Jan Baross

b. 1943

Jan Baross was born on February 5, 1943 in Bakersfield, California; she had one brother, Dr. Thomas Meadoff. Her fatherDr. Nathan Meadoff was born in Gomel (now in Belarus) and came to the US as a young child. Her mother Estelle Kaplan Meadoff was born in Memphis, Tennessee. They metat UCLA. The household was a secular one, and Jan was permitted to stop going to Sunday school at a young age but the family continued to gather in Los Angeles for the High Holidays and Passover.

She graduated from Bakersfield High School and went on to a series of college experiences at San Francisco State, USC, Berkeley, and finally back to San Francisco. She studied art and became involved in student protests, where she met and married John Baross, a graduate student in marine microbiology. They moved to Corvallis, Oregon together in 1971 when John got a postdoctoral position there. Jan continued in school and received a masters degree in Media from Oregon State University.

Jan found work making films for the University, and found she had a talent for film making. She started making independent films and connected with the film society in Portland. In 1985, after divorcing from her husband, she moved to Portland and became an active member of the film community with Gus Van Sant, Will Vinton, Jim Blashfield, Joanna Priestley, and Joan Gratz, among others.

She pursued other arts as well, with an active play-writing, animation, and painting career. She spent half of each year in Portland and half in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where she is an active part of the arts community and the Jewish community of ex-pats in Mexico. In Portland she illustrated for the Jewish Review newspaper, completed a film on Oregon Jewish history, and has stayed involved in the arts and film making communities.

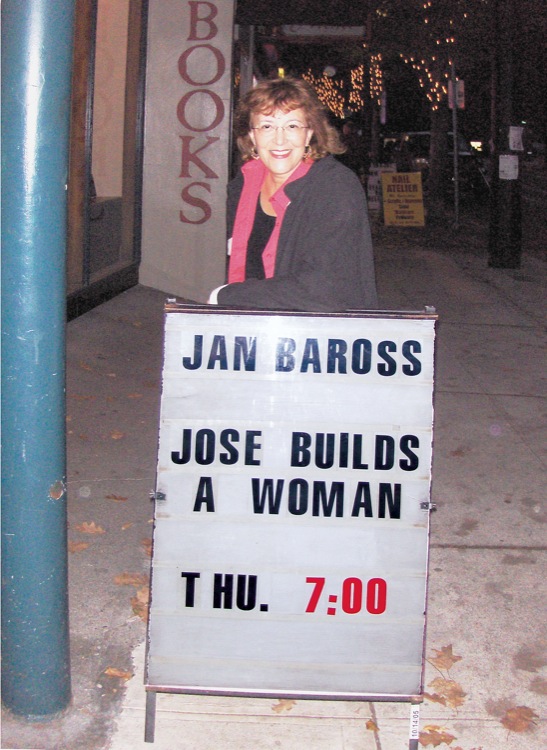

Many of Jan’s works of film are in the collection of the OJMCHE, as well as her first novel, Jose Builds a Woman.

Interview(S):

Jan Baross - 2017

Interviewer: Anne LeVant Prahl

Date: August 15, 2017

Transcribed By: Meg Larson

Prahl: Thank you for coming, and thanks for helping us make this record. I’d like you to start by stating your name for the recording, and where and when you were born.

BAROSS: Well, my real name is Wendy Jan Baross. I never use Wendy because the kids made fun of me at school, so it’s always Jan Baross. I was born February 5, 1943.

Prahl: Tell me a little about the household that you were born into. Who did you live with?

BAROSS: I lived with my parents in Bakersfield, California.

Prahl: Their names?

BAROSS: Dr. Nathan Meadoff and Estelle Meadoff. Her maiden name was Kaplan. She’s from Memphis, Tennessee, and my father was born in Gomel—well, now it’s Belarus.

Prahl: Your father was an immigrant. Do you know his immigration story? Do you know when he came to the US?

BAROSS: I know he came when he was about eight years old. I wish I had asked questions, of course, back then, but that’s all I know. They were in a ghetto. The Cossacks came and did wild things, his mother hid them in the attic, and they survived. Wait, I know a little more. Then his father came to this country but he got stopped by one of the wars, and he got stuck in Harbin, China, where he opened a little shop. Harbin, China, is very cool. If you look on the web it’s the place where everybody builds castles, real castles of ice, and gorgeous structures, and then lights it and makes it—it’s so cold you can do that, and it lasts for a season.

Prahl: Did you father live there, too, or just your grandfather?

BAROSS: No, just Dad. Then finally when he—whatever the war was that ended, he got to this country. I guess he must have come through Ellis Island. That’s about all I know except that they landed in Boyle Heights in Los Angeles where all the Jews were.

Prahl: But they came in through Ellis Island and then made their way across the country.

BAROSS: Yes, and Ma’s people were in Memphis, Tennessee, for some reason, and eventually they made it to Los Angeles. My mother and father met at UCLA. She was getting a master’s in social work and Dad was getting his—he was studying to be an orthopedic surgeon.

Prahl: Do you know what the work was that brought your grandfather to California? Do you know why he chose California?

BAROSS: No, I don’t know why. Nobody ever said. He just ended up there.

Prahl: So when you were growing up—let’s go back to the household you grew up in. Your dad was a surgeon then?

BAROSS: Yes.

Prahl: And your mom?

BAROSS: Well, Mom decided not to do social work. She stayed home with us. There’s a story about that. In Los Angeles, she was working in Watts. She was supposed to get people to support their old mother and father. She was in this one house and this man got so angry with her he picked up a knife in the kitchen and started chasing her around. He was going to kill her, so she jumped in the car and off she went and she was thinking, “Well, maybe this isn’t quite what I want to do.”

Prahl: Were you already born at that time?

BAROSS: I don’t think so, no.

Prahl: You mentioned “took care of us.” You have some siblings?

BAROSS: I have a brother. He became a doctor, ER. His name is Dr. Thomas Meadoff. Then he was killed in this weird car crash about three years ago.

Prahl: I’m sorry to hear that.

BAROSS: Thank you.

Prahl: Was it a Jewish home?

BAROSS: No, it was secular. Mom said that religion will destroy us all. It’s not anything I know you want to hear.

Prahl: I want to hear everything about your life. You can tell me anything.

BAROSS: Well, she’s always been very practical. She looked around and she saw, you know, the Holocaust, and then everything else that was going on, and she said, “It’s the religion that’s going to kill us all.” So, she didn’t want us to—well, she said, “Do you want to go to Jewish school?” This was in Bakersfield and there weren’t many Jews, but I said, “I’ll try it once.” I think I was about five or something, before you learned to read. Then they wanted us to learn the Hebrew alphabet and I didn’t want to spend my Saturdays and Sundays doing that. So I said, “Okay, that was it, thank you. No more, thank you.” That was the end of my Jewish education.

Prahl: Do you know how your dad felt about it?

BAROSS: He just kind of ignored it, I think. Not consciously ignored, he just went about his business being a doctor and Mom just wasn’t going to take us to temple or anything. It kind of got put by the—

Prahl: Had they experienced any antisemitism in Bakersfield, do you think?

BAROSS: Well, you’d think so, because it was Redneck Central, but no, not that much. The hardest thing was there were a number of orthopedic surgeons and they tried to keep Dad out, you know, from setting up a practice. He set up a clinic, he did very well, but he had to struggle against other doctors, kind of a jealousy thing. But I never experienced antisemitism. My friends, when I grew up, went to college. They said in San Francisco they experienced antisemitism, but I never did.

Prahl: Were your friends growing up mostly Jewish friends?

BAROSS: No. My best friend was Catholic. In high school before we’d go to a party she’d go and confess and then we’d go to the party, and then the next party she’d confess, then we’d go to another party. But that’s all I knew about Catholicism or religion. I guess I did have an education in the bible because we had this woman Lena who—mom wanted a maid, so she wanted a clean maid, so she got a Swedish maid from I think Arkansas or something. So she was kind of a fundamentalist person. So she would teach us about Jesus and God from a fundamentalist point of view. She would tell us about—she believed strongly that Jesus—I don’t know what she believed, but she told us bible stories and I really loved them, because she told them in such an exciting way, a fundamentalist and evangelical kind of enthusiasm.

Prahl: What kind of a student were you?

BAROSS: It depended. If I really loved something I got As. If I was bored, like with math, I got a C. So somewhere in between, maybe a B- student or something.

Prahl: Was it a country school, a city school?

BAROSS: Bakersfield High School. We had tons—I mean, that was a huge—thousands. Our graduating class was 800 people. It was a huge school. Then there was East Bakersfield, West, and Bakersfield High School. There were a lot of high schools.

Prahl: What were your activities outside of school?

BAROSS: The main thing I liked was drama club and tennis club. I was on the tennis team and I was in plays, but I liked to be behind the scenes. I just didn’t want that responsibility of having to really do a good job. It doesn’t matter what you do behind the scenes as long as everything is in its place, the props. So those were the two things I can think of.

Prahl: Did you grow up with an expectation from your parents about what you would do with your life?

BAROSS: Yes, I was supposed to marry a doctor. Need you ask?

Prahl: And your brother was supposed—

BAROSS: Supposed to be a doctor. So I married a PhD.

Prahl: That’s almost a doctor.

BAROSS: Well, I’m not sure my parents approved. They tried to get him to go to medical school, which was horribly insulting to him, but he didn’t pay any attention to them.

Prahl: That’s where the “Baross” comes from?

BAROSS: It’s Hungarian. John Allen Baross. When I met him he was studying for a degree. I met him in the Haight-Ashbury. We lived in the Haight-Ashbury. He was down below and our place was up above with the girls. He was down below with a bunch of boys. We invited them to a party one night. He walks in. Now, do you know Marcello Mastroeni? Picture that, only ramp it up about ten times. That’s what he looked like. So I said, “Okay, girls. I’m going to marry that one.” So I did.

Prahl: I think we have to get you to college before we get to how you met your husband. I was asking about your parents’ expectations for you. Did they want you to go to college?

BAROSS: Oh, no, there was no question about that.

Prahl: So they expected that you would just go straight to college?

BAROSS: Oh, yes, yes.

Prahl: Did they have suggestions or ideas about where that would be?

BAROSS: Well, I wanted to go to San Francisco State because that always seemed like the height of sophistication, San Francisco. But then I wasn’t too happy with it. It wasn’t a very beautiful campus, so I said, “I’m not really crazy about this place.” So they enrolled me in USC. But you know, that was really antisemitic. You know what they told me? The chancellor was all for Hitler. I mean, he had a picture of Hitler during the war, and the Jewish fraternity made him take it down. That’s the story I heard. Plus, here’s the Jewish sorority, here’s the Jewish fraternity, and people would go by at night and yell things at us. Can you believe that?

Prahl: This is the early ‘60s?

BAROSS: ’62. I couldn’t believe it. It was my first big Jewish antisemitic experience.

Prahl: One of the reasons you wanted to leave USC, or was it academics?

BAROSS: No, I was bored. I joined a sorority. I don’t know if you’ve done that but it’s—if you ever have a chance, don’t do it. It was just constraining, boring. I didn’t like the whole setup. I said, “This isn’t me.” So then I went to Berkeley in time for the free speech movement. I thought, “This is me.”

Prahl: You found your home. And what did you study while you were in school?

BAROSS: What was it? Art at USC, and then when I got to Berkeley I thought I should be intellectual so I changed to Art History, but I just thought the professors were—they were making up things about—well, I won’t get into all that, but anyway…

Prahl: Art History didn’t appeal to you.

BAROSS: No, so I got into “art” art. Then I was demonstrating for this free speech movement and I flunked out because I wasn’t going to class.

Prahl: Let’s talk a little bit about your political activism.

BAROSS: Well, not a big one. We were carrying signs. Joan Baez was singing, you know, the whole thing that you see on TV probably in documentaries, there we were. Free speech seemed like a good thing to fight for. One of the things I remember is, and this is kind of controversial because I was talking to a friend of mine. Mario Savio was the guy who was kind of in charge of the Free Speech Movement. He was one of these brilliant PhD program guys. I think he was a PhD. At any rate he was going for a degree and he was kind of in charge of that, intellectually. So I was standing next to him and there was a demonstration, and this kid runs up and says, “Mario, the Nazis are here. They’re going to set up a booth and they’re going to talk against us and the Free Speech Movement. Should we take them down?” And Mario said, “Well, we’re fighting for free speech, so they have a right to do that.” So that was a big lesson for me. It’s like, “Oh, we’ve got to put up with that.” Because now it’s the same thing. Nothing’s changed, right, with the Charlottesville thing? It’s kind of like free speech, but where’s the line? So I don’t know where the line is.

Prahl: Did you keep your political ideals when you left college?

BAROSS: I was against the Vietnam War and my parents weren’t. They hadn’t quite got there yet. They got there eventually but there was a tension between that—

Prahl: Was your brother the right age to go to Vietnam?

BAROSS: I think he was too young. There never seemed to be any worry about him, and if there was, I don’t know anything about that. He’s a year and a half younger. He was in college and at that time you could get married—he didn’t, but you could get married. There were ways to get out of it. Some friends of mine would drink a whole bunch of coffee grinds and a whole bunch of crap and then they would come in like this and they would get—not the word “expelled.” What is it you get? You get disqualified. There were all kinds of ways to get disqualified back then. You just abused yourself enough.

Prahl: Your parents were patriotic enough that they didn’t immediately say—

BAROSS: They sort of saw—finally they saw the handwriting on the wall. “Oh, yeah, this is ridiculous, let’s get out of here,” but it took a while for that generation, you know.

Prahl: What form did your being against the war take?

BAROSS: Well, demonstrations, joining I don’t what—well, that’s another thing. SNCC and CORE and all that, the black—Students Nonviolent something Committee. They were college things. Oh, that’s a national black organization. I’m not a huge activist. It’s just I was there, I was holding signs, and doing stuff.

Prahl: Were you still in college when you met your husband?

BAROSS: Yes, I flunked out, went to San Francisco from Berkeley, and went back to San Francisco State where I started, to finish up.

Prahl: You said you flunked out because you were demonstrating.

BAROSS: I know, it’s so stupid. Anyway, it was very passionate. I went to San Francisco State and finished up there. I was getting a teaching credential and that’s when we noticed the boys downstairs, so invited them over.

Prahl: Let’s try to move us toward Oregon. At what part of your life did you come to Oregon?

BAROSS: Well, I decided to marry this gorgeous man, so he didn’t have a chance. We got married and then I moved with him to Seattle, and then he got a post doc at Oregon State.

Prahl: What was he a PhD in?

BAROSS: Marine microbiology. Now he’s a marine astrobiologist, so he’s expanded into the universe, which is pretty cool.

Prahl: So it was his post doc that brought you to Oregon. What year was that?

BAROSS: That was ’71. We went to Corvallis. We were there from ’71 to about ’85 or something and then we got a divorce. Then I came to Portland, he stayed there. Now he’s at the University of Washington.

Prahl: Is he Jewish?

BAROSS: No, he’s Catholic.

Prahl: Was that ever an issue for you?

BAROSS: Well, kind of, because his mother was so Catholic and really a believer that she wanted us to get married in the Catholic Church. So I asked my grandma, I said, “Do you mind if I get married in a Catholic Church?” She says, “As long as you’re happy,” you know, that kind of thing. So I said, “Okay, I’m going to be very happy if I marry him.” So that was okay with her. And Mom said, “Just get married.” So we got married in a Catholic church but you had to spend I think it was a week or two with the priest to learn all about Catholicism.

Prahl: You can learn all about Catholicism in a week or two?

BAROSS: Yes, maybe a day! Whatever it was we had to take. I said, “I’m not going to do that.” But I wanted to get married to him. His mother is a lovely person and I wanted to please her, so I said okay. So we did that. So all I did was go in there. He was a young priest and all he talked about was his sailboat. So I thought, “I can deal with this.” So that’s what we talked about, his sailboat. And then he married us finally. He made me sign something that said I would raise the kids Catholic. I said, “Okay, I’m crossing my fingers.” He said, “I don’t care.” So I signed it like this, with my fingers crossed. I said, “Because I’m not raising them Catholic.” He said, “I don’t care.” Then he left the church after he married us and ran off with a nun on his sailboat and sailed off together. So I thought that was pretty romantic.

Prahl: Did you have any children?

BAROSS: No.

Prahl: Well, then, it didn’t come out to be a problem.

BAROSS: It was never a problem.

Prahl: When did you—or did you never stop identifying as Jewish your whole life? It wasn’t like you had a coming-back-to-being-Jewish feeling.

BAROSS: No, it’s just the feeling of always being Jewish, but it was nothing I pursued, other than every year Passover was with the family in Los Angeles and we ate a lot, and that was it. It was great. And we still do that.

Prahl: So even though your mother felt that Judaism, that the religion was going to kill you all, she still asked you if you wanted to go to Sunday school and she still participated in a Passover seder, but they didn’t belong to a synagogue themselves.

BAROSS: No.

Prahl: Did your dad speak English fluently?

BAROSS: Oh, yes.

Prahl: Did he have an accent?

BAROSS: No. The only way you’d know it is that every once in a while there’d be a word funny, with an “R” sound or something. You’d never know.

Prahl: Did he tell you stories about being a little kid in Europe?

BAROSS: No. I think he wanted to pretty much forget about that. We never heard a thing. He was just—both of them were just “let’s get on with it. We’re here, let’s make money and be comfortable, and I want to protect you.” He was really a good man, really kind and responsible. He had to not only take care of us but then the two grandmothers and the grandfathers who didn’t last that long, but it was an expense. Then he had a brother who hardly made any money at all because he wasn’t very bright, so then Dad put his son through college. So he took care of the extended family.

Prahl: Tell me what your sense of being Jewish was as a young woman. What form did it take or what did it mean in yourself when you thought you were Jewish?

BAROSS: Here’s something, here’s a story. I never thought about it one way or the other. No, I’ve got two stories. This is high school. My teacher who knew I was Jewish put up—he was always putting art up to introduce us clods to art. He put up one by—I can’t remember which Jewish painter it was—and he said, “Do you recognize that?” I said no, because it was abstract. He said, “It’s a rabbi.” He said, “I thought you would know—you would like that because you’re Jewish.” I thought—I didn’t even think about it. But then the bad story was, I guess it was going—Barry Goldwater. I forget what year that was but he was being nominated by the Republic convention, so a couple of us—I was with some kids who were very Jewish looking, black curly hair.

Prahl: ’64 maybe?

BAROSS: ’64. We were there with signs, with Barry Goldwater with a Hitler mustache. So we there and as people came out, I guess they could tell we were Jewish or something, but they were saying terrible things about Jews. That’s the first time I experienced anything like that.

Prahl: So experiences of antisemitism made you feel more Jewish.

BAROSS: Yes. It’s like, wow, this really is dangerous. When I was kid I always prefaced some of my questions like, “So, Mom, when the Nazis come again, are we going to do this and that?” So I was always aware about the Nazis and I always had dreams about Nazis, that I would sneak up behind them and shoot them, but then they would turn around and shoot me back. They were always a part of—that part, the violent part was always a part of my life.

Prahl: When you went through school and later in life, did you have friends who were Jewish, and did you feel differently toward them? Was there some sense of camaraderie?

BAROSS: Yes. I didn’t even think about it until a certain point where I thought: “Hmm, look at all of us, we’re Jewish.” I felt so comfortable with kind of the humor, the hard-edged humor. “They get it,” you know. Whereas when I moved to the Northwest and I’d do my humor, they wouldn’t get it. They would be insulted or “How can you say that?” “Wait, I’m kidding, this is Jewish humor.” So when I was with Jewish people, yes, much more comfortable in a way, you know? Not that it really matters, but there are certain things, certain ways of being.

Prahl: Has it affected your art in any way, do you think?

BAROSS: I don’t think so.

Prahl: Your art is just universal.

BAROSS: Yes, I would say so. I was trying to think if I ever did anything Jewish. Oh, yes, I did a film about Steven Lowenstein’s book. Before Steven died I said, “I think it should be a movie.” So he said, “Go ahead.” So I made a movie based on his book about being Jewish, because I thought the Jewish community would maybe—more likely kids would look at a movie than they would read a book.

Prahl: I have it right here.

BAROSS: So that’s the Jewish thing I did, I guess. I can’t think of anything else.

Prahl: Did that ground you a little bit in Oregon history? Did you know about Oregon history at the time you did that?

BAROSS: No, it’s fascinating.

Prahl: Let’s pick it up at coming with John, doing his post doc. What were you doing when you moved here?

BAROSS: To Oregon. Okay, Corvallis, Oregon, what was I doing? I got a master’s, that was it. I know I was doing something in school. I got a masters at OSU. I didn’t have much to do. It was pretty boring back then, I have to say. There wasn’t a lot of culture. So I thought, okay, I’ll get a master’s, my mother got one, what the heck, so I’ll get one, too. I got it in Media, and knew all the media people. Then I started working for the University making PSAs, 30-second commercials for the university, television commercials. Then I started working for the newspaper as a film reviewer. I was trying to keep myself occupied doing that. I was making films. Then I started making independent films then, too. That’s how I got connected to the film society up here in Portland. I started coming up. Then I got on the board, then eventually when I divorced Jack I came up here and I was a part of the film community here for a long time.

Prahl: Tell me about that, what you’ve done with the film community here.

BAROSS: I was on the board and we were setting up a co-op, taking films and showing them at old folks’ homes and finding venues for the films, Oregon films.

Prahl: Were they commercially-made films?

BAROSS: They were independent filmmakers like me, who went on to—like Gus Van Sant. I don’t know if you know him, Fight Club. He was kind of part of that and then Will Vinton and Jim Blashfield. Do you know these guys?

Prahl: Yes.

BAROSS: Joanna Priestley, Joan Gratz who got an Academy Award. They were all part of it.

Prahl: They were all in your co-op? What was the name of it?

BAROSS: I think it was just either Oregon Film Co-op or Northwest Film Co-op.

Prahl: Everybody was working on their own thing and then getting together to help distribute.

BAROSS: Yes, for distribution, for festivals, go down to Eugene, take our films and speak to audiences.

Prahl: I have to ask: What were you doing for money? That can’t have been very much money.

BAROSS: My father died when he was 54 which was in 1967 when I married Jack, and he left me enough to get by.

Prahl: You could make your films and not worry. That’s quite a blessing.

BAROSS: I know. I got paid, it’s just not a living for doing stuff, working on films, other people’s films and things.

Prahl: Now, I know you have other parts of your art, too, besides filmmaking. Do you want to talk about painting and other arts? Or did I skip over something?

BAROSS: My memory is so bad I’m just trying to remember what I did! Painting I did, but I’ve always done painting.

Prahl: Always? From high school, from childhood?

BAROSS: Yes, just always I was drawing on the walls, I was drawing everywhere. So, painting, and then I had some painting shows around town. I did photography and had some photography shows. Film things, then got into play writing and had some stuff in New York and L.A. and that kind of stuff, won some awards, and animation. Then I got into writing, so I wrote this novel, José Builds a Woman, and I did pretty well with that.

Prahl: I read it.

BAROSS: I was at your book group. That was so much fun. You have a good group. That was fun. I still remember that. So that’s what I’m still doing.

Prahl: You’re still writing.

BAROSS: I’m still writing, working on another novel.

Prahl: I want to keep pushing at the Jewish part. As you’ve aged in Portland, as you’ve grown here, have you sought out other Jews at all, or do you just meet people through your work and what you’re doing.

BAROSS: Well, I wanted to be more Jewish. It’s something—but my cousins are really Jewish, you know, and they do Rosh Hashanah and they do all the holidays.

Prahl: Where are they?

BAROSS: Seattle, Manhattan, Oklahoma, and Los Angeles, but they all come to Los Angeles where most of the family stayed.

Prahl: So most of your family gatherings are still down there?

BAROSS: Yes. In fact, I’m going to Rosh Hashanah. But I’ve never had that wonderful feeling that my cousins had, and I wish I had been raised where this stuff is really meaningful to me, but it’s not.

Prahl: Did you ever talk to your mother about it?

BAROSS: No. I mean, what is she going to say?

Prahl: She did what she thought was right.

BAROSS: Yes, that’s her. So I’ve tried. I took classes at the synagogues. What’s the name of the big one?

Prahl: Neveh Shalom.

BAROSS: Yes. So I’ve taken classes, and that was about it.

Prahl: How did you find them?

BAROSS: Well, I thought it was really interesting. The one I liked the best was—is that his name, Daniel?

Prahl: He’s just retired from Neveh Shalom, Daniel Isaak.

BAROSS: No kidding. I remember when he first got there. He was giving a class and he would take a bible story and he would deconstruct it, as though it were a play or something. We would talk about the characters and what they were doing.

Prahl: It must have been right up your alley.

BAROSS: I was fascinated by that. That was my favorite class. That kind of thing I thought, wow, no wonder it speaks to people. This really is basic, a basic human thing.

Prahl: Portland has a lot of adult education, doesn’t it?

BAROSS: It sure does. I know I don’t have much Jewish stuff to tell you.

Prahl: That’s fine. How about if we talk about Mexico?

BAROSS: Obviously the winters here are pretty rough so I started—and also when I divorced Jack—we used to have this huge Christmas. You can imagine, Catholic, five brothers and sisters and family and all that. Without that, it’s like, oh my God, and here’s this horrible winter, what’ll I do? So my mother had taken me down to San Miguel de Allende in Mexico and I thought, “This is a terrible place. Look at all these old people.” Then many years later a friend of mine said, “Come on down, this is great.” She was an artist, so I went down, and it was fantastic. So I thought, “This is where I’m going to spend my winters, and I’ll be happy.”

Prahl: Did you start out down there by taking some of the workshops that are offered, or just to go live?

BAROSS: No, just partied! It was great, took some Spanish classes. It was a wonderful town. It still is.

Prahl: About when was that, that when you started going?

BAROSS: About 30 years ago now.

Prahl: Every winter for 30 years?

BAROSS: Pretty much. Going down again. I’ve got a place that I rent, not the same place, but I go down and rent a place for about three months and then come back.

Prahl: You miss all the worst of the winter.

BAROSS: Also there are so many Jews down there. In fact, one of the largest Jewish families came over, set up a hardware store, and the guy had—I can’t remember his name but he had the dream of gargoyles and what he would do. So he made this wonderful structure with the gargoyles that he had in mind, and the Jewish star all over it. If you go there you’ll see the hardware store. Now it’s a mall but it was—with tiny little wonderful shops. You can buy this piece of candy or that. It’s really chichi. But they left the gargoyles and the Jewish star up above. Anyway, that family was there for three generations.

Prahl: Do you see the same people every year when you go? A lot of people who are doing what you’re doing?

BAROSS: Yes. There’s a woman in particular who set up the whole Jewish community there. One time she took us up to Mexico City to meet the Jewish community. It’s giant in Mexico City. The ambassador from Israel stayed in that community. It’s like a big fortress. It has to be a big fortress. They deal with it as though they’re in enemy territory, so in order to get in you really have to have a pass or something. We had to go through a bunch of stuff just to get inside to the party. It was a goodbye party to the ambassador.

Prahl: In San Miguel, when you say she put together the Jewish community, what kind of things does the Jewish community do there?

BAROSS: Now it’s huge. Every Friday and Saturday they have the ceremonies and the readings and the singing and the whole thing. It’s a much older community. Her name is Miranda and she organized us. She organized them, she organized us, and we’d take trips to different places as a Jewish community.

Prahl: Has being Jewish, do you think, influenced you in your art or your writing in any way?

BAROSS: I don’t know about that except that—well, maybe now because it’s a memoir. So I’m going back and looking at my whole life. There’s plenty of Jewish stuff in there because Mom has great funny things to say. Being Jewish in Redneck Central, there’s a certain amount of tension there which I’m going to exploit because I never really felt that somebody would come and kill me, not in Bakersfield, from the outside. I always thought the Nazis would come again.

Prahl: I’m struggling because most of my questions here are asking about the Portland Jewish community, and every time we talk about Judaism, your sense of being Jewish seems to be centered in Southern California more than up here, because that’s home. That’s where your family gets together.

BAROSS: Yes. We get together in Los Angeles. Most of them are dead. I made a film about the family, too, coming from Russia and that sort of thing. I don’t have a sense of Oregon Jewish-ness because—

Prahl: You made a film about your own family coming from Russia?

BAROSS: Yes. It’s a three-part series. The first one is called Happy Feet and it’s her life, but it also includes interviews with the whole family who came from Russia. Joe Cohn who was a friend in the old country used to carry the books because he wasn’t Jewish and they were.

Prahl: Who told you these stories?

BAROSS: Joe Cohn. He used to work for MGM. He was a big macher there.

Prahl: Did you go sit with him on purpose to get his stories from him, or were these just things he told you?

BAROSS: No. Mom and I went—I interviewed Joe, interviewed all—I told the whole family you get two minutes, come. So they all gathered at one of the families’ homes and I gave them all two minutes. One of them is a big ham. He was playing the piano. He was an accountant for people like Maurice Chevalier and stuff. They’re really colorful characters. It’s all about them coming from Russia and being here. It centers on Mom, and then that was Happy Feet. Then That Five Star Feeling is her life. After Dad died at a young age she moved to London, and she always felt that would be the most romantic thing, to live out of a suitcase and be a gypsy. So she moved to the Mayfair Hotel in London and she was there 30 years. The third part of the series, which I’m still interviewing her and other people is—she’s 103, I told you—so the last part of her life.

Prahl: Where is she living now?

BAROSS: Santa Barbara, in a hotel. So that’s the Jewish part. I don’t have a lot of Oregon Jewish thing other than taking classes and trying to be Jewish.

Prahl: That’s okay. We don’t have to make it fit.

BAROSS: I was just trying to think of anything else. Oh, I had some exhibits. Oh, yes, I had an exhibit when I went to Israel. I’ve made a lot of little books, sketches in books, so I did a bunch of sketches when I went to Israel and had a show up at the MJCC.

Prahl: What’s the name of that book?

BAROSS: Oh, I haven’t put it in a book yet, I just did the pictures.

Prahl: Part of the series of you traveling and sketching. The last question on this sheet is about

BAROSS: I just remembered something else. I used to work for the Jewish newspaper and do cartoons for them and articles.

Prahl: The Jewish Review? We have all the copies of The Jewish Review here. We’ll have to find some of them.

BAROSS: You don’t have to do all that. I have copies of the cartoons if you want.

Prahl: Those would be great to have. We would love to have them. The question is about the community in Oregon, and changes that you’ve seen in Oregon since you arrived here.

BAROSS: It doesn’t have anything to do with being Jewish. The biggest change of course is the traffic and more people, but more culture, too. I think it’s really exciting for kids, young people coming up because there’s so much to do here. The theater has gotten better. I’ve watched the theater get a lot better. I’m really interested in theater. I do cartoons for them, too.

Prahl: Which theater?

BAROSS: Artists Repertory Theatre and Portland Center Stage. I sketch their shows and then they can use it for Facebook and stuff. The level of sophistication has grown. Of course, the downside is all this building that’s going on. I don’t know what’s going to happen to this town. I don’t know what it’s going to be like in a while, if we can even get around.

Prahl: It’s overwhelming.

BAROSS: It is. Then I’ve watched us all grow old, the film community. I just was at a recent memorial for a past friend who wrote screenplays.

Prahl: Do you still keep in touch with the filmmakers that were in that co-operative?

BAROSS: Yes. Jim was there, Joanna Priestley, Joan Gratz. I don’t know if you know Eric Edwards? He was Gus’ cinematographer. Roger Margolis is a screenwriter. They teach over at Northwest Film. I don’t know if I mentioned, back in Mexico, screenwriting. I was working on a screenplay with a producer down there, but that’s not really relevant.

Prahl: Well, it’s part of your work life. Were there some things that you had hoped to talk about when you came in today? Certain stories that you particularly wanted to talk about?

BAROSS: Maybe it’s relevant. My mother couldn’t stand Bakersfield, so from the time I was 15 we were traveling all over the world, and one of the places we went was Israel in 1959. That wasn’t far from the starting of Israel, and it was really interesting to think back on Israel then, because it was just a backwater. You can imagine. There wasn’t anything fancy going on. I know you’ve seen pictures of it, or been there probably, right? Oh, my gosh.

Prahl: Were your parents Zionists?

BAROSS: No, my grandmother and her sisters were Zionists. They raised money to give to Israel so the Jews could buy the land in Israel. So they did that. I interviewed—what was her name? She was a Zionist, too, here in town when I was making the Jewish film. So cute. Not Ziggy. What was her name?

Prahl: You were just five years old when Israel became a state. Do you remember it?

BAROSS: I remember they came around with little metal blue things. Do you remember that?

Prahl: The Jewish National Fund.

BAROSS: Yes, so they would come around and Mom made me give them my allowance, which I have to say I resented. I had no idea why I was giving them my money, but I remember that blue box in my face, going, “Oh, fine, take my money.” I just forgot all about the travel thing, but we’ve been everywhere.

Prahl: Who is “we?”

BAROSS: Mom. I can’t connect it with anything Jewish but we’ve seen Europe, Asia, and Africa, back in ’59 when it was really what they were. Now, everything is us. I’m going to just see about anything Jewish. Gomel.

Prahl: I really want to hear about other things, too.

BAROSS: Okay. Well, I had a crush on a rabbi’s son in Bakersfield. He’s a well-known activist, Marshall Ganz. He’s at the John Kennedy School today. He’s teaching activism, if that helps. Of course, I had a mad crush on my English teacher who was gay, but I didn’t find that out until later. Let’s see, free speech, Vietnam protests. I taught at Upward Bound at UW. I was in the Big Sister program.

Prahl: Tell me about both of those programs.

BAROSS: The Upward Bound program, they take the poor people who are promising—kids who are promising and give them special classes in the summertime, and I taught filmmaking. That was the first time I heard how bad it was for the Black people, because this girl told me that her whole family had fallen apart because her mother got in a car wreck. She’d gone in and this White doctor wouldn’t touch her. He was from the South or something. So she died of internal hemorrhaging. The father started drinking, the kids running wild. I think her brother got shot or something. What? This was all new to me. So all these kids have these horrible stories.

Prahl: Was that your first attempt to teach?

BAROSS: I guess it was. Later I taught at Oregon State. I taught filmmaking there.

Prahl: When was that?

BAROSS: Between ’71 and ’80 something. That was filmmaking.

Prahl: Were you still living in Corvallis then?

BAROSS: Yes. I remember teaching there. The Big Sister program, I decided, well, I don’t have kids but I want kids, so I’m going to get me one. So I went to the Big Sister program and they gave me this lovely little 11-year-old girl. So today now she’s almost 40, she has three children.

Prahl: You’ve stayed in contact with her?

BAROSS: I’m Grandma Jan, yes. Isn’t that cool? She married a Menashe, but she’s not Jewish.

Prahl: What did the program expect from you? What did you do?

BAROSS: Oh, you just stay in touch. You make your own arrangements. I said, “What do you want to do?” “I want to go ice skating.” “Okay, let’s go ice skating.” “How about riding a horse.” She hated that. I saw her through so many horrible boyfriends but she got a good husband, and now her kids, three kids, from nine and then the twins are seven.

Prahl: Where do they live?

BAROSS: On Lombard, off Lombard. I didn’t have much to say over witnessing [a gap in the tape?] I think that’s about it. I’ll probably remember stuff later. These are my painting things and solo shows.

Prahl: Can I keep a copy of that for the files?

BAROSS: Sure. Oh, I worked on some feature films.

Prahl: Doing what for them?

BAROSS: Like second unit here, and line producer and production manager. Then I did some photography. I don’t remember any of this!

Prahl: The advantage of writing it down.

BAROSS: Documentary films. These are my documentary films here. Some film grants. And publications.

Prahl: That’s all the kind of thing that we’ve love to have in writing.

BAROSS: I should have brought you my publications.

Prahl: It’s not too late. And it’s also not too late if you think of other things, other stories. When this interview is transcribed I’ll send it to you and if one thing you read sparks another thought, we can add it in square brackets to say that you thought of it. And if you want to record more, we can do that, too.

BAROSS: I can’t think of anything else. I feel like I’ve been talking about myself.

Prahl: That’s what you came to do. I think you’ve added quite a lot. Thank you.

Wendel: . . .simple ones. I note your father passed at 54. What from?

BAROSS: A heart attack. It was a congenital thing. His father died really young. His brother had a million heart attacks, and then he finally died, too.

Wendel: Your father was the surgeon?

BAROSS: Yes, orthopedic surgeon. He was healthy until the day he died. His hair was black.

Prahl: How about your brother? Did he die of a heart attack, too?

BAROSS: No, he was in a very strange—we still don’t quite know. He lived in Mill Valley. He had this really nice big house. It was the night of one of the worst rainstorms they’ve ever had. In Mill Valley if you go back in there, the roads are like this, you know? He was on his way from the grocery store really late at night to his house. It was cold and it was raining. For some reason the car went off the road. He’d been there a million times, so I don’t know why. It went off the road and it got stuck way down there in the valley, not that far. Then we don’t know what happened, but he got out. I guess he couldn’t get back up because the mud was sliding or something. So he started walking and then they found him. He had to have stepped over, thinking he was stepping over something, but he fell about 10 or 20 feet, I don’t know, down to this cement, the back of somebody’s garage. It was cement there. You know where the gutter is? It was kind of—then he cracked ribs and stuff so he couldn’t I guess move, but he had also gotten hypothermia because they found him. When you have hypothermia you take off your clothes, so they found him with his clothes practically all off. Then you curl up in a ball like that when you have hypothermia, trying to stay warm. Your body thinks you’re too hot because it’s trying to keep your organs warm. Maybe you know all this. I just found out about it. So that’s where they found him, in this person’s back yard.

Wendel: How horrible. How old was he?

BAROSS: 68. He could have been saved a few hours earlier if they’d found him.

Prahl: If anybody had seen the car go off the road.

BAROSS: What happened, this woman was walking her dog and saw Tom’s car down there. She reported that and then they searched for about four hours before they even found him, because they didn’t know where to look.

Wendel: How long was he missing for?

BAROSS: Well, I guess the whole night. It was about 12 o’clock when he went to buy something and then go home, so around 6 in the morning, maybe. But it was cold and it was raining. It was a crappy way to die.

Wendel: I noticed you had a long list of documentaries. Obviously when you make a documentary you must be very passionate about the topics. Can you talk a little bit about some of those topics?

BAROSS: The one I’m doing about my mother is one I’m passionate about because her life is so interesting. I’m just going to look at the names.

Wendel: That first one, Happy Steps?

BAROSS: I’m all done with that. The first two I’ve done. I can give you copies of that if you want. She’s Jewish, you know. This one is 3 O’Clock High. I just did a little work—it’s called second unit, where they needed this—well, I’m not passionate about that. There was this huge bug coming, so I had to figure out how to make this bug come here. This was for the Steven Spielberg productions. They just needed a little—I’d don’t even know how I even got into that. Let me think. Peter Watkins, The Peace Feature. Do you know Peter Watkins? He’s a peace activist and he makes films. I worked on it with him. Then Shadow Play was the first feature film, and Unhinged. Both of those were feature films that friends of mine made and I worked on to help out with them. Those are feature films. Then I wrote a feature screenplay, The Last Seduction of Mata Hari. That got a Willamette Writers award. Who knew? Then Women in the Director’s Chair. Oh, God, I didn’t put what the film was. Well, there, my mother won an award, Women in the Director’s Chair. That was the film festival, that one of these films I was telling you about got an award. These are just the film festivals where I won some award, so I don’t remember what the films were. Oh, here we are. That Five Star Feeling that won. Everyone Hates My Dog, about my dog. That was very funny, everyone just—Oregon Jews, and you’ve got that one now. Footsteps of Columbus was for the Neveh Shalom synagogue. Do you have that one? Pioneer Women, Clackamas County Historical Society. I don’t know if you’re interested in that one. A woman (she’s not Jewish) but she wrote this long poem about pioneer women coming over on the Trail to here. So we took her words and made—we got a covered wagon, we got everybody dressed like pioneers, and we kind of acted out taking pictures as though it were an old photograph album. That was really fun, and we had to raise money. The reason I kind of gave up all this stuff is that in those days you had to raise so much money to make a film that it was years.

Prahl: Is this still true today?

BAROSS: Well, now you can do it with your phone, you can make a movie with your phone. I can’t remember the one they did about that musician. There was one about a famous one.

Wendel: The Detroit musician? Where he was a pauper and he didn’t know he was rich and then in South Africa he was like an Elvis Presley. We saw that together, with you and your husband.

BAROSS: What was the name of that, do you remember?

Wendel: It’s on the tip of my tongue. Rodriguez.

BAROSS: Rodriguez. They did that with a phone, I was told. Is that cool?

Wendel: That’s really cool.

BAROSS: That was great. Then Rocky Road. I don’t have to go through all this.

Prahl: I’m turning this off. Thank you, Jan.