movement. Cantor Sharlin taught me several melodies for traditional prayers like the Barchu and there was a different MiChamoha and that kind of thing. I began to incorporate those melodies into the melodies for the Friday night for the Miller Room. Neveh Shalom had a wonderful library of music I would go there and get music.

So a little at a time I acquired music to enhance a service. Probably about 1976 or 1977 Rabbi Berg and I also did Yom Kippur afternoon services at Beth Israel in the sanctuary. That was sort of a renegade thing to do because they hadn’t had the guitar as part of the service. Their afternoon service was a smaller, more intimate service and the cantor didn’t traditionally…. At that time they had a hired cantor who was not Jewish. His name was Bill. I can’t remember his last name. He was a lovely man and he had a beautiful voice but he wasn’t Jewish. He was just hired to do the High Holidays. For the most part he didn’t do Friday nights. He might have done bar mitzvahs.

Weil: Who were the people who came to that afternoon service?

ROSENTHAL: The afternoon service was a real mix of the people. [It was] in the Miller Room. I met people like the Rackners, Alvin and Shirley. I met Natalie and Merritt Linn. I think I met the Chestlers. I might have met you guys. There were young people my age in their 30s but there were also older people who were enjoying the different kind of thing. But within the Beth Israel community there were people who were very unhappy with the idea of guitar in the service because that was new to them. We did the history on Havurah and how Havurah got started. I think what was important to the early Havurah services and celebrations was we made a commitment that we would have music infused in everything we did. I continued to try to find the right kind of music. I used Rabbi Berg as a resource. At that time Mark Dinkin was at Neveh Shalom. He didn’t really know a lot of folksy music but he helped when he could. I got recordings of things. All of our holiday celebrations, our Friday night services, everything had music as part of it. Then we had the good fortune that Alan Berg connected with Aryeh Hirschfield who at that time was not a rabbi but who had trained and learned music with Zalman Schachter and a couple of other people on the east coast. Aryeh was aware of this sort of wave of new age Judaism I’m going to call it. It was what we were doing in Havurah. We came to it on our own. We didn’t come to it because somebody was on the east coast and saw something happening. We organically developed it at the same time it was organically happening in other communities. Aryeh not only had new resources to bring us but he also wrote his own music. We incorporated that into our services. Aryeh came from time to time and led music and taught Ilene and myself the music.

Weil: Did Debbie Friedman come in here at any point along that time?

ROSENTHAL: Debbie’s music, her early music in those days was more the camp music. But by the mid ‘80s there was Debbie Friedman music available on recordings and that kind of thing. Emily Gottfried who was a member of Beth Israel and who was quite a bit younger than me, when I met her she was in college still. She had been at Camp Swig with Debbie Friedman. So she came back with other music. She wasn’t working as a cantor then but we shared music. Whenever there was an opportunity to share music anywhere we were there. Either I was there or Ilene was there or somebody was there with a tape recorder and trying to glean as much music as we could.

As I said before in the earlier interview, we met because of a mutual friend – our mutual Havurahnik. After they joined we began to collaborate on leading Friday nights. We collaborated on leading the high holidays. As I said before, Ilene had a strong Judaic background and read Hebrew and knew much of the traditional music. We were able to create services that were of the traditional and the not-so-traditional music. We tried to have our services [include] songs and melodies that were easy to learn, that people could clap along to. That didn’t have too much Hebrew. We usually provided some kind of transliteration so people could join in. And a little at a time everybody learned all the melodies. Our services were always joyous and fun. I think that the beauty of Havurah that has still stayed is that amazing participatory nature. It’s really evident on High Holidays. It’s really evident at Kabbalat Shabbat, It’s evident at b’nai mitzvot that this community doesn’t just sit with the books but we join with each other in singing. I think that has been some of the glue that has held the group together. When you ask people what’s one of the most important things about Havurah they always say the music. We have a lot of people to thank for that. I feel lucky to have been part of the catalyst for making that happen. A life-cycle event or a service with somebody up on the bima or in the front of the room singing and nobody engaging is foreign to me now; I just can’t imagine it anymore.

Weil: A lot of people joined Havurah playing music and to take part in the singing, leading the singing. There were a lot of people that came. I’m thinking of Barbara Slader. There’s a whole group of people who came on and wanted to take part in that.

ROSENTHAL: Right. I think that it was infectious in a way. People who had musical ability were drawn to Havurah because there was this sense that if you could contribute, you were welcome. Barbara Reynolds (her name was Barbara Reynolds at that time) was not even Jewish. But she was a friend of Ilene’s. She had met Ilene at work and she was so taken by the services and the spiritual nature of things that she began to study. We would give her recordings. She would go home and learn and pretty soon she was part of the service. When Emily Gottfried moved back to Portland from Albuquerque or wherever they were, because she was so musical she decided that even though she grew up at Beth Israel that she wanted to be part of the music of Havurah. So she became part of it. There’ve been lots and lots of people who have done that, some of them have really strong talent in leading music. Some of them just play instruments. We try as best we can to get those people to participate whenever possible.

As I think I said in the earlier interview, Ilene Safyan and I became very good friends and really enjoyed doing music together, both Hebrew music from the service and Israeli music and secular music too. In the mid’80s I had stopped teaching. I had been teaching at Beth Israel’s pre-school, at Neveh Shalom, at the PJA’s pre-school or their whole school. For the Parks and Recreation Department I was doing Jewish music. And then I knew I was going to be gone; we were taking a sabbatical in 1990. I asked Ilene, who had quit her job, if she would be willing to take over the music jobs. She did take over some of them; I don’t remember whether all. Then I gave her all the music I was doing with the little kids. She had some of her own from her background.

Somewhere in the late ‘80s we decided that we should take these songs, mainly Jewish songs, and make a recording. We made our first recording called, It’s Time to Sing. It was just done really cheaply. I think we were doing it as a fundraiser for the JCC pre-school. Somebody donated a recording studio. We went in and in a couple of hours we recorded a bunch of songs. We had some kids on the recording also. In those days it was cassettes. On one side was all Hebrew music and on the other side was secular fun kind of songs. That was really popular. We didn’t print up fancy labels or anything. We just kind of typed little cards to go on them, whatever, but they started selling. Then we went on to do three more albums, Just in Time for Chanukah, which won a Parent’s Choice magazine award and was picked up by the libraries around the country. We began to sell them all over the United States. Then we did a lullaby CD and a CD called, Shabbat Songs for Families. We also toured a little bit doing music in other communities and teaching workshops on how to infuse music into curriculum.

All of this came from our opportunity to participate in Havurah. That would not have been something that I would have naturally done or had an opportunity to do without Havurah giving us a platform to explore our creativity. I think Havurah has done that over and over again. There are people who have written amazing poems and pieces that we have incorporated into our services. We have a really unusual Al Chet that we do on Yom Kippur that was written by Stew Albert and his wife Judy that is as good as anything that you’d read published by some organized Jewish publication. That’s happened over and over again where people have been asked to lead a service. They get inspired to either do some music or do a sermon or create their own reading. Suddenly they have created something beautiful. I think Havurah gives that opportunity in a way that no other institution in Portland does. I think that’s one of the key exciting things about the congregation.

Weil: Okay. Is there anything else that you wanted to talk about?

ROSENTHAL: When Rabbi Joey Wolf joined us as our rabbi he came from a Conservative background. I think it was probably a little odd for him in the beginning to come and join this unusual group, where we were not rabbi-centered, where the rabbi had to kind of push his way through to get time on the bima. Not only did we learn from Joey but Joey learned from us: different ways to lead a service, different ways to make people feel wanted and comfortable in being part of the service with him. Now he nurtures everybody to do that. He reaches out to different people every year, both the Friday nights and Saturday mornings. If you go to even Wednesday minyan he’s got different people leading all the time. He became comfortable with not being the center of attention. He’s made other people be comfortable as leaders. I think that’s a real strength of his.

Weil: Okay. Thank you very much. I appreciate your calling to my attention that there were other things we needed to include in this interview.