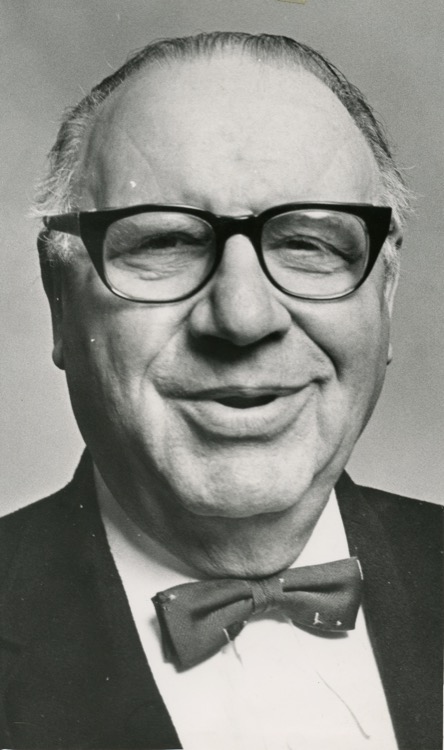

Julius Zell

1895-1976

Julius Zell was born in 1895 in Lemberg, a city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He had three brothers: Harry, Dan, and Milton. They had a half-sister, Rose, who had moved to the United States where she met and married Mike Silverman. Julius was eager to as well, and in 1909, at age 14, his father put him on a boat to the United States.

Julius arrived in New York City where the Hebrew Immigration Aid Society (HIAS) helped find him a job. So that he could attend night school, Julius held only day jobs, working in three different restaurants during the day and attending classes for two hours every night. His brother Harry joined him in 1911 and they moved to Portland, Oregon to be near their sister Rose. Julius worked for her husband Mike in his store, the Gem Jewelry Company, which sold glasses, suitcases, leather goods, and umbrellas. When Mike and Rose moved to Everett, Washington, Julius and Harry took over the store and renamed it Zell Brothers.

After the First World War, Julius traveled back to Lemberg to help his mother and two other brothers, Dan and Milton, move to the United States. As a result of the war, all of his family’s property had been confiscated, and his father died before he was able to return to Lemberg.

In 1917 Harry married Hanna Freudenstein, whom he had met three years earlier while visiting Rose and Mike in Everett. As a result of that union, Julius met Hanna’s sister Lillian. Julius and Lillian were married in 1922. They had two sons, Martin and Alan.

Julius was a member of the Concordia Club, B’nai B’rith, Beth Israel, Tualatin Golf Club, and was president of the Jeweler’s Association. He was also active in the Civic Theater and raised money for the United Jewish Appeal and the Jewish Community Center.

Interview(S):

Julius Zell - 1974

Interviewer: Janet Zell

Date: December 18, 1974

Transcribed By: Anne LeVant Prahl

Janet: [Please tell us] where you came from and your beginnings.

JULIUS: I came from Lemberg. It was then in the Austro-Hungarian Regime under Franz Joseph. During the First World War Lemberg was just like a football; first the Russians had it, then the Germans had it and so forth. But now it is back in Russian territory. It is the capital city of Austria-Hungary. It is the next largest city to Vienna. Only a night train ride away. In those days, people that would leave for America were only those who were practically destitute. They would save up just enough to get steerage fare to go to America. The head of the family would go and then they would bring the children and the wife and so on. My father was quite well-off. We had the finest beer agency in Europe. When I was about 14 years old, you could see the handwriting on the wall. I saw it. My father saw it.

Janet: About what year was this?

JULIUS: That was before 1910. I was born in 1895, you see. As far as advanced education, that is something that is practically unheard of for Jewish children unless you have political influence.

Janet: What kind of education did you have?

JULIUS: Well, just the lower grades, you see. And then you jump right from the lower grades to something like a Junior college and then to Gymnasium (not a gymnasium where you work out) where only a few, if any, are admitted. But with my father there would always be a private tutor and I was very hungry for education, anything I got a hold of I wanted to read.

Janet: Just for the record, do you want to tell me who else was in the family and what constituted the family?

JULIUS: Well, there was Harry. He is two years older than I am and Dan is two years younger. Milton was born about ten years later. I think he was the accident in the family.

Janet: So at the time you were about ready to come to the United States, Milton had already been born? The family was complete as we know it.

JULIUS: Yes, Milton was born. Father used to take me along on his trips. We had help in the house, the nurses, and we had two beautiful horses and one of the first hard rubber carriages. A fellow drove father around in the out-lying districts to attend his business. My love of horses was that every time I could I would throw a saddle on a horse, that was the first thing, even at midnight.

Janet: If things were so well financially for you, what made you want to come to the United States?

JULIUS: Father was married before. He was a widower. He had a very beautiful teenaged daughter. She was smitten with the boy next door whose father was a watchmaker. They were planning to go to America. They employed a tutor to teach them English and so on. And I got that bug. One time, when I was about 14 (I think I was Father’s favorite son – he was somewhat like me) he took me along [to meet] the mayor. My father was well liked and respected by both Jews and Gentiles, and that is very strange. He was one of twelve commissioners appointed by the Bergermeister, who was the mayor. He had something in mind. Father must have been past 50 at the time, or more than that, at the time he married my mother, you see. And he was asthmatic. I surmised that he took me along because he figured that someday I would be the head of the family and take over the business. And this I didn’t like. I finally confided in him that I don’t think there is a future for us four boys. Not only that, but to go into the army, which was hell for a Jewish boy, for three years. See there were two things that Jewish people used to worry about: When a girl got to be fourteen, they used to worry about marriage. When a boy got to be fourteen or fifteen, they worried that he would have to go to the army. There was automatic conscription.

So I told Father what I had in mind. I was a husky boy always, and full of ambition and full of life. My half-sister by that time was in the United States. She kept on writing letters asking, begging, because she was very fond of my mother, who had brought her up.

Janet: What was her married name, your sister?

JULIUS: Silverman.

Janet: Before that she went by the name of Zell and then she became [Silverman]? What was her first name?

JULIUS: Rose. Rose Silverman.

At one time, when she wrote these letters, we, all the children would write a post-script, and Father would write the letter. I wrote [her] to send me an English-German dictionary. I had this in my mind. But when Father brought this to Mother, she wouldn’t listen. “Oh”, she said, “Absolutely not!” So a few months later [inaudible], I saw what was happening to other youngsters and I said, “You don’t to have to tell Mother until I leave.” Money, that was no problem. Finally, Father said that he got me, through his political affiliations, entrance to the Gymnasium in Vienna. He was going to take me there. When we came there, they had tickets to go to Antwerp and a ship’s ticket, because it was Yom Kippur when we left. We both cried and when I got on the ship I realized: Here I am, not quite 15, going to the other end of the world. I was forlorn and homesick and lonesome. I cried for a solid year.

Janet: Were you going to be met by Rose Silverman?

JULIUS: No, she was already in Portland with her husband.

Janet: And your boat was coming directly into New York, is that it?

JULIUS: Yes, into New York. In New York, of course, they didn’t know until I wrote a letter from Antwerp, what I did. Father later on told Mother what was what. The boys didn’t know anything.

Janet: When was it you arrived in New York?

JULIUS: I left in 1910. I arrived in New York. Fortunately I had enough money to get better accommodations. Most of the immigrants came steerage, which is just like a cattle boat. I went first class. I had a nice voyage. When I came to New York there was a Jewish organization called HIAS, the Hebrew Immigration Aid Society. They meet you at Ellis Island, because first of all, there were two things you had to have when you got to New York. You can’t be illiterate. And those who were illiterate as far as the English language, they could speak Yiddish and German. Now I could speak fluent German, a little Yiddish, and enough English to make it work. And you have to have $100 minimum. Well, this I had. And some friend to vouch for you, or family, that you wouldn’t become a public charge. Well, I worked in New York.

Janet: Where did you find lodging?

JULIUS: I had a distant, distant relative on my mother’s side. They lived in a tenement house in a four-floor walk-up. To show you how they used to live, there were eight families on one floor and there was just one bathroom and one lavatory on each side of the hall. Now they had two children, a boy and a girl; this daughter was out here last year, I think you met her.

Janet: Where was the building located?

JULIUS: On the east side of New York. I was bewildered when I came there. It was something that I couldn’t comprehend – to see the busy streets and the pushcarts where they sold everything from shoelaces to clothing. They saw me coming, a little rosy-cheeked boy with a double-breasted suit (that was the style in Europe), and a wide-brimmed hat with the front turned up and the back turned down. I blushed to tears.

Whenever I go to New York, I send HIAS some money, because they have been so nice. Before they take you anyplace, you get a bath and you sleep for a couple of nights and they feed you. And then they follow up.

Janet: How are they funded?

JULIUS: They are funded by charity.

Janet: United Jewish Appeal?

JULIUS: This was before the United Jewish Appeal but it was a charitable organization. In those days immigration was so heavy that they had to have something.

Janet: Was it funded by the wealthy, New York German-Jewish families, do you think?

JULIUS: Well, I don’t know whether it was them, but I know it was funded by well-to-do Jewish families. In those days there was no such thing as government support for various organizations. HIAS don’t just bring you there and leave you there. They follow up. They come to see how you are getting along. A lot of [new immigrants] don’t get in a bad environment because some of these kids are hoodlums. As a matter of fact, the first day I sat in the park and they saw me, these kids playing basketball, they made fun of me. They started to bounce the ball right in my face. That didn’t do anything for my morale. I started to cry and the attendant came along and drove them away and I didn’t go there afterwards. But when HIAS followed up, they saw what kind of work you would like to do. I asked them, “What can I do? I don’t want to go to a factory.” When I hit New York, it was so distasteful. The living conditions compared to what I had at home (I had a palace compared to that), that I made up m mind to just stay long enough to see what’s what and then go back home. Get out of that place.

Janet: Was there a question of your going to school in the United States?

JULIUS: The first thing I did was that I asked to get a job where I could go to night school. I couldn’t go to day school because, you see, I have got to earn a living. I had to start in. So I got a job as a bus boy in a fine restaurant. That job I think paid something like five or six dollars a week.

Janet: Did this organization HIAS get that job for you?

JULIUS: Yes, they take you to an employment agency. That job was from 7:00am to 9:00pm. It is in Park Row, in the financial district. While you are not a waiter (I was a bus boy) you serve four waiters and these waiters give good tips because these Wall Street fellows come in for breakfast and discuss business and they sit there for an hour or two before they go to the office and they leave gratuities. Every waiter gives you 50 cents of his so from four waiters I had two dollars a day. That makes it lucrative. And then I got a job on the east side, at a kosher restaurant. At that time I was already a waiter because these people either speak Jewish or German or English. And I waited on them. They paid ten dollars a week for lunch. So this job was from 11:00am until 2:00pm. So I had two jobs, basically. Naturally, I had lunch so there was no question about food. And I had another job in the evening. I had to have a job that would allow me to go to night school. That was the first thing. I wanted to go to night school. And I had an easier time than a lot of immigrants because my German was fluent and I had enough English words in my vocabulary to make myself understood. I read nothing but English papers, unlike other newcomers who get the Forward or the German papers. And I didn’t allow anyone to speak anything but English to me. That is the only thing that I wanted.

Janet: Did your idea of America change or did you still have the idea that you wanted to go back?

JULIUS: Down there it was really hell in the winter time and the summer time. But I couldn’t write home and tell them. That wouldn’t do any good. You make a lot of friends there. There are societies and so on. I wanted to get enough money and to keep busy, so I got another job, from 5:30pm until 7:30pm in a restaurant that gave me also time to go to night school from 8:00pm to 10:00pm. So my day was pretty well occupied until I finally changed jobs because it was awful hard on your feet. I have ingrown toenails up to this day. I finally got one job in a restaurant on the West Side where the Rockefeller Center is, as a waiter. I worked there practically seven days. It’s in the Fur District. The furriers used to come down Saturday and Sunday.

Janet: How long did you keep up all these multiple jobs?

JULIUS: How long did I keep them up? I kept them up about a year and half. I kept on after but I got so that I saw that it was inevitable, I can’t do anything else. I kept on bombarding letters home, to Harry first. Then another year, Dan. Then Father got Dan into Gymnasium to “learn English as much as you can.” Then, of course, Milton was the baby.

Janet: Did Harry come and join you?

JULIUS: Harry came after in about a year’s time. In 1911. First Mother wouldn’t let him go so Father also saw that he came. He was too delicate for New York. He couldn’t take it. At home, through Father’s influence he got a job in an engineer’s office. It was a very affluent (not a Jewish organization) office. This engineer had the first Fiat automobile in the city. Harry used to go along with him. And he was a softy, a “Beau Brommell”. I saw that he couldn’t take it, and neither could I. So I started to correspond with Rose.

Janet: And she was in Portland already.

JULIUS: Yes. I finally arranged for Harry to go first. We thought that out west here there were Indians on the streets with hatchets. But after I came here I found out that the only wild Indians are in New York. I’ve never seen anything like it, until I opened my eyes and I came out to a civilized country.

Janet: So Harry came first?

JULIUS: Yes, Harry took the trip first and I said, “You come there and if you like, six months, if not, we’ll do something else.” But when he came here he found a good home. They didn’t have any children so they practically adopted him. Six months afterwards I picked up and left.

Janet: How did you come? By train?

JULIUS: I came by train. In those days the train from New York was over a week and there is no such thing as getting a Pullman. You have to sit up and sleep in the seats. And you bring along your own food. In my grip I put in some big salamis and bread. There was a lot of Polish and Russian and Finish people who used to travel on that train and they couldn’t go to the dining car because they didn’t have any money. I had enough knowledge of the Polish language so I fed them. I sold them a sandwich, for 50 cents a piece. When I set here in Portland, I said, “I still have a bologna left and I had about $40.” [laughs]

Janet: Now kind of lay the groundwork of what Portland was like when you first came. Where did you live and where did you start to work?

JULIUS: Portland was open. You didn’t see the buildings. Our store, Mike’s store, was right near the depot in the [unclear] Hotel.

Janet: When you say “Mike” who is that?

JULIUS: Mike. Mike Silverman.

Janet: He had a store already?

JULIUS: Yes, he had a store already. They had leather goods and suitcases – anything for traveling people because he was a newsagent and he saw that people had to go from one depot to another.

Janet: When you first came, did you live with him?

JULIUS: Yes.

Janet: And where were they living in the city?

JULIUS: Right where the new coliseum is, across the bridge.

Janet: So on the east side, like on Broadway and?

JULIUS: And Larabee. Right when you cross the bridge, right there on the corner. It was a four-flat; they fixed up a nice room for us. First, for transportation, I got a bicycle. I used to take Harry on the handlebars. The Broadway Bridge was just built.

Janet: So you would just bike across to the train station, to where the store was.

JULIUS: Right from there it was down hill. [laughter] And we worked there.

Janet: Do you know the name of that business? What was it called?

JULIUS: When he had it, it was the Gem Jewelry Company. They sold everything from drinking cups to suitcases and umbrellas. Half of the store was outside on the sidewalk. The suitcases that cost $3 in the store, they had marked for $2 outside. But you came in to get it. They were very happy to help you.

Janet: These men were already established at the time?

JULIUS: Oh yes. Ben Selling was Dr. Selling’s father, of the Selling Building. Julius Meier of Meier & Frank, Charlie Berg, who had a big shop, Charles F. Berg. There was always a helping hand, you see. As far as being charitable, you would find that some of the “newcomers,” (practically, like myself) they knew what it means to help another fellow. Some of the others, they forget about it already.

Janet: Now tell me a little bit, you mentioned the Concordia Club. Was the membership all Jewish?

JULIUS: All Jewish, the Concordia Club and mostly the Temple crowd, the Tualatin crowd. I used to belong there because I was a bridge player. It was no trouble for me. But then the old German Jews died off and there was no one else to keep it together, you see, so that was disintegrated.

Janet: I see.

JULIUS: Now, at the Tualatin Club, there are very few of the German Jews there. We’ve had one or two but they wouldn’t stay. They come to play golf but they dress in the car!

Janet: I’ve asked you before about the development of the store, about moving.

JULIUS: First we moved from Sixth Street to Fourth and Washington. Then after we established that store, we closed the other one, because we didn’t close one store until we could “cut the ice there.” And after we opened the Optical Department we had ambitions. Where Atiyah is now.

Janet: Yes, that is Tenth and…

JULIUS: Feldenheimer used to be there. It took some time to persuade Harry to go along.

Janet: At what time did you change the name?

JULIUS: When we took over in the 1920s, we changed the name to Zell Brothers.

Janet: So then you went from the Sixth Street location to Fourth and Washington. And after that you said it was Tenth and what?

JULIUS: No! Park and Washington. That is where Atiyah is, Park and Washington to Broadway and Morrison and from Broadway and Morrison up to here.

Janet: To Park and Morrison, yes. And each time you just kept the one store. For a while you had two and then you would close one.

JULIUS: We would keep two stores until we saw daylight.

Janet: Just for the chronology now, you opened the one on Fourth and Washington when?

JULIUS: 1920.

Janet: And that was the time also that you went to bring over the rest of the family.

JULIUS: No, it was after I brought the family. I first wanted to bring the family. We built a drugstore, next door to us on Sixth Street there. I bought a drug store.

Janet: The drug store plus the Zell Brothers store.

JULIUS: And then after the family came, I sold the drug store, you see. We kept it until things looked pretty good and then we closed the other store.

Janet: Where did the family live? How did you bring them over? Did you go over and personally escort them back?

JULIUS: Oh yes, sure.

Janet: How did you do that? Did you take a train?

JULIUS: No, we went first to Paris. And in Paris right after the war you couldn’t…

Janet: A boat to Paris? Or train across the country and then from New York. You took a train all the way across the country and then the boat across to…

JULIUS: Yes, to Paris. In France you had a heck of a time then, you couldn’t get out. What you can do is around the way through Germany.

Janet: And where was your family waiting for you? Back in Lemberg still?

JULIUS: Yes. They didn’t know when I was coming. Then my father passed away and I didn’t know because then I was on my way. You know Gene? His father went with me. He was going to meet his folks. He got married there. And in Paris, we were anxious to get out of there; we were three days in a cattle train. He went to Romania. I didn’t stick around to see whether or not he could get a train. There was a train going straight to Vienna. He went his way. He wouldn’t wait. He went to Zurich and when he came there some Jews got a hold of him and they promised him that they were going to get him a train out. He was there for ten days and they still didn’t get him out.

Janet: But you got to your family?

JULIUS: Oh yes, but I stayed and I finally got to the American Consul. One of the officers there, they had a very good spot and they gave it to me. So I had a sleeper, a two-day trip to Vienna. And when I came through Zurich at 3:00am, there was this guy staying. He couldn’t get on. I finally had to take him in my room and give him something. When I got home I found out that Father had passed away.

Janet: So it was your mother, and Dan, and Milton that were waiting for you to come. Did it take long to arrange it or were they just ready to come?

JULIUS: They were ready. After the war they confiscated their home. They had a beautiful home. They confiscated that. You couldn’t sell it but you had to leave everything there. They took what they had on their backs.

Janet: And your father’s business property. His carts and his horses?

JULIUS: Everything was integrated.

Janet: So there was no property to sell?

JULIUS: You couldn’t sell. As a matter of fact, if you had room, which we had, they moved somebody in and lived with you. And you couldn’t collect any rent.

Janet: So how long did you remain there to get the family out?

JULIUS: About a week is all.

Janet: And then you came to New York and across the country again. And you settled the family here in Portland.

JULIUS: And we had a home on the East side on Wielder Street, big enough for the family. And then we finally got a place on Tenth and College, because it was close to the shul for walking, and also close to night school. Mother went to night school and she got so that she could read and write.

Janet: Did she take her Americanization, too, or did she decide that she was too old?

JULIUS: No, no.

Janet: But you had to do that. Were you already an American citizen when you did that?

JULIUS: Of course. I couldn’t get an American passport unless I was a citizen.

Janet: And Harry, did he become an American citizen?

JULIUS: Yes, in 1919.

Janet: And then Milton and Dan. Now first you said that they went to Wielder; did you all live together? Did you move in again with your mother?

JULIUS: We still had our rooms in a hotel. We moved them to Wielder just to give them a place, you see. They were there for about three or four months and then we got a place on Tenth and College.

Janet: Now that is Portland State. So Milton and Dan lived with her there. Did they attend school?

JULIUS: Oh yes. Milton went to school. He was just 10 or 11 years old. Maybe 12. And Dan was about 18. He came right to me.

Janet: He went right into business.

JULIUS: And night school.

Janet: So then, by 1920 or ‘21 you had the whole thing. You had your mother and your brothers here. You had Dan working with you in the store and the store in 1920 was at what?

JULIUS: 1920, it was still on Sixth Street.

Janet: At the train station?

JULIUS: And at Fourth and Washington.

Janet: I see, so you still had the two stores then. You were at Fourth and Washington and Harry and Dan…

JULIUS: There was another man and Harry and Dan at Sixth Street.

Janet: Now, the idea that you were two young men in business in Portland. Was there a business association that you belonged to? You said other businessmen helped you. Did you have any problems? Some people have mentioned problems with labor, or the labor unions. Did you?

JULIUS: Not then, no.

Janet: No, this is still too early.

JULIUS: We had a watchmaker. But there was no such thing as a labor union then.

Janet: Then just really the effect of the family coming to Portland. You were going to tell me how you met your wife – how you met Lillian.

SECOND PART OF INTERVIEW several weeks later.

Janet: Tell me how you met your wife, married and your subsequent establishment of a home and family in Portland.

JULIUS: I met Lillian through the Neuberger family here. Our family lived in Everett, Washington, with the twins and Hanna. My half sister, Rose, moved to Everett, and Harry came to visit, and before you knew it, Harry fell head-over-heels in love with Hanna. She was the most beautiful girl I had ever met in my life. When he came back (we were in business then), he just went nuts. So I went back to Everett to see what’s what. Now Mrs. Freudenstein and Mrs. Lewis (that’s Ruth Neuberger’s mother), and Mrs. Stenger were sisters. So of course they saw a knowledgeable young fellow when Harry came there and they started to take the family here to do a little investigation. They saw not only one but two [possible matches]. With three daughters, you know, that means something, particularly with the Jewish people. I thought it is only in Europe that parents started to worry when a girl gets to be thirteen or fourteen, but with some of the older families, it happened the same here. Well, anyhow it takes two to make a match, three actually – a willing girl and a willing boy and particularly a willing mother-in-law. About three years later, 1917, the entire family went to Seattle, and Harry and Hanna were married in Seattle in the Sorretto Hotel.

Janet: And you were the only member of this family here at the time?

JULIUS: You see, we lost contact with our parents in 1914 when the war broke out, and there was no way to communicate with them. I was in hopes when I came here in 1910 to kind of helping the family over: Harry a year later, and then Dan who was younger and then Milton, of course, who was just a baby when I left home – and eventually it was three in the family to move to America. Then the war broke out. Mother would not have it. There were very few people of our standing that left for America, only those who were absolutely forced (we were comparatively well off) to go to America, to cross the ocean – you would drown.

Janet: After Harry was married in Seattle, did he bring Hanna back to Portland?

JULIUS: Oh yes, Harry married in Seattle, brought Hanna back to Portland, and they moved to the Rose Friend Apartments on Broadway and Jefferson – all owned by Rosenthal and Friendly; that’s Mel Friendly’s brother. When I came to Everett to investigate the two little snoozers (the twins as I called them) – they were only 14 or 15 – it happened that the three of them (including Hanna) had the same birthday, the 21st of the month. These girls, in those days, were reading these magazines and movies, and all they were visualizing were Rudolf Valentino, Wallace Reed – tall, dark and handsome. And they saw me as just the opposite, and they acted just like the rich man from far came, and the parents were going to trade their daughters to marry them off because they wanted to save the mortgage. They were reading too many novels. I gave them the cold shoulder. There were other girls in Everett and in Seattle that I used to take out. Poor Mrs. Freudenstein, she nearly went nuts. Anyhow, you couldn’t stop her. Mohammed said come to the mountain or the mountain will come to Mohammed, and she moved to Portland.

Janet: Where did she establish herself?

JULIUS: She moved to 14th and Jefferson. They had a big apartment. Hanna used to go to school here. She went to St. Helens Hall.

Janet: You mean she came from Everett, Washington to go to school here?

JULIUS: Yes, Hanna went to school here. As it happened, the Louis’, Mrs. Freudenstein’s sister, were very well off and they had only one girl, Ruth and a son, Dolf. Well, Dolf was the black sheep of the family, not the black sheep so much as that he did not agree with family tradition, but because he didn’t want his sister to marry this dumb Dutchman, Neuberger, that was his name. So they found out that he wants to live with Mrs. Freudenstein, and they took Hanna here. Hanna went to school here for two or three years. But [my brother] Harry didn’t know her until he came to Everett, you see. Hanna was so beautiful; they took snapshots, the drugstores had enlargements of her, full life-sized enlargements in the windows.

Janet: That’s nice. After Mrs. Freudenstein moved here to Portland with the twins, Hanna and Harry were already married; at what point were you and Lillian married? I don’t even know when you were married!

JULIUS: I was married about 1922. I went to Europe in 1919 to bring the rest of the family back. That was the first time we established contact with the family. My father was very asthmatic, and they kind of decided it was too late in life to come to America. They would live out their life in Europe but to get Dan and Milton over here. When I left Europe I didn’t know that probably I would never see my father again. So I decided to go to Europe and persuade them and make it easier for father to come here. When I was on my way to Europe, I was in Paris at that time waiting, because I couldn’t get any trains out; I was in Paris two weeks; meantime my father passed away. When I came home I didn’t know that my father passed away, so naturally I had to persuade mother too, because she had family there and she thought moving was something awful to think about. So I brought mother and the boys over here. The first thing we do was to enroll them in school, and to get them a place to live in. They had to have two or three bedrooms, so we got them a place on the East side, but mother had to live some place close to the synagogue and in those days there was nothing just walking distance, so we finally bought a little place on SW Fifth and College for mother, so she can go to shul.

Janet: You weren’t married then. Did you move in with your mother? Or did you keep your own establishment?

JULIUS: No, I lived in the hotel. Mother went to night school and learned to read and write and converse in English. I made it my business just to converse in English.

Janet: How long did she live after she came here? She came in 1920 and when did she die?

JULIUS: She died about 1935.

Janet: She had 15 years here. She lived to see Marty and Alan born, your mother.

JULIUS: She must have.

Janet: Then you married Lillian, so you got your family settled, and then you decided to marry.

JULIUS: Here is what happened. When I went to Europe, Mrs. Freudenstein, she had her cap set. She had a big apartment, about six or seven rooms. On one side was a separate entrance and since I was going to be gone a month or so, I moved in there. When Lillian grew a little older and so on, I was considered a pretty good catch, because at that time I was pretty sophisticated, a man about town and much older than age and years. So naturally she looked around, and there wasn’t any better bargain. My mother was very Orthodox and very superstitious as far as two brothers marrying two sisters. Well, this is the old Jewish tradition. As far as I was concerned, I thought it’s a method because you only get one mother-in-law. One Thursday night, it was snowing and I took Lillian out to a show and out of the clear sky I said, “You go and take the train to Seattle and I will meet you there tomorrow. Meantime I will get a license and on Friday we will get married.” But no one was supposed to know. They did not miss me in the store because many a Saturday night I was out to the Turkish baths and I didn’t get to the store until late. So they didn’t miss that I took a diamond ring out of the window. Ben Markman was my best man in Seattle. We got married. I called them up here and they were with mixed emotions. However, on Sunday, the entire family, Harry and Hanna and the others came to Seattle and we had a…

Janet: They came up to. So when was it? 1922 you said. What month?

JULIUS: It was around this time of the year, because it was snowing. [February].

Janet: So then you were married and you came back to Portland, and you took a honeymoon.

JULIUS: Then we came back, and we invited all our friends. That’s it.

Janet: It’s a fait accompli.

JULIUS: Yes, it was accompli. I remember just like today. I saw an ad in the paper to get furniture, you know. We had to look for something; we needed every penny. I saw an ad in the paper for some straw furniture.

Janet: Rattan.

JULIUS: Yes. We found just like a full apartment, a dining room set, a living room set, even a bedroom set, the entire thing. All of the furniture at that time we bought it for $350, we furnished a home.

Janet: Where did you live?

JULIUS: We moved to an apartment on the East side, and of course after Martin was born, we had to have a larger apartment, so we moved to 28th and Brazee, that’s where both Martin and Alan were born.

Janet: Then from what I remember your next move was to 1717 Montgomery?

JULIUS: That must have been ten years later that we bought the home on Montgomery.

Janet: Covering the time between your marriage and up till you moved to Montgomery, let me ask you about your activities. Were most of your energies in developing the store?

JULIUS: Not only in the store, you see. I was always hungry for knowledge, learning. As a matter of fact, when I first came to New York, I never allowed myself to speak German. I tried to converse in English and read the English papers and so on. When I came to New York I went to night school, and when I came here I went to night school. And of course when Milton came, he was about 10 or 12 years old, we enrolled him in school immediately.

Janet: But I was thinking now in the ‘20s and in the ‘30s, you were at that time married, had a young family, you were between 25 and 35 years old.

JULIUS: I was born in 1895. I was 27 you see, in 1922. We went into business, as I probably mentioned to you, by buying out Mike, who was Rose’s husband. We used to sell glasses at that time; we found it a profitable item, and I was looking around if I could go to school some place so that I could become a doctor or a pharmacist, but that required a high school diploma or an equivalent, and I knew that I had to pass an examination for a high school, or they wouldn’t accept me in the College of Optometry.

Janet: What was it called, Kaiser?

JULIUS: De Kaiser. I went for two hours in the morning – a two-year course at the time: from 8:00 to 10:00 in the morning and from 8:00 to 10:00 in the evening. I was fortunate to engage some high school teachers to cram as much knowledge into me because I had to pass an examination, but they accepted me on the premise that I will have the [high school diploma] equivalent; in other words, I did not lose any time, because in two years time while I studied optometry, I also picked up my credits; then I finally passed the board which was more than being elected president of the United States. There was no comparison to the way I felt then. Of course that proved to be the nucleus and a profitable part of our business, a stepping-stone from one place to another. But the main thing is that there were so many Jewish people in Portland when I came here in 1910. When a newcomer came to Portland he had no trouble in getting acquainted with Jewish people. It all depends where you lived. If you want to live in South Portland, which was entirely practically a ghetto, well then you found this type of people. But naturally we lived on the east side with Mike until he left town. So the main thing is that you got to belong; everybody wants to belong.

Janet: That’s what I want to know.

JULIUS: The first thing was joining the Temple, joining the B’nai B’rith, the Jewish Community Center, which was at the time on 13th Street.

Janet: You mentioned before the Concordia Club.

JULIUS: The Concordia Club was a social club for card playing, mostly the members of the Temple; they were very snobby you know, these German Jews. They were practically isolated. They wanted to be isolated. I had no trouble. Of course, Tualatin Club was for golf, and in those days, who had time to play golf? But I used to play golf when I first got married; I used to go out on the Municipal Court at five o’clock in the morning and play 18 holes of golf before I go to work. And on Sundays.

Janet: So the people that you chose to be with – I know some of your friends today – they were the same ones then?

JULIUS: You meet people of every description. I had no trouble making friends, you see. And all during my life, if you sit there you are a wallflower, but the minute you have an opinion of your own, and the subject is controversial and you express your opinion, then the first thing you know, you have got something. It happens the same thing with Temple Beth Israel.

Janet: I know that you always had the energy and you had the ability to do things. Once you thought there was a solution you did become active in these things.

JULIUS: I became active in every endeavor you see. In business we immediately joined the Advertising Club, the Chamber of Commerce and you get a diversified acquaintanceship, whether you look for it or not. The thing that impressed me most about some of the fine Jews of Portland, the real people that were worthwhile were old timers like Ben Selling.

Janet: People do mention him. Did you have a personal contact with him as to the way he helped people and what he did for people?

JULIUS: Oh yes. Let me tell you. I used to avail myself to getting advice from some people that were experienced in the same thing that I am doing now. Ben Selling was the Jewish leader in this town, and there was Dave Robinson who was the head of the Anti-Defamation League here for years, a very fine lawyer too. And there were others who thought that they had to crusade and protect Jews when they got in trouble. Like when a Jew in South Portland sold wine to a policeman which was sacramental wine, instead of pleading guilty (“I didn’t know that he wasn’t Jewish”) and pay $5 fine, there will be some self-appointed public defender who comes on. But Ben Selling and others will prosecute some of the bad elements in the city. In those days practically 80% of the prostitutes and the madams were Jewish.

Janet: Really?

JULIUS: There wasn’t a rooming house from around Second and Burnside to the depot, or from Sixth and Fifth to the depot that wasn’t run by a madam of our faith, and every one of them had a pimp hustling business for them.

Janet: A Jewish pimp?

JULIUS: Yes, sure. I’ll never forget the time when there was a big upheaval in the newspaper about the prostitution. Some of them used to rob people. Ben Selling and some of the other people had a committee. In later years, I was naturally part of the committee. They would hire a lawyer to help prosecute these people. They helped to clean up this area. We had a Jewish mayor by the name of Simon. Of course we had a Jewish governor, that was Julius Meier, but we did have a fine Jewish community here, particularly after some of these houses closed up, and the main thing is that instead of trying to protect the bad elements, they tried to prosecute them and get rid of them.

Janet: I noticed in reading your autobiography, you mentioned about the growth of Zell Bros., and as a Jewish merchant in Portland you had extended your contacts. Did you find that the community was open to you and not discriminating?

JULIUS: Nobody is trying to stop you in trying to advance yourself. In other words, it wasn’t so much the Jewish community. I had trouble with the optometric examination, which was 99% non-Jewish, because they didn’t want any competition from anyone they could see had a little push to him. But as far as the Jewish people are concerned, Henry Ford once said, “There is no such thing as luck, the main thing is pluck, but you have to waive the ’p’ and make it luck.”

Janet: I didn’t mean would the Jewish community accept you. Did the business community [accept you], which was probably mostly Christian?

JULIUS: I never felt any antisemitism as a whole during my early years, although sometimes you hear “dirty Jew” or something. It just passes up, because as far as that kind of a remark, we heard these remarks when I was a kid, not only that but with a stick. In 1920, after I brought the family over here, and I had built up my practice of optometry, I saw a vision that this would be a nucleus of something and I started to persuade Harry to move some place further, but he was satisfied with the status quo. You set your sights when you see some of these beautiful stores. We had some other fine jewelry stores in Portland.

Janet: What were some of the names of the other jewelry stores?

JULIUS: They had the Feldenheimers; of course, they were the Tiffanys. Then the Friedlanders, but not the Seattle Friedlanders. This Friedlander was second generation; he really could have been a lawyer, but his father was a jeweler and he was a musician. He had a very fine store. There was Felix Bloch, Staples, Jacob Bros. – they were all fine stores, you see, and most of them were not Jewish. The thing was this, when I found a location, a stepping stone, on Fourth and Washington in 1920, and I started to persuade Harry, and he wouldn’t see it, so I had to take the bull by the horn, and finally I threatened him and I said, “You can keep your jewelry store. I can take my opticals and open a hole in the wall and do business there. It was just two years after the optical law went into effect. You know, before 1910, there was no such thing as optometrists.

The law was very weak. The ophthalmologists like Singer, and the AMA. were much against chiropractors and they put optometrists in the same class because they had a lucrative thing going for them; not only did they charge for the examination, but they also sold the glasses. The others that I helped with the [examination] papers, the Board passed them and they didn’t pass me. I threatened the Board with taking it to court, and they passed me on my practical work, doing the job, but they flunked me on my written work, and my written work was good, because the others passed on the same written work that I gave them. Now finally after the third time, they gave up the opposition, they saw that they had to do it.

Janet: So since you got your license nothing was really in your way.

JULIUS: Half of the optometrists in town, they gave their eyeteeth to be with me, Stenger and all of them. I threatened Harry, “You keep this and I go.” We had two horses, one of them was a gray horse and the other one was a racehorse and you can’t hitch them up together, you see, and he was always for the status quo. I bought a drug store; I had to do something all on my own. He was always on the fence or “no.” I bought a drugstore and sold it a year later after getting all my money out. I paid $10,500 and sold it for $15,000 – in those days it was like $150,000 – and this gave us additional working capital. Realizing that we were going to have Dan and Milton, I had to make room for them. The Zells were very adaptable. One thing about the Zells, they were natural born salesmen. It doesn’t make any difference, if you can sell doughnuts, you can sell railroad cars. If I had stayed in New York, I could have been a restaurant owner. I could have been an actor if I happened to be around there. I could have been a lawyer if I had the qualifications, but some are satisfied with the status quo and Harry was a status quo individual. But after we moved there, we didn’t give up the old store, until we saw daylight here. But in that optical department on Washington Street, if it hadn’t been for that we couldn’t have paid the rent. But things started to pick up, then we sold the place on Sixth Street and Harry and Dan came over here. Milton was still in school.

Janet: What made you move up to Park and Washington?

JULIUS: Well this was just a stepping-stone. Park and Washington was on the fringe of the business district. The business district in Portland started on Front Street. As a matter of fact, Feldenheimers were there. Of course, they had a larger store.

Janet: Now which one was that, the Feldenheimers used to be on SW Fourth and Washington.

JULIUS: Yes, they used to be.

Janet: And then you moved there.

JULIUS: I moved there and between them was Dan Marx, and they moved up further. You know, people kept on moving further.

Janet: And where did Feldenheimers go then?

JULIUS: They went to the Platt Building, where we eventually moved to, where Atiyeh is now.

Janet: Park and Washington.

JULIUS: They had the entire ground floor. When we came there, it gave me a chance to take care of the optical department. It got so lucrative with the dynamic advertising job that I had to get help and that’s why I asked Harry and Dan to come there. We had to hire another man because the jewelry department picked up. This reminded me like during the last war with Japan that the US Air force and the fighting unit they kept on hopping from one island to another, Okinawa, this and this. This was the fringe. This was where the business used to be 10 years ago, now it’s moved up. All the business moved up further on Washington Street, up until Park. So after a while, four or five years, I started to agitate again. When I found that Feldenheimer moved out of there, they moved to the Pittock block, just one block up, and they subdivided the store. So I got the idea that we ought to get up into the swing and of course it took a lot of persuasion and a lot of decisions but we finally got there, but we didn’t close this store.

Janet: No, you always kept one.

JULIUS: We kept one until we saw daylight out there, you see. It is just as if the city was hungry for a shop like this. It was the most beautiful shop. It wasn’t any wider than this was long. It was a jewel of a store, with fine merchandise. Well, we hired Jerry Margolis and Alfred Stone; and Alfred Stone incidentally, his father was a jeweler and before 1890, they sold out to Feldenheimers and they were the leading jewelers in town.

Janet: Whatever happened with Feldenheimers? I know the name.

JULIUS: The Feldenheimers, they were very fine people. Albert and Charles Feldenheimer, they were two different types, like day and night. Albert Feldenheimer was a nice gentle individual. He used to call me J-u-l-i-u-s and his brother was something like Harry, tough. Well, they got along in years and they wanted to divest themselves. Charles Feldenheimer had one son, Albert Feldenheimer had two sons; one is still in town. He is 85 years old, Roy Feldenheimer, a very good friend of Sol Lewis, you see. Then there is Paul Feldenheimer who is much younger. They wanted to retire because they saw there was no one to follow them, you see, because Paul was very meek. Roy was interested in automobiles, a tinkerer. And the other one, Elmer, who was Charles’ son, had an orchard in Medford and they also had investments there. So they decided to quit, to go out of business and sell. That’s when they started to run an auction. I was president of the Jewelers Association and I had to stop them.

Janet: When they were ready to liquidate their business, you mean they were going to run an auction?

JULIUS: Yes. We put through a law, an ordinance that you cannot go out of business just by subterfuge. As long as the Feldenheimer’s name is going to be there, or their son, they are not going out of business. Their name was so good that we were afraid some high binder from the East, where there are a lot of them, would come out here and load up that store with their own merchandise, and put on a sale for three months and ruin the entire jewelry business in Portland. Not only that, if they remain, they see things are good, all they have to do is just use that name and milk it for a year or two. So we got through an ordinance, which was so drastic that they couldn’t live up to it. The program was so nice that they used to go with me to City Hall with other jewelers to stop others from running auctions. I am president of the association and it is my duty to do this. They finally had a street sale and they sold the assets and the name to his son, Paul Feldenheimer. That’s what they argued, “Inc.” is a different firm, but it’s the same family. They moved right there, you know where Miller’s jewelry store was on Alder and –

Janet: – and Broadway

JULIUS: Next door to it, he was there for 10 years, you see, as Paul Feldenheimer. Then we found out that Paul Feldenheimer was retiring, and their name was still good. You see he didn’t do any business to speak of. We were afraid that the same thing will happen, and then he came and he too wanted to run an auction, and we stopped him. I still have a copy of the bill of sale. He didn’t have $50,000 worth of merchandise in the store, and most of it leftovers from his father yet. But in order to protect ourselves, we sent in a real estate man to buy it. At that time there was a store vacant right across the street. Their lease was up, and all they had to do was to run an auction, and they have enough of money from that auction because their name was still good. That will ruin the business for three months before Christmas, and we were vulnerable because we were right on the opposite corner on Broadway and Morrison.

Janet: By that time you were on Broadway and Morrison. Feldenheimer was on Broadway and Alder. Yes, I see.

JULIUS: We had to make this sacrifice. We sent a man and he bought $5,000 worth of fixtures and their inventory, 100 cents to the dollar which after the war wasn’t worth 20 cents to the dollar.

Janet: So you bought out his inventory and everything?

JULIUS: He didn’t know who bought it, but he wanted to run just a straight sale for the holidays, which we allowed him and that’s how he sold us the name and everything. We never used his name but it also gave us a lot of lines, certain lines that we couldn’t get, they were exclusive there you see.

Janet: At what point did you realize that you, Zell Brothers, had become the most prominent store in town? For a while you said there were lots of them. At what time did you feel that you had reached the top?

JULIUS: When we moved up there we had a small store; it was a problem of whether we wanted to consolidate. The first thing, you know, it is beneficial to run a sale, but at that time we had good advertising, the finest advertising in the city – institutional advertising, Bob Smith – and proper aggression and a modern way of merchandising.

Janet: I have seen those ads.

JULIUS: It was so far out, so far ahead that they [other jewelers] were just like a bunch of runners. You saw them with 20 people running, and one would fall by the wayside; they didn’t fall by the wayside but they fell back, and as one falls back you get the lead.

Janet: Is there a point or a date, was it before the war? At what point could you say to yourself “we are it” because you are.

JULIUS: That was about when we moved up there with the small store; it was about 1925.

Janet: That was when you moved to Park and Washington?

JULIUS: But two years later we enlarged. We moved and consolidated the two stores. It is a funny thing what prestige will do, or credibility. We were debating as to whether to run a sale. We said we got to run a sale, a consolidation sale of both stores. Then we tried to justify running a sale in the new store where the consolidation is most reasonable, but we decided to run a sale just on SW Fourth and Washington Street. It was the same merchandise that we had up there. We increased our business considerably on Park and Washington, and we had a terrific sale for a month. In this store people bought merchandise, and you see we had this sale only on Fourth and Washington, store number one. People bought the same merchandise; they could buy it for 20% cheaper up there. When we enlarged the store, we more than tripled the size, and we opened the beautiful optical department. We were considered by everybody the top as far as a jewelry store in the city because there was Feldenheimers up there; there was still Tiffany’s, but they were just kind of deteriorating. As far as being considered the leading store in the city, they were it. They weren’t doing any business.

Janet: Did the Depression affect the store? History marches on.

JULIUS: The Depression hit in 1929. We didn’t feel the Depression for a year after everyone felt it, because we tightened our belts. I don’t think Harry and I drew over $100 a month. We cut down to a minimum the advertising and I got my work in the optical department. We kept on going and we didn’t feel it until much, much later, and then we kept our head above water all the time because we had a reserve. We had a good inventory to start with, you see. The Depression was just like now. It’s much easier to get yourself all built up with expenses, but try to get down to where you should be – just like a family. When a man makes $30,000 a year he gets used to living high. But when he cuts down to $15,000 a year, then it’s tough. In other words, I read it some place, when things get tough, if you don’t tighten your belt, you lose your pants.

Janet: That’s very good. You were telling us about the Depression.

JULIUS: Every landlord in the city gave their tenants relief as far as their rent is concerned rather than to let them go broke, but ours wasn’t much. We used to bank at the US National where our landlord, Mr. Pratt, a lawyer, was on the board. When I came to him, he said, “You are not bad off. I know you have a statement in the bank.” I said, “First of all, our statement is supposed to be confidential. You are not supposed to tell me that but you are a smart lawyer. Do you realize that if we took our markdown on what our merchandise is worth during the Depression instead of taking it all at cost? You know what would happen? We would go broke.” We couldn’t get a loan in the bank, you see. Anyhow, Durkheimers owned the building.

Janet: Was this the one on Park and Washington?

JULIUS: Yes, and they built the building on lease ground. They built it for Feldenheimers originally. To make a long story short, things fell into place. There is no use being a Jew unless you are a lucky Jew, and we were. We had a lease at $1275 a month, which had to run for another four years. Fortunately, the Durkheimers and the Platts were suing each other; they were foreclosing on the building because Platts were in arrears with the taxes, but Durkheimers advanced them the taxes $20,000, in order to pay their back taxes and penalty. Instead of paying the taxes, they bought a lot of bonds at depressed prices in order to get the control of the building. They were suing each other, and in the meantime we were fortunate to have in our lease that we are not responsible to any other landlord. Most leases read that in case the building is sold, the lease goes with it. This is what it stipulates, but this one here did not.

In the meantime, while they were suing, Platt said, “You [Durkheimer] want the building back; it’s your ground.” But he sued them for the amount that it cost to put up the building – smart lawyer. It’s just like a chain that breaks in the middle and we are the link. We fall out. I am not responsible to the new owner, which would have been Durkheimer. And Platt admitted that they don’t own the building anymore. So, a lucky break just came our way. Where Best is on Broadway and Morrison Street, that corner was used by Liebes, where Ungar’s is now. It used to be Liebes Fur – that is a San Francisco outfit like Magnin. But they were using the corner for the windows only for display because they had small windows on Broadway; they paid $3,000 a month. It was during the Depression just then. They gave it up, and when they gave it up, that building got on the market. When we found out that it was on the market – there were stores below that were vacant – we started to dicker with him. Well, we gave him a proposition on a percentage basis that ran up anything to a million dollars, we paid 10%. What the heck did we care about it, as long as the minimum is only $800 a month? If it was a Depression, we couldn’t have possibly had a chance to get that place, but who the dickens knew that by the time our lease would be up ten years from now, that we would be paying over $100,000 a year rent? We could have bought the building at the time, because they too were in arrears with the taxes. The insurance company wanted to move in. They made arrangements to give the owner $25,000 and sell out the building if we pay it out with the rent. At that time, $25,000 – we had to have every penny for inventory – and we were a little pioneer family in town, and I didn’t want my children in later years to come didn’t want to lose our inheritance for nothing. There were two reasons for it and good reasons.

Janet: That’s when you moved into Broadway and Morrison. What year was it when you actually got into that store?

JULIUS: It must have been right in the Depression. It must have been in late ‘30 or early ’31.

Janet: I would think so.

JULIUS: We had someone working in the store and we could have gotten along without him, because Harry and I and Dan could have run the old store, but I kept on working in the Optical Department. Jerry was a very good salesman. Stone was a very artistic individual and for window dressing – the finest. And also he was a social butterfly in town, and he knew everybody also in the gentile society – not so much in the Jewish society, which was an asset. But a funny thing that just when we moved to Broadway and Morrison – it was a beautiful store – did you ever see it?

Janet: Yes, I remember it because I visited in 1946 here.

JULIUS: And I also enlarged the optical department. In the meantime, while this was going on, I had optical departments in Olds & King’s and Lipman & Wolfe’s. When Milton graduated Optical School, I wanted him to get experience away from me because I am not an easy individual to teach my own. Strangers I can tell, “You do so and so.” It’s just like a husband can’t teach his wife to drive a car. While he doesn’t have the dynamic drive that I have, he had a certain easy-going personality that he took over the department and doubled the business in the first month. And by the time the year was up he was about eight times the amount, you see. I felt now that he is needed now back in the store. But in the meantime he had to go to war. I closed up Olds & King’s and Lipman’s, because I needed all the help, not only in my optical department. As it happens, I knew everything about the Jewelry store – bookkeeping, shipping, everything else, and I had to relieve myself of the extra part in the optical department by getting help, so that I could devote some of the time there. In other words, you see there are two ways in which you can do business. There were two executive types of individuals – Harry was an individual who had to do everything. It didn’t make any difference – to buy collar buttons – he had to be there. He wouldn’t delegate; he couldn’t. In other words, he made himself a gear in the machinery. When you are a gear in the machinery if that gear is taken out, the machine stops. My philosophy was to make yourself a switch. You put on the motor and let it run. As long as you can delegate and can overlook it.

The same break that we had to move out of the Platt building happened when Zukor bought the building because we were double-crossed. The real estate man knew what business we were doing. He told Zukor that our business is a gold mine, “Zells can’t move; they have all their investments here. It costs them a fortune to advertise.” And he offered $50,000 more for the building. We couldn’t run an auction with him. So we had three years to go. We had to prepare us a home. The difference about preparing yourself a home or a new store (we called it a home), if you have a small store you can get twenty, thirty small stores even where the location isn’t so good. But if you have a store like ours for which we use a second floor, and you want to expand, you have to pay through the nose. They have to have a building liquid. Another piece of the jigsaw puzzle fell into place. With Meier & Frank we had three years to go. How can we maneuver a new lease with them or find a location? We had to look for something. Meier & Frank’s at that time went public, the first time that they ceased to be Portland’s own store – they sold stock to the public. Bill Kernan, a superintendent there, and Rube Adams who was the merchandise man – as a matter of fact, Rube Adams married Ron Schmidt’s ex-wife. That was a hot stock and the employees, particularly the executive employees, got in on the ground floor, and they wanted to buy as much as they could. They owned the building where the jewelry store is now.

Janet: Park and Morrison?

Zell: Just half of it, not all of it. We called the realtor. We still must not let anyone know that we are looking for a store because I was still dickering with Zukor, and if anyone finds out what we are looking for, first of all the price goes up. I went to see Mr. Sims who was our realtor. Incidentally he was also in the Platt Building; he is still there. And I told him, “I want this on the q.t. We’ve got to find a place, a home. If we can ever get a location as good as Broadway and Morrison, but we got to be satisfied with quantity instead of quality.” We’ve got to get a little on the fringe because the space that we need, we couldn’t afford that much. I had my eyes on that little building because it was a nice little building with terra cotta, which we tore out entirely. So, I said, “Find out about this one here.” He said, “By Jove, I have got an idea.” So, he approached him and said (he didn’t say, “Do you want to sell it?”), “I understand this building is on the market, and I assume you might be interested because of Meier & Frank’s stock.” “Yes, we will sell it.”

$50,000 at that time was a terrific amount. I said, “Go back and tell him I think I can get more. Don’t tell him it’s me. I don’t want him to find out who it is, just tell him.” I had to coach him and teach him. I said, “Here, tell him ‘the more I get from you the more commission I get. So, you give me an option, 24 hours or 48 hours on $60,000. That’s $10,000 higher, so I can get more commission.’” There are a lot of people who want to make an investment. As a matter of fact some of them even think that it would be a good investment in Meier & Frank stock. So he came in, all written out to sell this for $60,000. “Don’t run right back, you got it in writing. You can wait until tomorrow.” I gave him a check for deposit, and that’s how we got the building. Then he told us many a times – at that time the building was worth $200,000 and with our tenancy it was worth much more. They knew that we needed it, and that we had to pay through the nose. Then, as a matter of fact, this street up there was so honky-tonky that we had to do everything to clean up the street. Gompertz were next door and they were paying very little rent, about $800 a month and all they can to not declare the percentage. In order to assure ourselves with a good neighbor – you see after we bought it, I tried to get Mrs. Gompertz to pay a rent that is moderate. I have the story here, the Gompertz story. On bad advice she lost her shirt moving away. Anyhow, for the other half of this building we only paid $50,000 and these people wanted $150,000 because it was longer. It was 50 x 150; this was 50 x 100 and they wanted more money. We got to have it. So we signed it in the same way. Let them give you an option otherwise they’ll run an option with you. They can go to someone and say, “I am offered by Zell $150,000. What are you giving?” So we signed $10,000 more. That’s how we acquired the other part of the building.

Janet: Now your activities as the “Mayor of Morrison Street”, that was part of the cleaning up?

JULIUS: That was part of the cleaning up. They were going to shoot me and sue me. I went around and saw that all the buildings were filthy, and I went and hired a truck with a steamer, and all I did was I cleaned up a round spot there. It was just like shaving a man’s head halfway.

Janet: One little clean spot…

JULIUS: They were marble fronts, but they were so dirty and filthy and everything. Well, they were going to sue. They were going to get a lawyer. They said you have no right trespassing. I said, “Fine. I want it. I suggest you get it and we will make a newspaper story out of it, and so on and so forth.” Well, they thought better of it. But it happened that they had to wash the balance of the building where Jaqueline’s used to be – Roberts Brothers owned that – and they covered it with marble and fixed it up nice – and then we had the Miracle Mile – if we did any business it would be a miracle!

Janet: These activities. Rather than being a gear, you wanted to be the one to press the button. Once the new store was built I know you did have time for other things. Perhaps you can tell me a little bit about the Civic Theater that I know you spent time on.

JULIUS: This was just mainly on the sidelines.

Janet: How did you get involved in the Civic Theatre?

JULIUS: I spoke at a Chamber or Forum luncheon once, and the director of the Civic Theater was there, and I have certain mannerisms which might be Jewish mannerisms, but certain individual mannerisms and expressions and throwing in a joke and so on and he was directing a play called The Late Mr. Bean – it was a play that had to do with a certain artist by the name of Bean who was a down-and-out guy who died. And like a lot of artists are not recognized until they die – like Cezanne – most of them, they struggle. He was keeping company with a woman and he lived in this family house. After he died they were cleaning his room and the attic and they found rolled-up paintings.

Janet: Did you play the role of Mr. Bean?

JULIUS: No. I was a connoisseur of art and I was trying to get these paintings and I was supposed to pretend that I was a great friend of Mr. Bean, that I hadn’t seen him in years, and due to his memory I would like to reward you for taking good care of them and so on.

Janet: Was that the first time that you had done a play or a theatrical production? Did you enjoy it?

JULIUS: Yes, I enjoyed it. Speaking for me in public was nothing. All you had to do was to have an opening and a closing; keep it short and clean. But you got to inject a little humor or it gets boring. When he heard me speak there he thought that I would just fill that thing here, and before I left he wanted me to come. I had the idea to read something about it. As I said, I could have been a lawyer because I used to go to the courthouse to listen to certain cases. He asked, “How big is the book?” Well, it isn’t just reading lines, but when you try to connive around to get these paintings away, you got to act in your mind. The more I read it, the more I started then to interpret it and so on.

Janet: About when was this? When was it that you first started?

JULIUS: There are so many verifications. It’s more than you can cover there.

Janet: I am thinking more of your activities. I know that the Civic Theater was one of them.

JULIUS: I was a good solicitor for money. I can go out for any effort; it doesn’t make any difference what it is, as long as I didn’t ask any favors for myself. I didn’t hesitate to approach anybody by using a certain strategy. You can and you can’t. You will and you won’t. You shall and you shan’t. You will not be damned if you do and you will be damned if you don’t. If you don’t, you will be just friends. In other words, try to put yourself in a position that they feel sorry for you. Go out and say, “I just walked my legs off, let me rest a little while!” A lot of times when they needed a chairman to raise money, right after Israel became a state; at that time we used to raise $50,000. At that time our quota was a half-a-million – something unheard of. Rabbi Berkowitz came in, and they just put the pressure on me and they put pressure on Lillian to put pressure on me and they put pressure on Harry. So they kept on persuading me.

Janet: This is the Bonds of Israel?

JULIUS: This is not the Bonds of Israel. This is the United Jewish Appeal – money for Israel, right after Israel became a state in 1947. I told the family, “This is going to be expensive because to go out and raise that kind of money we have got to be the leaders or close to it.” Because the speed of the ball is the speed of the game. I couldn’t go and ask anyone for $10,000 or $20,000 unless we were pledged before I go and as long as I said yes. I took it and we had a very successful drive. Not only that but I had to work just as hard in years afterwards with a new chairman. They didn’t get me into harness. I got myself into harness because I couldn’t be a part of a failure. I wasn’t a one-time shot.

Janet: More recently you used the same kind of enthusiasm and the same techniques in raising funds for the new Jewish Community Center, is that it?

JULIUS: But this is a different story entirely, it’s too rankly. If you want, I’ll give you another cassette on it. I’ll make you a notation at some time of some point that I left out. I’ll be able to give you a more coherent story. I hope you can make something of this one.