Leland Lowenson

1902-2001

Leland Lowenson was born in 1902, in Portland, Oregon to George and Daisy (Dorothea Hermann) Lowenson. The family had been in Portland since 1883, and in San Francisco before that. They lived in Northwest Portland and Leland attended Couch and Ainsworth Grammar Schools, Lincoln High School, and Stanford University. His family was involved with Congregation Beth Israel, where Leland was its first bar mitzvah. He married his wife, Celene, in 1933 at the height of the Depression, and they had two children, Lynn and Lee.

Interview(S):

Leland Lowenson - 1978

Interviewer: Ruth Semler

Date: May 17, 1978

Transcribed By: Anne LeVant Prahl

Semler: Leland, I would like your earliest memories. What do you remember about your grandparents, including their names?

LOWENSON: Well, my grandmother on my father’s side was named Ida Davidsohn. She came from Dansig, Germany. In East Prussia. My grandfather on my father’s side’s name was Leopold Lowenson, and he came from Tilsek, which was also in East Prussia, or Bohemia, I guess it was. It has disappeared from the face of the earth because it was one of the cities that was bombed out of existence during World War Two. It was completely destroyed. My grandmother on my mother’s side was an Adam. I just got a letter a few minutes ago from one of the Adams who lives in New Zealand. We just visited with them, and he will be here in about ten days to visit with us. My grandfather on my mother’s side’s name was Hermann. Benjamin Hermann. He came from somewhere near Cologne. [Benjamin Hermann’s obituary (1911) confirms that he was born in Cologne]. The Hermanns were married in Europe and moved to St. Louis; their first child was born in St. Louis. [Son Lee Lowenson believes that Minnie was born in Germany in 1868. There is some question about whether the family ever lived in St. Louis- see accession file for notes]. That was Minnie Lowenson, [Minnie Hermann and Dorothy Hermann married brothers George and Max Lowenson], Silv and Dorothy’s mother. Then the family went back to Germany. They expected to stay there, but they didn’t like it. They came back to the States and moved to San Francisco. The rest of the children were born in San Francisco, including my mother. On my father’s side they had a similar story. They were married in Europe, and my uncle was born in Europe. They had been in San Francisco but decided that they didn’t like it and went back. They came back to San Francisco, and that is where my father was born. Both sides of the family are three generations of native San Franciscans.

My father came to Portland at a very early age. I think he was five years old, the 4th of July, 1883. I have it written down here. They had been in business in San Francisco, and they lived on Matoma Street. It was only two blocks long. One block was destroyed when they built the Bay Bridge. The other block is still there; I have seen that. The house is gone. The business that my grandfather founded on Bush and Franklin Street was in the family until about ten years ago. They owned that store for ninety years; that was a market. My grandfather was a butcher in Europe, and he was a butcher here. When he came to San Francisco and started the butcher shop, they didn’t buy from slaughter houses and things; they would go buy directly from the rancher. There were lots of Italians there. He usually went across the bay, sometimes as far as San Jose, sometimes into Sonoma County to buy cattle. He used to buy the cattle, and they would sometimes slaughter it and send it to him in San Francisco. But if he was short of meat, he would tie a couple of cows to the back of a buckboard wagon and bring them back across the bay to his market in San Francisco. The market was much more primitive. At the same time, most of those Italians raised wine grapes and pressed their own wine. He usually brought back a half-barrel or two (a full barrel is 60 gallons, so these were 30) in the back of the wagon. Later, when my father got married and moved to Portland, my uncle and grandfather used to ship the wine up, a barrel of white and a barrel of red, every fall to Portland, and he would pay for the transportation of it. My father told me that he paid 15 cents a gallon to the growers, which included the barrel, so you can see they didn’t pay much for the wine. When he shipped it to Portland, my father being in the business, they had lots of hauling. The transportation company (owned by the Hermans of Portland – no relation to us) would haul the wine up to the house for nothing (because they got the business of the store) and let it settle. I can remember from the time I was six years old, my father and my uncle worked six and a half days a week and into the evenings. Sunday by noontime there was nothing doing, and they would come home and start the bottle of wine. They would take a siphon and suck on it to start it and fill each bottle. My job was to clean the bottles from the previous year. They gave me a lot of shot. I put the shot in the bottle and shook the bottle to get the sediment out of it and cleaned the bottle good. Then I put them in a big wash tub in the basement to wash. Then we bottled the wine. They would divide the two barrels between them and then sell the barrels to [can’t hear] here in Portland, and they made enough money selling the barrel to pay the expenses that they had, so actually, we had wine for nothing. I never drank milk. I still don’t. I always drank wine. They didn’t give it to me straight; when I was a little guy they cut mine in half with water. We had wine for lunch and dinner. I was raised on wine.

Then, when we would have dinner on Sunday; it was quite an affair. My uncle and my father had been siphoning wine all day. They had swallowed a little wine [laughs] accidentally. So it was quite a festive dinner. My grandfather in San Francisco had a little market, a little store or something. And they heard that there was going to be the Vollard Boom here in Portland. Vollard was the fellow that built the Northern Set Railroad. There was a race on between the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific to see who would get it here first, and there was quite a boom. Everybody thought that with two railroads and only one coming into San Francisco, that it would be a big thing. So they came up here from San Francisco. The only communication was by water. They came on a ship. I think it was the Columbia, and it sank the next trip or two trips later. But this time it came up. And when my grandfather came up (this was my grandfather Lowenson), he came up the Columbia, and there were all forests on both sides. He said, “In 50 years, these trees will all be gone and it will all be vineyards.” Well, he was half right. The trees are gone, but there are practically no vineyards. But they are now starting a vineyard culture industry here in Oregon. There are 27 wineries here now, or something like that.

So they came to Portland. They had already had a store planned. The Mishes, that were related to the Gevurtzes (several of the Mish girls married Gevurtz boys, I think) were already here. They were building a two-story building on First and Hall on the Southwest corner; this was in 1884. On July 4th, 1884, the Lowensons got out at the foot of Ankeny Street. They were looking for a good place to stay because it was pretty wild on July 4th weekend. There were lumber camps. The only time they shut down the whole year was 4th of July. So they sat up with their two small children (my dad was five years old, my uncle was two years old). They sat out in a hotel lobby all night; there was no other way to be off the street. I don’t know where they stayed the next couple of days but eventually they moved up to the corner of First and Hall. They might have lived upstairs over this building because they rented one of the two stores from the Mishes downstairs, and it had two apartments upstairs. They occupied that building for quite a while. That building was still there until Urban Renewal, when it was taken down. I have a picture of it because when they did the Urban Renewal, they took pictures of every building before they tore it down. It is where Jade West is today. The corner isn’t there anymore because it has all been reconstructed, but that is where it was.

Because of the Vollard Boom and the excitement of the time, they named the first store the Northern Pacific Bazaar after the Northern Pacific Railroad. In San Francisco it had been called Leopold Lowenson’s. Then there was the plan of calling it the IXL or the Emporium, or putting on a name that sounded much more metropolitan, and then they called it the Northern Pacific Bazaar.

Semler: What did they sell at the Bazaar?

LOWENSON: They sold everything. It was a general store. Of course, clothing was practically all hand-made and so were shoes. They sold thread, needles, suspenders, shirts and underwear for men and women. They had all kinds of piece goods, blankets. My grandmother was really the merchant. My grandfather Lowenson was more of a student. She was the one that would make a trip to San Francisco twice a year to buy the merchandise for the store. They had accounts in those days. She didn’t keep them, but she would tell my father and my uncle, “Put it in the book.” Or she would say, “Who was that lady that just came in?” And they would say, “I don’t know.” And then she’d say, “What did you give her?” “I gave her some ribbon.” “How much did she give you for it?” “She didn’t pay for it.” “Is she going to pay you for it?” “Yes, she is going to pay.” “So put it in the book!” So they would put into the book: “The lady with the red hair took two yards of ribbon.” And 30 cents or 15 cents or whatever it was. That is the way they kept their books. There were government requirements for a limited [??]. If they had enough money left over at the end of the day, they paid the cash out, and if they didn’t, they paid it a little later, I suppose. There was a lot of credit given in a small way. No one ever researched credit; it was just on their face.

The business went fairly good. They made a living. The Vollard Boom petered out eventually, but they got along. The store was moved several times. First it was moved north because the whole town went north. Originally, they thought it was going to move south, but it didn’t. One reason why they moved to the place on First and Hall was that it was, not the end of the horse line but the horse car ran up First Street, and there was little hill there, about four blocks long, which has disappeared now that it was graded. They put a hill horse on there. They had one horse most of the time, but at the bottom of the hill, to get the horse car up the hill, they put on another horse. Then, at the top of the hill, when it leveled out again and went further into South Portland, they took the hill horse off. Well the car had to stop there, so that is why that was a very fine location. The car stopped right in front of their store. They couldn’t miss. The hill horse was put on the back of the next car as it rode down the hill. Then you rode down for nothing on the back platform, down till the next car came and they pulled it back up again. A little while after that they put in cable cars, but at the time that they started this store, that is the way they handled it.

Semler: Now this store didn’t sell any food?

LOWENSON: No, it was just a bazaar, a general store.

Semler: Would you also tell me the names of your grandparents?

LOWENSON: My grandfather’s name was Leopold Lowenson. My grandmother’s name was originally Ida Davidsohn.

Semler: And what was your father’s name?

LOWENSON: My father’s name was George Lowenson. He didn’t have a middle initial, but when my mother married him she said that everybody with any dignity or importance has to have a middle initial and she gave him the middle initial “J.” I don’t think he ever used it, but it was on their calling cards in those days. He never had a name to go with it.

Semler: And what was your uncle’s name?

LOWENSON: My uncle’s name was Max. And my mother’s Christian name was Dorothea, but many people called her Dorothy. Many people that knew her as a girl in San Francisco, because she lived there until she got married, called her Daisy. I think you will see her name as Daisy as much as you would see Dorothy.

Semler: So your grandmother and your grandfather and your uncle started this bazaar?

LOWENSON: Yes, my grandparents and my uncle. That’s all the Lowenson family was. There almost was nobody else ever in the United States by that name. There were some Davidsohns that came over here. But the Hermann family, except for my mother and my aunt Minnie, all stayed in San Francisco where they still are. They were all really pioneers down there.

Semler: After you moved from First and Hall, where did the store go to?

LOWENSON: Well, it went to … just a minute. I think I have it on a picture downstairs.

After First and Hall it moved to First and Taylor, and there it was called L. Lowenson Dry Goods. They decided to put their name back on it because the Vollard Boom had pooped out anyhow. It said, “L. Lowenson’s Foreign and Domestic Dry Goods.” I have a photograph of that with the prices in the window and so on. Then it was (the Lowensons didn’t get into any trouble that I know of, but) they got to have a very large store on Third and Oak. They went back to Chicago Clothing Company. Chicago was the big market for men’s clothing, so that sounded very impressive. It was just a question of names and the fashion of the times. In 1922, after the death of my uncle Max, we moved it to West Park (which is now called Ninth) and Washington. It was called Hart, Schaffner and Marx Clothing Company. My dad was partner with the Rosenblatts there and in two stores. The other store was called Rosenblatts. My dad was a managing partner in that. That didn’t work out too well, so they bought Rosenblatts out of that store, and they bought us out of the other store. We continued the business with the name Lowenson on it again. It remained Lowensons until we finally closed the business in 1975 because my son Lee didn’t like the clothing business. So after 93 years, the Lowensons are out of the clothing business. He’s moved to Hawaii. He was the fourth generation in the store, and he did a very good job with it. He just didn’t like that kind of work. The sign that we originally had in the store, “L. Lowenson Foreign and Domestic Dry Goods,” we continued with and right up to the end of the store. Except during the war when we couldn’t obtain them, foreign goods were an important part of our stock. We continually upgraded the store, and of course, in the early days there wasn’t very much deluxe merchandise anyhow. People were just trying to eat and live. As things developed, finally, by the time the store was closed, we had the finest store in Portland and probably equal to anything on the West Coast. Lee went to Europe and continued that buying tradition very successfully, but that was the end of it.

Semler: It is sad to see something that has been a part of your life forever end.

LOWENSON: Yes it was, but a business is just a business. Oh here is some of the … see the original building was built by the Mish family that occupied the second floor in the first location. Oh, the first place it moved was to Jefferson and Columbia. Then it moved to First and Taylor and then to Third and Oak. Incidentally, it is not part of our family, but the family jingle, the Mish family. Have you interviewed Sylvia Holzman or anyone?

Semler: No, is she part of the Mish family?

LOWENSON: Yes, her mother was a Mish. Anyhow, it was a very large family, and it had a jingle. It started out: “Becky, Mary, Simon and Joe, Julie the baby and Manny and Moe.” That was the whole family. She remembers the rest of that. You will have to ask her about that.

Semler: I surely will. I wasn’t aware of the Mish family before this.

LOWENSON: Mrs. Holzman was a Mish.

Semler: Were there no sons in the family and the name died out?

LOWENSON: There were Becky, Mary, Simon must have been a Mish, and Manny and Moe. It was a pretty good sized family.

Semler: I’ll have to ask what happened to them. Tell me, what do you remember about your father and your mother and about what they said about Portland in the 1900s?

LOWENSON: They were always very enthusiastic about Portland. They always liked to travel. When they were first married they lived for a year at the Hobart-Curtiss, which was just torn down this year. It was a very fashionable residence hotel. It was right next to where Lincoln High School is now. You know, that seven story building that was just torn down on 14th at the end of Salmon Street.

Semler: Was that the one that was finally the Martha Washington and the Joan of Arc?

LOWENSON: Yes, that’s the one. It was a dormitory recently. I can remember Mr. and Mrs. Charles F. Berg when they were first married lived there. Anyway, when I was expected, they rented a house at 566 Hoyt Street, which was on Hoyt Street between what is now Seventeenth and Eighteenth Street. The street wasn’t paved yet. I can remember it when it had wooden sidewalks. I walked along sticking an umbrella in the cracks and bending the umbrella, and then I’d end up with an umbrella bent over my back like that. But I did it repeatedly. And there was a Chinese laundry in the basement of the house in the next block. My aunt lived on the next block. There were a number of fine Jewish families that lived up there. In fact, the house that I lived in was recently designated an historical monument. A landmark. It has been published in the paper. The whole block has been restored. [shuffles papers]. It was this house right here. I was born upstairs in that house. The Markewitzes lived on the far corner up here, and the Harris family (who were mostly school teachers) lived here, with two boys and five girls. And some people by the name of Solomon lived in between. I can remember all of those people.

Semler: Tell me. Your father was in Portland and your mother in San Francisco. Did he return to San Francisco regularly so that he met her there?

LOWENSON: No he didn’t. My mother came up here to visit my aunt (Minnie Lowenson, Max’s wife) as a young girl, an eligible girl. And she was introduced to my father. She was a very beautiful woman. She was always the “belle of the ball” in San Francisco. They used to actually designate someone the “belle of the ball.” It was a title, and after the ball was over, it was written up in the papers. She was a very beautiful girl, and it wasn’t hard to get my father to fall in love with her. So that seemed like a good marriage, so I guess it was. Then, when I was going to come along, my mother’s friends were all in San Francisco (not all, but most of her girlhood friends were there because that is where she was brought up). I have all that kind of material here. And she wrote to an old friend of hers who was in Europe studying to be a doctor, and said that she was expecting a baby, and in the course of the correspondence the friend asked, “What are you going to call it?” My mother said, “If it’s a boy we are going to call him Leopold after his grandfather.” The friend said, “You can’t do that to a boy. That is an old-fashioned, archaic name. It is a terrible name in the United States.” She had gone to Stanford University, and at that time, it was called Leland Stanford Jr. University. So my mother acquiesced, and that was why I was called Leland. Incidentally, I went to Stanford, and my daughter also went to Stanford. So we had a close connection there.

My aunt’s house, which was on Seventeenth and Irving, was also designated a historical monument. It is a queer thing that in the same family this would happen. It is still there. Those houses have been preserved. They were really fine houses; I can see why they would be preserved. The one that we lived in and the whole block was owned by a man by the name of Henry Trakeman.[??] I can remember Mr. Trakeman used to come around on the first of the month at dinnertime. He used to collect the rent. As I remember, the rent was $25 a month. That is one of my earliest memories. It was more than my father could afford; it was probably a fourth of what he was making, maybe more. But for his bride, you know, he felt that they had to have it. They lived there until I was five years old; then they built the house on Main Street.

Semler: Where was that?

LOWENSON: On Main between Vista and St. Claire. St. Helen’s Hall was across the street. I went to St. Helen’s Hall kindergarten before I started school. Incidentally, the King’s Addition there, those two blocks on Main Street, they are now attempting to make those two blocks an historic landmark. I don’t know how far they will go. For one family to be involved in so many historical landmarks when we are not really so historical a family is kind of surprising. We had nothing to do with it, but anyhow.

I have been down to that house. It has been renovated, and it is a lot better than it ever was when we lived in it. I have a picture taken in the front parlor. If you notice the wrought iron fixture that we have on our front door here in this house; that was in the front parlor. It had been a wedding present for my mother. It came from Spain, I think, and it had an oil lamp in it. Of course, when we lived there, we had gaslights. We burned wood. Everybody did. Slab wood was out in front of everybody’s house, cordwood. Actually, we did the same thing when we first moved up to Main Street. The automatic telephone had just been invented. So we went with the Home Telephone Company (which went out of business because they couldn’t compete with powers that be). When we moved up Main Street, I was only six years old, but about three or four years later, Hughes Electric Ranges were invented and we put [??].

Semler: Tell me why were you so anxious have an electric range.

LOWENSON: Well I was always interested. I wanted to be an engineer. In fact, I took engineering at Stanford. When we built the house on Main Street, electricity was still not too viable. All of our fixtures were combination electric and gas. But by this time, electricity was dependable. Like everybody else, we started with the Northwest Electric Company. But they didn’t have enough power for the electric range, so when we switched to the electric range, we had to go with Portland General Electric. We’ve had electric stoves ever since. As everyone knows they’ve had some really outstanding developments. I was also interested in electric trains; I had an electric train when I was a little boy. I liked everything that had to do with engineering. I liked to do my own repairing and wiring.

Semler: That is a real bonus today.

LOWENSON: Yes, it sure is. I don’t think I could afford to live here if it weren’t for that. Our taxes have gone up almost 500 per cent in 24 years.

Semler: I know that is terrible.

LOWENSON: It’s the same all over. The general inflation is the characteristic. My dad was in the real estate business for a while. I think he made more money out of real estate than he ever did out of the clothing business. But not by keeping it – by buying and selling it. He didn’t operate it, except for one piece of property. He and my uncle had an architect whose name was Amos Schacht. Not Jewish, but he was a German. There was a very close feeling here between most of the Germans and Jews. The Jews that came to Portland originally, before 1900, were mostly German Jews. They were closely affiliated with the German population; there wasn’t really very much differentiation. They started the Turnverein and Turner Hall. Of course, later on when the political differences appeared, they didn’t get along all that well. But all these people that I can remember so well as best friends. There were equal numbers of them. They would play cards together and met together. There was a German daily paper here; they all took the same paper.

Semler: So there was a lot of social mixing between the Germans and the Jews?

LOWENSON: Oh yes, they were all Germans. They were not Jews, they were not Catholics, they were Germans. They spoke a common language and had all come here to do their different things. Mr. Schwindt was a cobbler; he wasn’t Jewish. And Mr. Bodifer was in the electrical business, I think. Mr. Allard was in the hardware business. [names a few more that I can’t hear].

Semler: When did that kind of socializing end?

LOWENSON: It ended when the First World War came along. All of the sudden nobody wanted to be identified as a German anyhow. The Germans were even sensitive about it.

Semler: It didn’t end because of antisemitism. It ended because of the war.

LOWENSON: Well, that was the beginning of the end, but the final blow, of course, was antisemitism. But originally there wasn’t any antisemitism. I never heard my grandparents on either side say that they came to the United States because of antisemitism. The reason they came was the reason that most people came, and that was compulsory military service. That is what compelled them, and the opportunities of the gold rush, free land. Those things attracted people to the United States. If they were a butcher, they could continue to be a butcher, or if they wanted to be a merchant they could do what ever they felt capable of doing and could do the financing for. It didn’t take very much financing in those days; it wasn’t hard to get. Everything was gold.

Semler: Leland, do you have brothers and sisters?

LOWENSON: I never had brothers or sisters. I had a sister that was stillborn. In those days they didn’t have medical knowledge, and there was no reason why she should have been stillborn. There was nothing wrong with the child, but she was strangled by the umbilical cord. It used to be that if they would twist in the process of birth (which was fairly common then), they didn’t know how to save them. Today that doesn’t mean anything; you don’t even hear of it. It was fairly common in those days. That was the only relative I ever had.

Semler: And your uncle Max and aunt Minnie?

LOWENSON: They had three daughters. One died at Stanford University during the flu epidemic of 1918. Loads of people had the flu down there, but she was the only one that died at Stanford. The other two, one is Mrs. Lawrence Selling and the other is Mrs. Sylvan Durkheimer.

Semler: Oh, so those are your first cousins?

LOWENSON: So that cut our family very short because two brothers had married two sisters. And there were no boys on that side and no girls on our side.

Semler: Oh, I didn’t realize that your mother and your aunt Minnie were sister-in-laws.

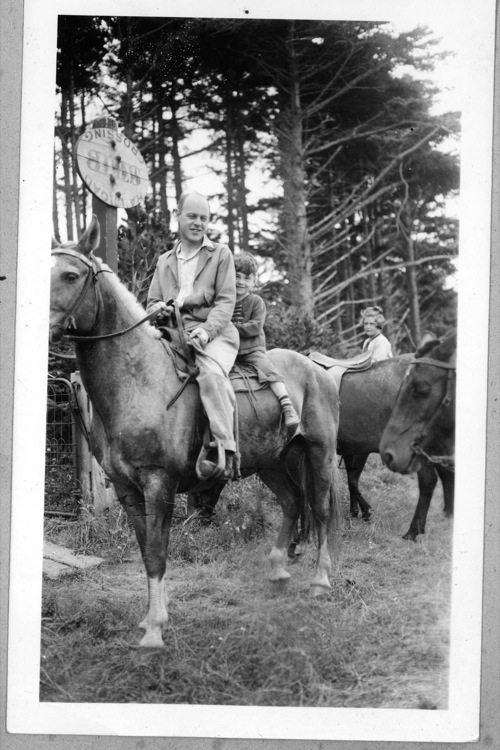

LOWENSON: That’s right. That is how they happened to come to Portland. I think you have some pictures up there, which I can show you later, of my mother’s first visits to Portland.

Semler: Your father was in business all of those years; your mother must have been very active in the community.

LOWENSON: My mother was very active in the community. Her favorite thing was the Neighborhood House. She taught cooking there. Then she also was on the original censorship board. They used to have a local chapter of the National Board of Censorship for movies, when movies first started. I can remember when I was a little guy, she used to take me to the previews. Every movie was viewed and had to be “passed” on before it could be shown in the theater. So I was a great moviegoer.

Semler: How old were you then?

LOWENSON: Oh, different ages, from seven or eight up to ten or eleven, I suppose, maybe later than that. She stayed on the Board of Censorship almost as long as they had it. But I didn’t go; I had other interests. I am pretty sure that you have this picture up at the archives. That is my mother. She was also instrumental in organizing the sisterhood at Beth Israel.

Semler: Was she a president of the Sisterhood there?

LOWENSON: She was secretary and treasurer. But I don’t remember her being president.

Semler: But she was active in the community in one way or another.

LOWENSON: That’s right. I have a citation she got during the war in the Red Cross. She was something or another. My dad never liked public activities; he supported them. I have one of the old ledgers here. Remember I told you how loosely they kept books? But they did put everything down in the book. And in the daily ledger there you will see that there is hardly a day that went by but that somebody didn’t come in and ask for charity. And they always gave them something. It ran from 25 cents to a dollar. It might have been higher than that. But a “dollar a day was the white man’s pay.” They used to say in those days. Because Chinese worked for less than a dollar a day. So if they gave them a dollar that wasn’t too bad; that would pay for labor. And these appeals were every day. You’ll see days when five or six people came in. Nobody got very much, but they all got. There wasn’t any Community Chest. We didn’t have welfare agencies or these other things. My grandmother was active in the Temple. I wouldn’t say she was terribly religious, but they were also members of Ahavai Shalom. And my grandmother sewed for the society that made the burial shrouds. I know she used to call it the “Abra kadabra” [laughs – she meant the Chevra Kadisha]. She always attended a Jewish funeral, whether she knew the people or not. She had a great penchant for small charities of all kinds. I don’t think she ever turned anybody down; if she had ten cents in her pocket, he would give it to anyone who asked.

Semler: Were most of the people coming in asking for charity Jewish people?

LOWENSON: Oh no, anybody came. There weren’t too many Jews coming in, because there weren’t too many Jews. But if some of these fellows with the long beards and the black hats (they were itinerants, they didn’t live here) would come by, they never got turned down. Neither did anybody. There were all kinds of charities. Some were church charities.

Semler: So you were recognized as people who were charitable.

LOWENSON: The merchants always were; all of the merchants were. I don’t think you could stay in business if you weren’t charitable. It was only later when they began to get more organized in charities. Then they came in and wanted substantial amounts, and you couldn’t give to everybody on that kind of a scale. It developed into something like everything else we do in a bureaucratic society. I guess that is part of the development of the country.

We always kept in touch with our family, like I mentioned. And when we were in Czechoslovakia (twice we were there in recent times), I looked in the Jewish center there to check on the name Lowenson, which is not a terribly common name. In the Tielsen [?] area, there were some in Dansig, in Tielsig [?] and in Prague. There were different families, but I am sure it was all the same family. The only ones I could identify were ones I had heard mentioned, all the ones that stayed there…

The only ones that got out that I ever knew of was a Dr. Martin Lowenson. He was a dentist, and we brought him to the United States, if you can say that. All we did was help him to get here; he died in San Francisco. He was practicing dentistry, but not as a dentist. I think he was a dental technician or something.

Semler: But the rest of your family was lost in the Holocaust?

LOWENSON: All of us, yes. There are some other Lowensons; there is one in Milwaukee, Wisconsin that we know is related. Everyplace I’ve been I have checked on Lowensons, but I can’t find very many connections. There are three or four that I have contacted that don’t seem to be related. But all the ones that were related disappeared because they stayed. They didn’t believe that it could happen and it happened.

Semler: They stayed too long. Tell me, what do you remember about your own growing up here? Where did you go to grade school?

LOWENSON: Well, I went to kindergarten, as I mentioned, at the Episcopal St. Helen’s Hall. My father, incidentally went to a school in San Francisco. My grandmother was too busy in the store (remember I said that she was always the merchant), that when the boys came by going to school, she took little Georgie out by the hand and said to the boys, “Take him to school.” So he kept coming home, day after day, and she would say, “How was school?” “Fine, but there is something funny about the school.” “What is funny about the school?” “I don’t know.” Finally he said, “All of the teachers there dress like ladies.” Well, they were taking him to the Catholic school. Well, she corrected that and got him into the public school. But his first three months in school were at a Catholic school. I don’t think it hurt him any. So that was how he started out. And I started out more or less the same way; I went to the school at St. Helen’s Hall. My mother tells me that I came home one day and I wanted to know what that guy had stickers on his head for. I got indoctrinated to the Jesus image, and I was told that there wasn’t anything the matter with him. I couldn’t figure out why he had to wear that crown of thorns, which I called stickers. So that’s where I started school. Then I went to Couch School, although it wasn’t in our area. We lived up on Main and Fifth Avenue; it was the closest school that I could get to decently. Most of the streets still weren’t paved.

Semler: Was Ainsworth School built at that time?

LOWENSON: Ainsworth was built. But it was very difficult to get there because there were no streets up there. You had to go up in the streetcar; it was the only way you could get up. The Vista Avenue Bridge had been built, but there was no road. There was a streetcar. There was a trail of a road, all mud. And until Vista Avenue development was completed, which was when I was in the fourth grade, which would be 1912, that is when I started at Ainsworth. Because you could get up there on the streetcar and I could walk home, or I could walk up because they put the streets in. So I went to Ainsworth and completed there. Then I went to Lincoln. Then I went to Stanford. Actually, I have only lived in three houses in my life. I lived in the one on Hoyt street, where I was born. I lived on the one on Main Street, which my father built in what had been a cherry orchard. I can remember this architect Schacht [?], who built for my dad. When my dad was in the real estate business, they bought vacant lots and built buildings on it and sold them. They didn’t operate them or anything. They did this on the side with whatever capital they had accumulated from the business. They called him the “president-maker”; he didn’t really make a president. They built one hotel and called it the Lincoln, and they built another one called the Grant. And two or three others. They had a penchant for calling them after the names of presidents. The hotels were not very presidential; they were pretty obscure.

Semler: Your father and your uncle did that with Mr. Schacht?

LOWENSON: They were always partners, my father and my uncle. Mr. Schacht was only the architect. He built our house, and he built my aunt’s house, and he built these buildings for them as an architect. He came from Europe as a German also. I don’t know what religion he was; I can’t remember identifying him as being a religion. But he came also to escape military service. Actually, he had a tendon cut in his finger, so he couldn’t pull a trigger. But in those days the German army was a very rigorous training for anyone, whether they were Jewish or not (that had nothing to do with it), and he didn’t want to go into the army. They went to any length to get out of army service. That is what Mr. Schacht did to get out; he cut the tendon in his finger. Most of them didn’t do anything as drastic as that. They just left Germany.

Semler: But military service was required?

LOWENSON: Yes. It was required here too for many periods. But not the same as then, mostly only during war times.

Semler: But that was required all the time?

LOWENSON: Sure. It is in Israel now. It is a common practice in countries all over the world. This is one of the few countries where it isn’t.

Semler: During the years that you were growing up, you said your grandmother belonged to Ahavai Shalom. Did she also belong to Beth Israel?

LOWENSON: Oh yes, she belonged to Beth Israel.

Semler: And how about your family?

LOWENSON: My mother and father, by the time they got married, Beth Israel was in existence, and so they joined Beth Israel right away. It was before Stephen Wise, who was that? Oh yes, Bloch was the rabbi. They were married in San Francisco. My mother was a very nervous person and very emotional all of her life. She got so emotional at her own wedding that she was married sitting down. I have a photograph somewhere of her wedding ceremony.

Semler: She couldn’t stand up [laughter]

LOWENSON: She couldn’t stand up. Then they came to Portland and joined Beth Israel. I went to Beth Israel Sunday school. It was called Reform. Then Jonah Wise came along, and neither Stephen Wise nor Jonah Wise believed in Bar Mitzvah. I don’t know where I ever got it from, because my family wasn’t very religious, but I wanted to be a Bar Mitzvah. So I insisted on it. There wasn’t any Hebrew School that we knew about, so Jonah taught me in his office. I went two or three times a week for a year; I had a year’s training. I think I exasperated him because Jonah wasn’t that kind of a teacher, but he did it. I always look back on my Bar Mitzvah as an outstanding event in my life, and I appreciate what he did to help me. I was also confirmed, which would have been, I guess, the following year. I was the first Bar Mitzvah at Beth Israel; no one had ever been Bar Mitzvahed at Beth Israel.

Semler: Were many people Bar Mitzvahed in that period after you?

LOWENSON: No. There were very few after me for quite a while. Not while Jonah was there, because he discouraged it. Maybe after that they began the Bar Mitzvahs. Neither Stephen nor Jonah, and apparently Bloch didn’t do it either. The Reform Movement was opposed to Bar Mitzvah. I don’t know how I ever got it into my head. And my son, Lee, wanted to be Bar Mitzvahed (he had that influence on his mother’s side, because her grandfather was a cantor, and you know Paula Lauterstein was a very religious woman) [according to Lee Lowenson, Paula’s father, Henry Nathan Heller, was a Rabbi in Berlin, Prague and Copenhagen. The Hellers immigrated to the US where Henry became Rabbi/Oberkantor at a synagogue in Oakland, CA. They came to Portland in 1907, and he became Rabbi at Neveh Zedek Talmud Torah]. I can understand that. My grandson, who now lives in Connecticut and has no connection, certainly not to Orthodoxy of any kind (on that side of the family they are not very religious), wanted to be Bar Mitzvahed. One of my two grandsons wanted to be Bar Mitzvahed, so he was Bar Mitzvahed; that was three years ago. I went back for his Bar Mitzvah. Somewhere the Jewish tradition leaks through. Even in California, one of my cousins there on the Hermann side had a daughter; the daughter was only half Jewish. I don’t know what happened (because we are not that close to that part of the family), but she went to Israel and lived there for a couple of years with a daughter. The daughter came back and was recently Bat Mitzvahed. That is very remote in San Francisco, or Oakland. We weren’t there.

Semler: So there is some strong Jewish feeling.

LOWENSON: There has to be.

Semler: Did you have a lot of Jewish friends or take part in Jewish activities during your teen years?

LOWENSON: Oh sure. I think the outstanding thing that we’ve missed here are the Jewish youth contacts. I don’t know what year it was started, I think it was about 1910. There was a Jewish social fraternity started in the east, by the name of Pi Tau Pi. Has anyone mentioned that to you?

Semler: I have heard of it.

LOWENSON: Pi Tau Pi became a national fraternity and was organized in Portland. I was the first one to be initiated in the original chapter. I think that was 1916; I was fourteen years old. The main people who organized it were Millard Rosenblatt (Dr. Millard Rosenblatt Sr.); Jerry Holzman, who wasn’t living in Portland then, but he sponsored it (he came over from Denver); and Oren Grossman (whose mother was a Mish).

Semler: Jerry Holzman was not Dr. Jerome Holzman?

LOWENSON: Yes he was. But he didn’t live in Portland then. At the time, he was in Denver, and that was where he got involved in Pi Tau Pi. I don’t know what he was doing in Denver. Maybe he was going to school; but he organized it. And Martin Sichel. But Levy, his family is since gone, and maybe one other. I was the first one who suffered through the initiation ceremony. It became a national fraternity with a lot of chapters, and it lasted until recently. We had social events; it was a social fraternity. We gave parties and only invited the Jewish girls. If it was somebody’s sister, she had to be invited through obligation [laughs]. Here are some old Pi Tau Pi things. This was corrected in 1926.

Semler: Is that a roster?

LOWENSON: No this is the constitution.

Semler: Do you remember some of the people who were members there?

LOWENSON: Well I named those. I was the first one who was taken in after the five organizers. Then Stanley Lang was a member. And Scott Sichel. Oh gosh, I could find an old roster, but I don’t remember anymore. There were other Jewish organizations. The Oregona Club. But it had no national affiliation. Jess Rich, George Wolf and Herbert Sichel had that group.

Semler: Was that also a social club?

LOWENSON: Yes it was, the Oregana Club. My dad was prominent in some social things. He didn’t do anything at the synagogue except support it (which he was always willing to do, whether he could afford it or not). But he was an early member of the Concordia Club.

Semler: Now that was a Jewish Club.

LOWENSON: Yes, a Jewish social club.

Semler: Who were some of the members of that?

LOWENSON: Oh my gosh. Julius Meier, old man Frank, Cecil Bauer; you would have to go into the archives. I have some records here we could probably look it up. This was my father’s generation. Then they came along in 1916 and organized Tualatin Country Club, which was a Jewish country club, still in existence. And my father was one of the organizers of that.

Semler: In those years there was a lot of Jewish social activity. Was there also a lot of social welfare activity?

LOWENSON: Well the big thing to start with (except for the “Abra Kadabra” society and things that were directly connected with the synagogue) was the Neighborhood House. It was the center of it all. And then the B’nai B’rith. But my family was never active in the B’nai B’rith. My dad was a member briefly.

Semler: Did you spend a lot of time at the Neighborhood House, or your mother?

LOWENSON: My mother was very active at the Neighborhood House. She taught cooking, and she took part in all of the activities there as a donator of services. Then for some reason or other, in about 1945, they needed some financial help at the end of the war. The building was badly run down. They put two men on the Neighborhood House board. One was the mayor’s secretary, I can’t remember his name, and the other was me. We didn’t have anything to say, but we had a lot of questions to answer, anytime the women had a question. We attended a lot of meetings regularly. I can remember Maureen Neuberger was on the board then and Grace Lang, Mrs. Berkowitz, amd Mrs. Hirsch. The building got so bad that one day the fire marshal came along and said, “Leland, if you don’t fix the fire escape – ten years ago we told you to put that in and you did, but it is on brick wall and there is no way to get on it –we are going to close you up. And the basement is a fire trap.” So I had an emergency meeting, and then I found out why I was on the board. They gave me a $2500 budget, and I was supposed to fix the building. Well, you couldn’t even fix the fire escape for that. They wanted to have the use of the building changed also; the cooking school had been housed upstairs.

Semler: Tell me what you did with your $2500 budget.

LOWENSON: Well I just about threw up my hands, but they said, “Well, you have to do it or they will close us up.” So I had a friend named Guy Jollevette. He is a good Catholic, and I had great confidence in him. He had done contracting work for me privately and in the store, and I knew that he had done some church work. He was a very soft-hearted fellow, so I worked on him every day. We both belonged to a club here in Portland, and I used to see him every day. Anyhow, I see him all the time, and I’d say, “Come on up. We’ve got to fix that building.” Finally, when we only had about thirty days to go, I got a hold of him one day after a luncheon meeting, and I said, “Jolly, you have got to go up there and tell me how we are going to get this thing done.” He said, “Well, I’ve just got my pickup truck. You wouldn’t want to ride in that.” And I said, “The heck I wouldn’t! We’ll go right now.” So we went up there at about 1:30 on a Thursday in 1945. I started to go through the building with him. I could see him; it was hopeless. The building was in terrible shape: The roof leaked; the downspouts were rusted out; the fire escape was out there, but you couldn’t get on it, and it was rusty. The basement was absolutely a shambles, apple crate construction down there. You couldn’t believe it. The fire door to the swimming pool in the new building was rusted so badly it was falling off. I knew the firemen would be back. The floor of the gymnasium was in very bad shape from the roof leaking; it was swelled and miserable. The furniture was terrible. Everything was terrible. All he could say was, “My, My.” He came downstairs, and I told him, “We’ve got to start on the fire escape. I have $2500. Go as far as you can.” Well he didn’t even want to start. It was a meeting of the Golden Age Club (do they still have that?)

Semler: I think they may.

LOWENSON: We hadn’t left yet. By this time it was maybe 3:00 or 3:30. The Golden Age Club began to come in. Now, as you may know, these are all people past 65 and 70 and into their 80s. They started in trying to play cards on this rickety furniture, and they had a drum and a violin and a piano, and they were trying to have a little dance. I could see Mr. Jollevette, and he almost fainted. He just melted; he had tears in his eyes. I looked at him, and I said, “What will we do?” He said, “I don’t know. Let me think about it.”

Nothing happened for about a month and then one day the secretary up at the Neighborhood House called me on the phone. I was at B______. She said, “There is this guy here by the name of something-or-another, and he wants to know where he should begin tearing out the office. Did you tell him to tear out the office?” I said, “I never told anyone to tear out any office. Who is he?” “He says he was sent up here and the contractor told him to tear out the office.” I said, “Let me talk to him.” And I said, “Who do you work for?” He said, “I work for “Emers and Jollevette.” So I said, “Well, if he authorized this, I don’t know what his plan is, but he knows what we need. You go ahead and get started.”

Well, in the next 60 days, they tore out all the partitions. They had a new steel door; they had a new roof; the floor was fixed; and the downspouts were fixed. The brick wall had been torn out, and the fire door put in so he could get out on the fire escape. The old kitchen was gone; there was a new, smaller kitchen that could be used, with modern conveniences in it, new linoleum on the floors, and new lighting fixtures. So, we never got a bill. Mr. Jollevette did that. I am sure he didn’t contribute all of that out of his own pocket, but he was a very successful contractor here, and he evidently put the bead on all of his subcontractors; somebody donated the painting, and somebody donated something else. We never knew. He did the whole darn thing. That is how it was done. Here was this strictly Jewish organization with all of these Catholic benefactors, which I think is a terrific story.

Semler: Yes it is. I have never heard that story before.

LOWENSON: That is how it happened. Through my lucky selection.

Semler: Through your being friends with Mr. Jollevette.

LOWENSON: The Greek Catholic church got into difficulties because it was built at the end of the war with some bad work by one of the subcontractors there. Mr. Jollevette, even though he wasn’t a Greek, went over there and saw that it was all corrected at no expense to anyone. We had the same problem at Beth Israel, with the Sunday school building that we built. The plaster was beginning to fall off. We paid for it. Our contractor never came to our rescue the way that Jolly did. This happened at the same time. The integrity of people, it doesn’t make any difference if they are Jewish or not, is always uppermost. You need fine people everywhere. I always wanted to do business with people with whom I didn’t have to write anything down. If you have to have your attorney write it, some other attorney is going to find where it was written wrong. But if you get a man’s word and he has high integrity (my father always lived on that basis, my [?] felt the same way, and I always have, and my children are the same way). I think Jews generally have. Everyone has people who fall off the values at times, but [??].

Semler: Leland, I’d like to go back and ask you one question. When were your parents married?

LOWENSON: They were married in 1900. They returned from their honeymoon and came up and went to the Hobart-Curtiss.

Semler: Education must have been very important to you because among your family and friends you had very good educations.

LOWENSON: My mother finished grammar school. My father finished the fourth grade.

Semler: Oh really?

LOWENSON: I think my uncle went further, but that was as far as my father went. He never liked organized anything. He belonged to the Concordia Club and the Tualatin Country Club and the congregation. He always supported the Chamber of Commerce, and he also supported everything financially, but he didn’t want to take any part in it. He was proud to have me go to college. He encouraged me and helped me go to Stanford. My father was more or less self-taught. He taught himself elementary arithmetic. He didn’t like the way they taught arithmetic; he showed me short-cut mathematics. My son is the same way. My son bought a computer. He wouldn’t even let the man that sold him the computer show him how to use it. He said, “Let me do it,” and he figured it out for himself.

Semler: So how come you got to Stanford?

LOWENSON: I don’t know. I wanted to go to Stanford, and I figured it out for myself.

Semler: Did it have something to do with being named after Stanford?

LOWENSON: Not that I know of, but it probably did. Wouldn’t you think? I heard that indoctrination from my mother’s friend Dr. Esther Rosencrantz, who worked at Stanford University and was in the first graduating class at Stanford. She imbued that into my mother, and I guess it was transmitted. It was a small college and a very good one. Because my family had lived in California all their life, in the San Francisco area, I had been down on the Stanford campus several times. I remember when my grandfather and my uncle went down to buy some cattle for the market. By that time they had an automobile; this would have been 1913 or so. They went down to San Jose to buy some cattle, and they took me down; we went to the Stanford campus. I was ten or eleven years old, and I was very impressed with it. I liked the way the campus looked. I even remember the name of the Italian we bought the cattle from in San Jose. His name was Apistopache.

Semler: Did many of your contemporaries go to college?

LOWENSON: Oh yes. By that time affluence had struck the American Jews, and they could afford to go to college.

Semler: The women too?

LOWENSON: Yes, the women, too. Esther Rosencrantz went to Stanford University; she was my mother’s contemporary. It was almost unheard of then. And to be a doctor! She graduated from Stanford and went on to University of California Medical School and then to Europe. When she came back to the United States, she was made president and manager of the San Francisco City and County Hospital, which was operated by the University of California. For them to do that for a Stanford graduate was really something.

Semler: And for a woman!

LOWENSON: And a woman. It was really quite something. We didn’t have women’s lib, but for a woman of merit, there was nothing holding her back. Many of them didn’t have a bent in that direction, because of the times. It wasn’t that they couldn’t or wouldn’t. It was just that they were not interested mostly. I guess raising families and the fact that lifestyles change. Everything has to change. We are never going to go back.

Semler: Tell me, did you know Celene more or less all your growing up years?

LOWENSON: The way I got acquainted with Celene. I knew Celene’s family because it was a big family down on the beach that lived in the big house on the block. But I never socialized with them. I just knew they were there.

Semler: What beach was that?

LOWENSON: Over at Long Beach.

Of course, my grandfather took my father down to the beach there when he was seven or eight years old. They used to go down on a boat to Ilwaco. The boat had to come in on the high tide because there was not dredging or anything, and there was only enough water at Ilwaco for a boat to come in at high tide. The boat would leave Portland, day or night, depending on the tide – so that it would arrive on the morning high tide, anywhere between five AM and noon. Then they had to get a wagon and go up the beach to the place they were going to camp. There were people there by the name of Baker and Stout (and others I can’t remember) that had campgrounds. They provided a platform, and my grandparents would come down with their own equipment. You had to bring everything: your blankets, your tent, your pots and pans, and whatever. They would land in Ilwaco, and then they would have to bid for a wagon. There was always more demand for wagons than there were wagons. So it was tough to get up the beach. Sometimes you would have to stay overnight, under very bad circumstances, to get a wagon. Because you had to go up the beach at low tide; there wasn’t any road. That was timed out carefully. So there were these platforms, and they had pumps there and outhouses. They wouldn’t go for less than a month, because you just couldn’t go through all that for less than a month. Then there was the very rigorous return home. And that was the vacation, when my grandmother rented the house down there. In 1894 (which was ten years after they came), they bought a little house, which we still have in the family. That is a pretty old house–1894. [Lee Lowenson notes that this date should be 1895]. I have all the tax bills. They bought it at a tax sale from some people by the name of Coffin from San Francisco. Why they ever came all the way up here and built a house, no one every knew. They evidently only occupied it for one summer. It was just a summer house. And they only paid the first tax bill; no, I don’t even think they paid the first tax bill. So my grandmother bought the house at a tax sale and paid them a quit-claim of some kind. I have all of those documents. I can remember going to the beach, and that is where I met Celene. I can remember going long before Celene was born, probably. When we were at the beach, the Indians used to come up, and they were with wagons; they would sell baskets and fish. That was really about all they had: baskets and fish. We bought some beautiful baskets. The fish are long since gone, and so are most of the baskets; we might have one or two left. We should have kept them; they were art pieces. My grandmother being the business woman of the group didn’t want to pay out any money if she could help it. She was a real trader. When the Indians came along, she would trade them a skirt or a blouse or a pot or a lamp. But they had to have some cash or they couldn’t get along either, so, at the final part of the trading, she would sweeten the pot with a little cash. But mostly it was trade. I can remember when those Indians came by, they didn’t speak much English, just a few words, and my grandmother would go out in front of the house. There wasn’t any road there, but by this time there was the railroad –not from Portland but from Ilwaco and later from Megler. I remember the first trip I made when I was probably five. We came into Ilwaco on the boat, and then the railroad took us up the beach.

Semler: So you don’t really remember the wagons?

LOWENSON: I don’t remember the wagons. They had the railroad by the time I went. But when my grandparents first came to California, the first trip they made, they came across the isthmus. It was that or come across the plains in a wagon. It was Tweedle Dee or Tweedle Dum; it was pretty bad either way. The information that they got was that an isthmus crossing was better, so one grandparent came across on the first railroad across the isthmus. By that time I think they had built a kind of a road so it wasn’t so bad. Then they went back to Europe for a year or two, and by the time they came back here the railroad went right into San Francisco. They came in on the Central Pacific, which was built by Leland Stanford.

Semler: That was where he made his money, wasn’t it? The Railroads?

LOWENSON: Probably. He was a rancher. He had thousands of acres, and the 12,000 acres that he donated to Stanford University was the Stanford Ranch. Stanford was called “The Farm” even when I was there. Many of the farm buildings were still there when I went to school. There was a huge 2-story barn that is still there; it is a part of their market. They still raised cattle; the race track was still there. The first motion pictures were made on that track at Stanford. A Frenchman came over and set up maybe 50 or 75 cameras with trips. They had threads going across the track every few feet. Stanford had a bet that when the horse galloped, all four feet were off the ground at once. The other guy in the bet said no. He had lots of money, so he brought this Frenchman over, and they set up this series of cameras (I think the pictures are down at Stanford yet). They had the horse run the track, and of course, every time he went over one of these triggers, it would trigger a camera, and sure enough one or two of the cameras got a picture of all of the feet off the ground.

Semler: So he won his bet.

LOWENSON: He won his bet. So this primitive time is almost within my memory. It is hard to believe that it developed so fast. In just one lifetime, and that I was fortunate enough to live during that period.

Semler: Now, you

LOWENSON: Then I met Celene here, through the clothing business. I was one of the organizers, with my father-in-law to be, Jake Lauterstein, of the Oregon Retail Clothiers and Furniture Association. We were not all Jewish by any means, but there were lots of Jews in this business. My father-in-law, I think, was the president at the time and he got me into it. The Nudelmans were members.

Semler: Do you remember about what year that was?

LOWENSON: I guess it was about…Celene could probably tell you as well as I can; I’ve got some records on that too if I could look it up. It was before I was married, and I’ve been married 45 years so I would say it was in the neighborhood of 50 years ago. Probably 1925 would be a very good guess. Or 1926. It was the first year that I came back here. They had also organized to have a retail committee for the Chamber of Commerce, and I got interested in that. Then we organized, and I was one of the original members of the Retail Trade Bureau, which was made a separate department of the Chamber of Commerce. Aaron Frank, Milton Gumpert, Julius Zell. I was the youngest of them. We threatened to pull out of the Chamber of Commerce if we couldn’t have an independent Retail Trade Bureau. You had to be a member of the chamber to be in it. Eddie Weinbaum was the first secretary. His salary was paid partly by the Retail Trade Bureau and partly by the Chamber because he was also secretary of the Trade and Commerce Commission at the time. That’s how we got that.

And that is how I met Celene. We went to a convention. One convention was at the Mork Hotel in Aberdeen; it was a Northwest Convention. The Spokane group came down, some from Boise, from Aberdeen, of course, and Olympia. Jake Lauterstein invited me to go along with Jordan. I’m sure it had nothing to do with Celene [laughs]. So he took Celene and me in the same car. Well, I was very much interested in Celene. There were some people by the name of Johnson (I can’t remember his first name anymore). We were intimate enough that before the convention was over they were calling her Mrs. Lowenson. And this was eight years before we were married. [laughing]

Semler: My goodness. Did you go together steadily for those eight years?

LOWENSON: We went more or less steadily for eight years.

Semler: That is a long time.

LOWENSON: I know it is a long time. The Depression came along. Then we went to a convention in Seattle, but by that time we were married; we went with Herb and Elise Sichel in Herb’s car. We also went to other conventions together. We got married in 1933, in the bottom of the Depression. By that time, I called Celene’s attention to the fact that we had nothing to lose because it was all lost. The only thing I could promise her was that we would never have less. [laughs]. So that was the situation when we got married. It worked out for us, and for most everybody else too, I guess. It will be 45 years this year.

Semler: And you have two children.

LOWENSON: We had just the two children. One is Lynn Marks. She lives in Connecticut. And Lee, who has been living for two and half years now in Kawai. He is not married, which I am very sorry about.

Semler: When was Lynn born?

LOWENSON: Lynn was born in 1935. She is the oldest.

Semler: And she has how many children?

LOWENSON: She has three children, Lianne is the oldest and is 16. Michael is 15, and Leland is 13. Lianne was confirmed, and Michael was confirmed and Bar Mitzvahed, and I guess Leland will be confirmed. That part of the family we see once or twice a year. She still likes to come out. They will be here in August. Lee will be here on his vacation in August, so we will all be together in that same old house down at the beach. My aunt practically gave it to me. My grandmother bought it for back taxes, and when Celene and I bought it in 1933, the taxes weren’t paid on the house. My aunt didn’t see any reason to pay the taxes, and about 1935, when Lynn was going to come along, my Aunt thought it would be nice to have the house for small children. It wasn’t much of a house; it was a poor house when it was built, and she didn’t have too much to do. Her two children had both bought a house down at the beach, a much better one. So she said her house would probably just go for taxes anyhow. She said, “If you pay off the back taxes and everything, I will deed the house to you.” So I gave her a nominal amount of money and paid off the back taxes, and we’ve owned it ever since. And then, a few years ago I hoped Lee would get married, and I gave the house to him. He has been handling it ever since. He has loved it. But now, since he has moved to Hawaii, I don’t know what will happen. But we still have it. He is a family man with no family, unfortunately. He likes the house, and he likes his family. He had his nephew over there last year, and he’ll have the other one over there in Kauai for a two-week vacation in Hawaii. He has a two-bedroom house; he uses one for an office. He is not in the clothing business; he is in the industrial supply business. The other is a spare room that he has for guests. He had his nephew there. And his mother and I are welcome any time that we want. We have been going over there twice a year. We certainly enjoy going. In the winter we go and see Lee, and in the summer we go see Lynn.

Semler: That is good thinking. When was Lee born?

LOWENSON: Lee was born two years later, in 1938.

Semler: Tell me, do you have any particular memories of the war years?

LOWENSON: Oh yes. In the First World War, I was too young. I helped win the war by working on farms. I picked strawberries, and I picked cherries and thinned apples and did that besides going to school. I worked for Wadhams & Co., who we had no relationship with at the time (with the Durkheimer family). I worked in the packing room after school and vacations and Saturdays. In fact, I was working there when the First World War ended. On Armistice Day, I can remember it yet. The plant shut down; it was on Fourth and Pine. Everyone got in our various trucks and things, and we went parading up and down town. I was in high school. I was working also for Lang Senders Candy Company. The war had come along and sugar disappeared. One of the things they had was a bunch of Riley’s Toffee, which they had imported from England, and which went bad on them because they couldn’t sell it fast enough.

Semler: Was this the First World War or the Second?

LOWENSON: First one, I was still in grammar school.

Semler: What did you do with the toffee?

LOWENSON: Well, it was all still wrapped; it had gone to sugar. They employed me to unwrap it piece by piece so it could be reconstituted and made into candy again. You can imagine what they paid me to unwrap tons of candy one piece at a time!

Semler: It must have been a tedious job.

LOWENSON: Yes it was. But they were having lots of trouble everywhere with food. Wadhams & Co. had some cornmeal go bad; a weevil got it. My first job I had with them was sifting cornmeal. I had to sift all the weevil out of the cornmeal so that it could be sold. Packaging and everything else they had were much more primitive in those days. Later I worked in the packing room there at Wadhams.

Semler: What about during the Second World War?

LOWENSON: By then I was too old. I was in business.

Semler: Do you remember anything about the community then?

LOWENSON: The only thing that I did. I was on the Home Guard again. I did the Home Guard patrols, fire patrols, and I worked on bond sales and Red Cross drives –all those kind of things. I don’t think I missed any of them.

Semler: Was there any particular activity within the Jewish community having anything to do with people who were in the Holocaust?

LOWENSON: There was a lot of activity. I think everybody…I have a sheaf of letters upstairs from various relatives and we. [TAPE ENDS]

LOWENSON: Our family in Europe had all done very well. Just as well as we had done here, and some of them had done much better. But when Hitler came along, they had to flee. That was why we found them. But we had been in touch with them. In 1925, when I was in Europe, I stayed with the family over there, but they were mostly in Berlin and also in Dresden; I visited Dansig and Cologne. I knew all of these people. There weren’t any in London yet. Then, when the Holocaust came along, they all knew us, and the first thing they did was write to us. We didn’t turn any of them down, but you couldn’t get them all out. In the first place, they wouldn’t let us sign any more than we could show financial responsibility for, and we had lots more relatives; we were just recently out of the Depression ourselves (and as I had said, the only thing I promised Celene was that I couldn’t have any less). So when we started to sign affidavits, they didn’t all go through. We did the best we could. A few of them did come over, and the ones that couldn’t, well we did whatever we could to see they could get out somewhere else. The Adams family, which was the biggest family, went to London. The Davidsohn family either disappeared, or the one that was in the Canary Island in Spain married there and moved to Mexico City. We have always been in touch ever since. And the one that anticipated all of it in about 1930, the smartest one, went to Stockholm. And we have visited them there. We have kept in touch with these people; none of them were ever a burden to us. Even the ones that we signed the affidavits for needed only a minimum of help. They all got out on their own, and they did quite well.

Semler: Tell me, how did the Adams family get to New Zealand?

LOWENSON: Well, that wasn’t the whole Adams family. One Adam went to London; they were fleeing. She had three sons and a daughter, and they all did well. In fact, Ken Adam got to be an art director in the movies. He did the London scenes for Around the World in 80 Days; he did all the James Bond movies and many others. Another son went into the steel business and did very well; he had branches all over. He died about two years ago. Dennis Adam was the youngest one. He went to New Zealand to go into the raincoat business, but he decided against that and went into the insurance business. He was the first insurance firm, and they called the firm Adam and Adam (Adam and Eve would come more naturally to me). Anyhow he had offices in [can’t hear all the cities he lists], Wellington, Auckland, Christchurch, …Australia and London. Of course, London has always been the insurance capital to the world. Probably through the family connections there he established that. But the main office is in Wellington. He has no children. The daughter is Lonnie. Her name is…. We visit with them in London every time we go, and I was in Berlin with them in 1925. It just happens that the present German government has offered any Jewish resident of Berlin a two-week free vacation in Berlin, any that would go. Many of them have felt so anti-German that they wouldn’t go. But Lilly Adam and her daughter Lonnie did take advantage of it in about 1973, and they happened to be in Berlin the same time that Celene and I were visiting Berlin, so we had a nice time with them there. They are the ones that told me about this, how they happened to be there.

I could remember from 1925 that the S. Adam Firm, which was on [struggles to remember street]. Anyway, it was a five-story building that had their store. They had a store like Abercrombie and Fitch. It was men’s and women’s, but not only apparel; it was mostly sporting goods. They manufactured raincoats. They had manufactured uniforms for the army in the First World War (that’s why the one son was going to go into the raincoat business in New Zealand). But that business collapsed when they had to flee. So when we were in Europe in 1973 and met Lilly Adam in Berlin, she asked, “Are you going to East Berlin to see the old store?” I said, “The old store must be gone. It is all bombed out.” She said, “No, if you go through Checkpoint Charlie, the very first corner you come to, it is all bombed out in the area, but that one building which was a very good building is still standing.” Sure enough, a few days later we went over, and there was the store (the store is long since gone, but there is something in there), the five-story building. I can remember it is very easily identified; it had bow-front show windows, which were unique. It was like at Broadway and Washington or 42nd and Broadway in New York with the heart (and I can remember it distinctly from 1925, and it is pretty pitiful to see it now). On the opposite corner was a little food store and a huge line of people were queued up outside. So I asked our East Berlin guide what they were standing in line for, and he said, “Oh, the people are so prosperous over here they are waiting to buy their food. There is more business for the stores than they can handle.” Well we subsequently found out that not only was there not more business than the store could handle, but there was more demand for food, and they were queued up everywhere. The first ones in would get the food, and by that time the store had disappeared. That was what was on what had been the most prominent corner of Berlin.

This Davidsohn – his father was in the hide business (lots of Jews seem to be in the cattle business or some part of it) in Dansig and also in Dresden. When my cousin Juan Davidsohn went to Spain, which had nothing to do with Hitler, he represented Bata shoes, which was a Czechoslovakian company (indirectly that is sort of the hide business too, shoes), and he represented them in all Spanish speaking countries and in Africa. He did very well. When Hitler came along, he couldn’t… the bottom fell out of the business. It was in Czechoslovakia, and the Germans overran it. So he had to look for another business, and he moved to Mexico City in 1938, where he still lives. He married a very fine woman there. He has visited us here. In fact, we have been in Europe with them only three years ago, and we went to British Columbia with them two years ago. We have kept in very close contact with all of these people all these years.

Semler: You really have. You have kept up a world-wide family that way.

LOWENSON: Well fortunately, my business in carrying imported and domestic dry goods all these years, it suited my business to travel. And in my business travels, I always included a vacation following. So London was an important buying market. Even in 1925, when I first started in the business, I did a little buying in Berlin–not very much because I didn’t have that important a position in the business. I went to the Leipzigger _____, which was the big Leipzig market, and I attended that because of my business interest.

Semler: When you were in Germany that early, did you have any feeling of what was to come?

LOWENSON: I didn’t have any feeling of any such thing, but when we visited these people in Cologne, which were on my mother’s side. Their name was Hirsch; that was her married name. She had been Hermann also. They were very religious Jews; they were the one branch of the family that was. They took me up to Bonn, up the Rhine for a day trip. It was like going on a picnic, except that it wasn’t a picnic. They had a young daughter; I think they had designs on me even then. Her name was Ilse. We still keep in touch. She is married and lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Anyway, we went up there. They had been so nice to me in Cologne that I wanted to take them to luncheon at the nicest place in Bonn. That was the jump-off place to go up into the mountains there, to the drachenfelds, where they have the orange festival in the fall. So I picked out the best place, and they said, “Oh, you don’t want to go in there.” And I said, “Isn’t this the nicest place in town?” and they said, “Yes, but you wouldn’t want to go in there.” And I said, “Why wouldn’t I want to go in there?” “Well look there!” And they had a swastika outside. And I said, “So what?” They said, “Would you go into a place with a swastika?” I said, “Why not?” and they said, “Well we won’t.” So we went to the next nicest place. And they said, “Don’t you know what the swastika is?” I said, “Yes, it is the Indian sign of good luck.” Which it was, on our Indian baskets they had a swastika, but it was made the other direction, which I didn’t recognize right away. So that was my first taste of it. That was in 1925, so there was some feeling already.

Semler: They were feeling it, but an outsider wouldn’t necessarily recognize it yet.

LOWENSON: When I was visiting the relatives in Berlin, most of them had been baptized. They didn’t deny they were Jews, but most of them had been baptized for business reasons. One of them was a movie director (the father of this guy who followed in the same line). The night I was there they had donated a pavilion to the Red White Tennis Club, and I sat at the head table because the family was being honored that night. And everybody knew they were baptized Jews, but there was no issue made of it in 1925. One member of the family on the Hermann side was a lawyer for the city of Berlin in 1925. He smelled a rat, and long about 1928, he moved to Sweden. So there were some people who knew. But if you remember the picture of the Holocaust that we saw recently, these things happened so gradually, and they are so appalling that people say, “It couldn’t happen here.” It is like what is happening to so many other countries right now that we see in the world, where we allow these people to take over. Like what is happening in Italy, and in Africa. These are the start of this kind of thing. It doesn’t involve Jews this time. It involves communists primarily. But you think these people won’t do the same thing to take over? We have been back to Prague twice, and I spoke to the few remaining Jews there (which is pretty sad, and although I helped them a little I am ashamed of myself because I should have done much more). It takes a few visits and closer contact before you can believe it. The Jews were not the only ones that suffered and not the only ones that resented these so-called Socialists. There are always people that take advantage of these situations and pin it on somebody.

Now the communists don’t pin it on the Jews especially. But when we were in Prague, we took a trip, and coming back on the bus (we were the only Jews on the bus that I know of), the bus driver said, “I want you to see this town. So we went down to Lidiche [?]. It was a town of 750 people. It was an industrial town, 100% Catholic. The bus driver took us out and showed us the monument, a huge field, maybe 300 acres, well kept up with the monument in the middle of it. He told us that this steel plant in the town was the only industry and this town had 750 Catholics and that was all that lived in the town. One of the people in this town had irritated the Nazis, and then another one had, and pretty soon some girl there had written a postcard complaining about the treatment that they were getting at the hands of the Nazis (now this has nothing to do with the Jews). The Nazis decided to wipe this town from the face of the earth (this is a story that this guide told us), to make an example for all of Czechoslovakia so that they would behave themselves. And one night they wiped out the town. Absolutely leveled the town and murdered men, women, and children except only the priest. The priest they said they would let go because he was a man of the cloth. And the priest said, “You murdered my whole flock, my reason for being here. If my flock is gone, you may as well kill me.” So they shot him. That kind of people. If the Jews aren’t the target, somebody else will be. Nothing you can do about it.