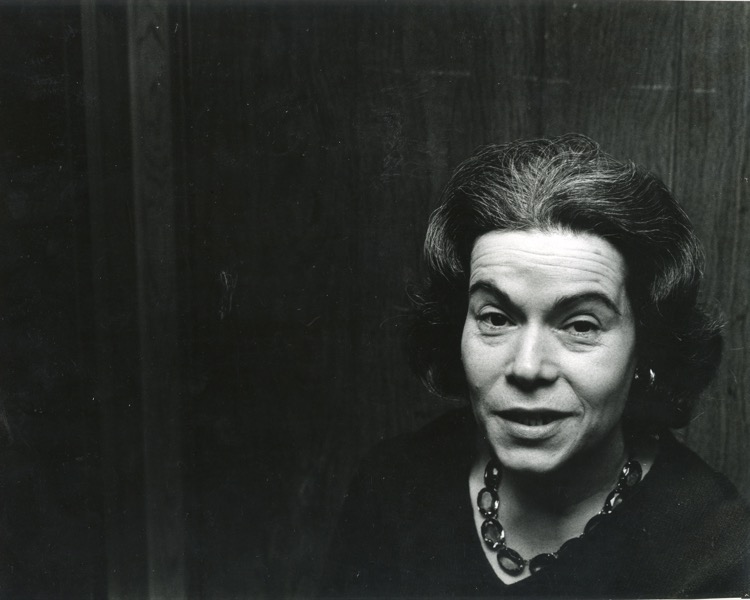

Diana Galante Golden

1922-2013

Diana’s large Sephardic family included her father, a merchant who owned a dry goods store, her mother, two sisters, one brother, her grandmother, and an aunt, who was blind. They were part of a Sephardic Jewish community of about 10,000 living in one section of Rhodes. Diana’s older sister and brother lived in Morocco.

In June 1944, the Germans entered Rhodes and in July the Jews were rounded up and deported. Diana’s family was shipped first to a detention camp near Piraeus and then on trucks and in box cars to Auschwitz, where they arrived on August 16, 1944. Diana’s father died in the transport through Yugoslavia. In Auschwitz, Diana’s aunt, mother, and younger brother were separated from her and subsequently murdered. She and her two sisters clung together as they were washed, shaved, starved, and marched to a barracks at Birkenau. They worked there until the Germans evacuated the camp, and they were sent to another camp in southern Germany where they worked in a machine gun factory.

On May 9, 1945, the Russians liberated the camp, and Diana and her two sisters were transported to Austria and eventually to Italy in September 1945. With help from the Red Cross and the American Jewish Committee, they regained their health and joined their older sister and brother in Tangiers. From there, they began their emigration to the United States, starting with Diana’s two younger sisters. Diana’s emigration was sponsored by family members in Los Angeles, and she arrived in New York on February 10, 1948.

After moving to Seattle, where she worked as a sales girl at I. Magnin, Diana met and married her husband, Kenneth Golden in 1952. They settled in Portland and had two daughters: Estelle (born 1955) and Elaine (born 1958). The family joined Congregation Neveh Shalom, and Diana also joined the sisterhood of the Sephardic Synagogue, Ahavath Achim.

Interview(S):

Diana Galante Golden - 1975

Interviewer: Leslie Semler

Date: September 21, 1975

Transcribed By: Unknown

Semler: Where were you born and raised?

GOLDEN: I was born on the Island of Rhodes, which at that time belonged to Italy, and I was also raised there.

Semler: Were there many Jews in that community?

GOLDEN: Yes, there were; there was quite a large Jewish community there. I would say approximately, at the peak, there were about 10,000.

Semler: What was the population of the island?

GOLDEN: About 60,0000. There were Greeks, Turks, Roman Catholics, and Jews.

Semler: What was the Jewish community like then?

GOLDEN: It was like a self-imposed ghetto. In other words, the Jews lived in one separate section, the Greeks in another section. It was like a big family, many interrelated. The synagogue was within walking distance, the school was within walking distance, and we all went. All the Jewish children went to the Jewish Parochial School. All the studies were done in Italian; however, we did have Hebrew and Bible studies every single day.

Semler: Was there any hostility between the different communities?

GOLDEN: No, more or less we had a peaceful co-existence. We were in touch with each other.

Semler: What kind of political leaders were you under?

GOLDEN: Fascism. It was the Mussolini regime. We had the government of the island. It was under Italian rule, and at that time fascism went all the way up before it tumbled down [laughs], but we were not persecuted. We were not mistreated. However, in 1936 or 1937 when all this trouble began, I would say when Mussolini allied himself with Hitler, then the antisemitism began, and the press, little by little, took various steps against the Jews. It was mostly the press at the beginning.

Semler: How old were you then?

GOLDEN: Well, I was born in 1922, so I was already about 14 or 15 years old when this antisemitism business began. Right at that time the Italians occupied Ethiopia, Eastern Africa, and that is when things started to go bad for us. There were many Jewish young men who enlisted in the Italian army, and right after that, little by little, they started to be isolated.

Semler: As a little girl, did you have any hostile feelings towards Hitler and Mussolini?

GOLDEN: No, not at all. We were well treated. It started to go bad for us only in 1936 or 1937 when Italy was boycotted as a result of the occupation of Ethiopia. That is when they sanctioned Italy. Great Britain and America sanctioned Italy because they occupied Ethiopia. Mussolini found Hitler, or Hitler found Mussolini as an ally, so he started to follow the same path as Hitler, and the very first thing was to immediately take it out against the Jews. However, most of it was press, really. We were not mistreated, we were not in any way except by the press, and also, some people who occupied positions in the federal government, like the post office, they were dismissed.

Semler: What do you mean by the press?

GOLDEN: The newspapers. The radio. They wrote some things not kind towards the Jews. They would say that we exploited other people, that the world was in trouble because the Jews were dominating the banking situation throughout the world. In other words, we were pictured as vultures living on other people’s blood, let’s put it this way.

Semler: Was this around the time you were deported?

GOLDEN: No. Oh, no. We were there when the war began. We were deported in 1944 because the Germans first came as allies onto the island to work with the Italians, the troops, but then they fought against each other. In 1943 Mussolini was ousted; in fact, he was killed at the time, and an Italian general took over. Then most of the Italian troops sided with the general, and they did not want to be on the side of the Germans. So they also had it very bad; many, many of them were killed. Right after that they got rid of the Italian soldiers who didn’t want to work with the Germans, or to follow to Germany and to combat on the side of the Germans. After they were eliminated, then our turn came. We were deported in July of 1944.

Semler: Do you remember anything about the deportation?

GOLDEN: Very much. It is all very clear in my mind. Until the day I die, I will never forget it. It was a horror. First they asked all the men to present themselves to a certain building, let’s say like the police station, all the men from 14 years and up, with the pretext that they would go and work in the field to build trenches close to the beach. They were asked to come and work in the fields. Right after the Germans occupied the island, which was in about June of 1943 [transcriber note: she must mean ’44], they issued identification cards to every citizen there. We all had our pictures on the card, and of course we were labeled as Jews.

Semler: And this was only throughout the Jewish community that they did this?

GOLDEN: To everyone, because there was a curfew. Everyone on the island had to have an identification card. In the first place we had food rations and we had to have cards, but when the Germans took over we also had to have our pictures on there so they knew exactly. They had the books stating who was Jewish, who was Turk, who was Greek, and the residency. In other words, they could round up everybody in a matter of hours. The island was small; we were all concentrated in one spot anyway. So they asked all the men to come, and they knew how many were of that age, and they also stated that for every man who was missing they would kill five of the ones there. Of course, we were very scared, to say the least. We were terrified because we knew they meant it. They killed indiscriminately. We knew that. So my father and all the men who were anywhere between 14 and 65, they all went there. They kept them there overnight, and the next morning another bulletin came out saying that all the women and children should go and join them, and for every family or every person who was missing, they would kill ten men at random. Most women had either a son or husband, or both, and nephews. All our families were there. Of course, we wouldn’t want to jeopardize anybody’s life — be it family, or friends, or neighbors — so we all went there, and they did ask us to bring some food for a couple of days, whatever we had with us, and clothing. All we could carry on our backs. No luggage. We had to carry everything in knapsacks on the back. That’s all we could carry, nothing else.

Semler: Were you afraid at this time? Were you aware of what was going to happen?

GOLDEN: We knew the end was coming for us. Although we did not have radios, we did not have newspapers — there were newspapers, but they printed only what they wanted to print — we were aware, I don’t know how, but we were aware that there were concentration camps, and they were deporting people from Germany to Poland. There were concentrations camps in Germany, all over Europe. We knew the plans of Hitler, not in detail, but we knew that they were persecuting the Jews, that they were taking all their possessions, all the property, whatever they had, and they were putting them in concentration camps. But we really didn’t know to what extent these concentration camps were, what was going on there really. I don’t think that any human being can imagine that things like that could exist in this century, and done by people who supposedly were educated and were very high in science. We could not imagine that they could have such bestialities, such heartlessness.

Semler: It is often wondered why the Jews, when the Nazis came and knocked on their doors to round them up, why they didn’t just shoot them then and end it all before it even started.

GOLDEN: I can’t say of other people, but we on the Island of Rhodes did not even possess a gun. The only thing we had was a knife, a table knife to cut bread. That’s the extent of it. We did not have radios, we were not allowed. When the Germans took over, all the radios were confiscated. We were afraid of spies. In other words, we knew that they would resort to any means to spy on us. Food was very scarce, so they would give food to some people, and when you are hungry then the situation changes. A person is capable of doing anything, of betraying his own father. When you are hungry or thirsty, you don’t have anything to eat, you just say, “Well, I have to save my own skin.” So we could not fight them. They were all armed. They were all with sub-machines [guns] and we were really very tired through[out] the war. We had many bombings, many homes were destroyed, many people had died already, and we were all in hunger. We didn’t have much food left because there was a block[ade]. In other words, what was raised on the island was not enough for everybody. And we, the Jews, did not possess any land to plant anything. The commerce was in our hands. Banks belonged to Jews. Most of the stores — clothing, or shoes, or necessities for the home — were owned by Jews, but when it came to building, for instance, there was not a Jewish man who was in the building trade. Nor in the farming trade at all, not a one. So we didn’t have any food. The only thing we had was gold — from chains, or watches, or bracelets — or oriental carpets, for instance. So we used to trade. The older farmers were either Greeks or Turks. They didn’t want any money because the money was worthless. It was just a piece of worthless paper. So we used to give them a gold chain or some nice crystal, or some nice silver spoons, or flatware, or vases. Whatever we had that had intrinsic value, we used to exchange.

Semler: Was there any food imported or exported?

GOLDEN: Very few boats went through. All the island was mined, and the Jewish quarter was close to the port, so many homes were destroyed because the bombs missed. We were bombed by either the British air force, or by Americans, mostly by the British because the planes came from the islands of Malta and Cyprus, which are close to Rhodes. So within 20 minutes of flight, they would come and bomb the island because they wanted the surrender of the Germans. But that never came, not even after we left. They kept bombing and bombing, and then at the end of the war, they just came and it was over.

Semler: Was the Isle of Rhodes considered on the German side of the war?

GOLDEN: No. However, I must say that the Greeks were rather friendly with the Germans because they felt that if you are against the Jews, then you are with the others. So they befriended, some of them. Others were just completely impartial. Everyone was terrorized. In order to save their own skin, they never showed any emotion or complained or asked, “Why are you doing this to the Jewish population?” Nobody lifted a finger to save us. They couldn’t, really. It would have meant jeopardizing their lives, and if you think that other persons would jeopardize their lives for the Jews, that was not the case. Even if some, I’m sure, felt sorry for us, they couldn’t do anything.

Semler: Are you bitter towards anyone for not doing anything to help?

GOLDEN: No, I’m not, because I don’t think it would be possible unless you really were an idealist and said, “I’m going to risk my life and save a Jew.” There was no love between us anyway. Rather, I must admit that there was plenty of envy. They felt that if the Jews were out of the island, then they would get all the things from the Jews, which they did. After we left, many people heard that we were all exterminated, so they went and lived in our homes.

Semler: What happened after you were all rounded up?

GOLDEN: We all went to the police station, and we were kept there for three days. Then they asked us to go to the port. They sounded the siren — it was like an ambulance, like when they had the raids — and everybody went. There was not a soul in the streets. We marched from the police station to the port. They put us in two boats. We were 2,500 persons at the time — that’s all that were left in Rhodes — with the exception of about eight or ten persons left there because they still had Turkish citizenship, so they were protected by the Turkish counsel. The rest of us were all Italians, and we had no rights since the island was already in the hands of the Nazis, of the Germans. They took our papers, identification cards, one by one. They inspected everybody, and there was no one missing.

Semler: What was the name of the camp that you were sent to?

GOLDEN: First of all, it was Auschwitz, in the Upper Silesia.

Semler: Did you go straight to Auschwitz?

GOLDEN: No, it took a full month until we reached Auschwitz. We stayed about eight or nine days on the boat, and we reached Piraeus, which is the main port near Athens in Greece. We disembarked from there and walked for about three miles. They took us to a detention camp, and we stayed there for two days. Then we were brought back again, not to the port but to a railroad. We were put in cattle wagons, boxcars, and it was written there in French and in Italian that it could carry 40 horses, and we were in our boxcar 77. There were others with 100 persons inside. There was just a little window in that boxcar, and it was right in the heat of summer. So we were rounded up, and we had to walk very fast. They were hitting right and left indiscriminately and saying, “Quick! Quick!” and it was very, very hot at that time. It took us about 15 days, I believe, to arrive in Auschwitz. We went through Greece, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and we arrived at Auschwitz finally on August 16th.

Semler: And you had very cruel treatment during the whole trip?

GOLDEN: It was a horror. Many died. My father died. He was not together with me; he was in the next car. My grandmother died. We were all full of lice. We did not have water. During the day, the train would stop a couple of times. We were all sent out with big sticks, “Hurry, hurry, hurry,” and we had to do the personal means in the middle of the fields. Men, women, and children, like animals. Many people were sick. Many had dysentery because the water that they gave us came from a barrel. There was a barrel of water in each boxcar, and the barrel contained olives before. They were not washed properly, so the water was rancid. It tasted terrible and it smelled terrible, but that was the only water we had to drink. One man in each boxcar took care of distributing the water. As smelly and horrible as it was, we were very thirsty. We did not get any food. We had some food with us, a piece of bread, a piece of … but by the fifth day many people were dying already because they just didn’t have anything. As a matter of fact, before we went in the boxcar, they gave each of us a little piece of bread about the size of a hamburger bun, and that was all the food. Then, about four or five days later, they gave us again another little bun, and some raisins, and that was all. And we had a cup of water during the day; that was all we could have, that rancid water.

Semler: What did they do with the bodies that they took off the car?

GOLDEN: Took them out. At every stop, wherever we stopped, they went around saying, “Is there anyone dead?” They used to say, “Kaput, kaput. Bring them out.” So they put my father in his own coat, and four persons carried the body out. They gave them shovels, and all they could do was to just dig a shallow grave and leave him there. He died and he was buried in Yugoslavia. My grandmother died a few hours after we went in the … and she was buried someplace in Greece and my father in Yugoslavia. Those were the only two members of my family who died during the trip. My mother was very sick, but still living when we arrived in Auschwitz. Many died. I don’t know how many.

Semler: Were you terrorized to see people dying all around you?

GOLDEN: Yes, we were terrorized. We were all crying. We were praying that if the intention was to kill us, that please the end should be coming very quickly, that they would do us a favor to just round us all up and put dynamite in the boxcar, or just put all of us in the fields and shoot us like you shoot birds.

Semler: Did you have very religious feelings at the time?

GOLDEN: We prayed. Oh, definitely. We were praying. In each boxcar, someone took the lead. During the day, in the morning, he would say, “Let’s all say the prayers.” When the boxcar used to open, we knew that they were coming with the whips, so the man used to say, “Let us all say the Sh’ma; let us all pray together.” We really were expecting in one of those stops, since we were all in the fields and there was no one left inside the boxcar, that we would probably all be rounded [up], and the guards would just shoot us all and get rid of us once and for all. We really were expecting that, and we were hoping also that that would happen because it was so horribly hot, and we were full of lice, our bodies, our hair. Everything was just sickening. Many people were sick with diarrhea and doing their personal functions of the body right there sitting in all that stench. By that time we knew we would never come out of it alive, so we were hoping that they would just get rid of us and that would be the end of it.

Semler: What kind of feelings did you have towards death then?

GOLDEN: At that time, we thought that death was the sweetest thing that would happen to us, because of the suffering, to know all of a sudden that we were dehumanized. We lost all kind of self-respect. No one did anything wrong to his fellow man, I don’t mean that, but we all had our own privacy in our own homes, in our own rooms, and all of a sudden you are doing your very private needs in front of other people, and you feel naked altogether. You’re also demoralized because you are treated worse than an animal. You cannot contemplate that kind of treatment. And we knew their intention was to kill us. Well [we thought], they may as well kill us in one shot. Then it will be over quickly rather than this continued suffering hour after hour, not knowing how long we will be suffering like this.

Semler: Have your feelings towards death changed now? Are you afraid of death?

GOLDEN: No, I’m not afraid of death. I’m more afraid of suffering; that I’m afraid of. I pray still that when my time comes, whenever it is, whether it’s in three minutes or three years or in three days, I pray to God that it may be quick.

Semler: When you got to the camp, were you separated from your family?

GOLDEN: Yes, that was the separation point. My mother’s sister was blind. I was holding her by her hand. My mother was with my little brother. At that time, he was 11 years of age. My other two sisters, we kind of stuck together. We held hand by hand. There were several officers of the SS inspecting everyone coming as we came out of the boxcar. They were looking at us and separating. He asked me to let my aunt go, and I did not do so because she was blind, she would not know what to do. So I signaled to him that she could not see, and he came with the back of his hand, he slapped my face and threw me to the ground, and he grabbed another woman who was standing there and asked her to take the hand of this blind woman, and he pushed them all away. And that was the last time I saw my mother, my brother.

[Tape 1_1 ends here, and tape 1_2 continues.]

It was the very last time that I saw this part of my family. They were looking at us, and the ones who were separated on one side were all young men and women who could work, do something. They had no use for young children, for the elderly men and women who were there looking at us. They felt that they were useless people — because we were in such a state — that they couldn’t produce anything. So we never saw them again, and the fate of those who were not in the working camp, in the labor camp where we were sent, then they were all sent to different barracks and exterminated. They would send them to the showers telling them that they were going to take a shower, and they gave them a piece of what you called soap. And instead of water coming from the shower, some kind of poison gas came, and they all were dead or nearly dead. And the floor opened, and they were all thrown down in another chamber where all the gold of their mouth was extracted, if they had any gold teeth, by a crew of prisoners. And then they put them in ovens, and they also made soap from the ashes. All they could take out of the cadavers, they extracted everything they could. Whereas we were sent already to a camp. We walked two or three miles and it was nighttime. We didn’t know where we were. We knew we had already entered the camp because I remember the heading in German, which meant “Work makes you worthy of living,” that’s the translation. “Arbeit macht …” something. In other words, “Work makes you worth your living.” That’s it.

Semler: Were you aware of what was going to happen to your mother or brother?

GOLDEN: No, we did not know. We didn’t know that such a thing existed. Really. We just had no idea. We thought in the beginning that we would be put in some kind of camp or in a compound where we would be taking care of ourselves. We probably would be left alone, the only thing just being separated from everyone and everybody, maybe in huts, maybe in barracks. But we really didn’t think that we would be taken off of the island because honestly, they did not have any means. They were very short already in boats, so we didn’t think they would bother with us. We were like a bunch of sheep; we were people who never held arms, who never sided one way or another. We did not demonstrate. We were just a bunch of scared people, and all we wanted was to be as small as we could in order to be left alone. We really couldn’t do any harm to them; we didn’t do any harm to anyone.

Semler: How many people were in that labor camp?

GOLDEN: Oh, that I can not say. There were barracks, barracks, barracks, as far as the eye could see. And all the barracks were separated one side to another with electric wires. There were no walls to separate one row of barracks from another row. All there was, was barbed wire, but it was all electrified, so that if someone chose to hang on to the wires, I would say that in a minute or two that person was electrocuted. Every day there were several who committed suicide that way. So we couldn’t go any place, we couldn’t escape. That was impossible.

Semler: Could you give me a description of the camp or your living quarters?

GOLDEN: It was all dirt. There was no cement, no grass, the floors were all dirt. There were wooden barracks, and there were three cots, in other words, three layers. It was all planks, no mattress, no pillow, nothing. I would say that the cots were about the size of a double bed, and we had to sleep ten there. Ten girls lined up like sardines. We couldn’t lay flat, we couldn’t lay any other way, just on the side on the planks. We were told to take our shoes and put them under our heads because if we left them by the bed, we would not find our shoes in the morning. We didn’t have anything left by then. We were completely stripped of everything. The only thing that we could hold in our hands were our shoes. All clothing was taken from us completely. That was in one room. Then we were processed into another room, and all our hair was completely shaven from every part of our body. In a way that was good because we were full of lice, and that was one way to get rid of it. So we were shaved, and in another room they gave us a piece of soap, which was sand and put together with something, and we were told that we were going to take a shower. The water was very cold, and within two minutes, by the time we put the soap on and scraped our bodies, the water was off and that was that. And if we would say something, some other women came who were the leaders, the kapos we used to call them, with whips and start to whip us out of the showers. They threw at each one of us as we got out of the showers — no towels to wipe off, nothing — a piece of clothes, a dress or a nightgown, what ever came to their hands. They had piles of clothes from other inmates, and that was the only piece of clothing we had on, no underwear, nothing.

Semler: Did you work there? What kind of work did you do?

GOLDEN: Well, for a week we did not work. They took us to the barracks, and they said this is your place. There were thousands of inmates already there, thousands, but the barracks were occupied by Polish women, all Jewish, of course. By this time they were like animals. They had been in camps since 1940, so by this time those who survived were so hardened that they looked at us with hostility. We could not communicate with them because we did not speak Yiddish, and they could not comprehend why we Jewish persons could not speak Yiddish. They wanted to be reassured that we were Jewish. We told them in Hebrew, and quite a few of them could speak Hebrew. So we spoke whatever we knew in Hebrew, conversation or words, or we recited the Sh’ma. We told them about Pesach or Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur, words that only a Jewish person would be acquainted with. They still were very surprised because we didn’t speak Yiddish, so we told them that we were Italians, and they called us Italianos, that’s all at that time, and we just couldn’t communicate with them. Then other women came the second day, some French women came — some from Belgium, some from France — and they came to see us. They already knew what was happening, where we were, what was the procedure there, and they told us to forget about the others. We were thinking that we would be reunited with our parents. They said, “If they are not in this camp with you, don’t hope to see them. That’s all.” They pointed at the high chimneys with flames coming out, and they said, “They are being gassed and cremated.” They said it very clearly, and they said, “It’s a horrible thing to tell you that, but that is the fate of all those who don’t come to this side.” Many could not accept that, and so immediately within a week about 60 or 70 of our girls were dead already.

Semler: They committed suicide?

GOLDEN: No, from shock. Just the shock of being … just completely, they fell apart. We were all weak to begin with from the months in that horrible train. We were weak, but especially those who did not have sisters, who did not have cousins, who were alone. When I think about it, I wonder, “How did I survive? What made me stronger than others?” And I really find myself answering to myself that it was feeling for my sisters. I had to live for them, they had to live for me, so we lived for each other. We knew that if I gave up that they too would give up, and they thought the same. I mean each of us, individually, we gave each other the strength to do our very best, in other words, not to give up. To try to live, to survive. Many tried, and they just couldn’t. There was typhus. There was trench mouth. They could not open their mouths. They were full of canker sores, so they just couldn’t eat anything. They couldn’t open their mouths to eat, so dead bodies were there like flies. In one row of barracks — every barracks had about 300 … and every morning at 4:00am — it was still very dark — they used to call us to get up, and we formed lines of four in a row, all lined up. and we were not allowed to touch one another because it was very cold, even though it was in August. The nights were very cold. The days were very hot. We were not allowed to be one against another. All we had on was just one little dress, nothing on, and no shoes. By this time many of the shoes had sank in the mud, and some of us didn’t even have shoes anymore. Those who didn’t have shoes were able to get wooden Dutch shoes — clogs — and they were very big clogs. Some women had very small feet, and they couldn’t even walk with those clogs on.

Semler: Where did they get those shoes from?

GOLDEN: I don’t know. They probably took them from Holland, I suppose. I don’t know. Every clog was about ten pounds each; it was the traditional type of clog. So we were there for about an hour standing in that cold, freezing, and that kapo, or the leader there, had her own nice little warm bed with cotton sheets all over. They were all dressed nicely with leather boots. They were Jewish women, but those were the ones who really were put to the test. They survived. They looked healthy because they ate well. They had hair, long hair or medium hair. They had a little room at the entrance to the barracks. It was heated. They lived very well. They had their own food. They looked human. We no longer looked human. We looked like walking death, like skeletons already, but in spite of that, we made it through.

Semler: How did those women get in that position?

GOLDEN: Well, I honestly don’t know. We didn’t dare talk to them. We couldn’t speak with them anyway; we didn’t know Yiddish. But we heard from either French or Italian girls who were there. They said that these women were the women of the guards of the camp, in other words, they were their mistresses. They could be trusted by the SS to be mean enough, not to make our lives … even with words.

Semler: But they were Jewish?

GOLDEN: Oh, definitely they were. Certainly. But they had been inmates for a long time. Some of them, at one time or another, had children by the SS. They had been made prostitutes, whether they wanted to or not. So by this time they didn’t really care much about us. They said, “Well, I’m just trying to save myself. You do whatever you want.”

Semler: Did you make any close friendships?

GOLDEN: Yes, by close I mean that some of the girls who spoke French or Italian, or the Greek ones, they came and talked to us. They kind of gave us comfort; they couldn’t give us anything else. They gave us the guidelines on how to survive. Now that you are here, it’s up to you. If you just want to hang yourself on the wires, you go ahead and do it; that will be quick. But if you want to survive, you just have to be very, very strong to survive this. In other words, don’t let this just completely demoralize you. That’s what they want. They want to kill us by slow death. Now we just have to sweat it out. In other words, be your brother’s keeper. You give your brother or your sister — we were all women anyway — your courage, and she will return the courage. Find someone, even if you don’t have anyone who’s in your family here, find someone who’s in your group, and pledge life for each other. And somehow, after the initial agony, some were determined to follow this, to find someone who we could dedicate our life to, and they would dedicate their life to us so that we would do our utmost not to die by our own hands, and that gave courage. In spite of all that, after a few days, they said, “Now, you have to sing.” We were allowed to sing during the day. We could not return to the barracks at all until nighttime, and the days were very hot. After we were lined up there in the morning, they gave us a bowl of what they called coffee, but I think that all it was … maybe it was boiled grain. It was something like colored water. That was all we had in the morning. Then for lunch they gave us a bowl of soup. We did not have any dishes. We didn’t have spoons, no forks, nothing. Everything was liquid anyway. They used to have at the entrance to the barracks so many containers, either rusty cans or whatever there was there. So we used to pile up to grab one because there usually were less containers than human beings. From mouth to mouth. They were not cleaned up. That’s how the disease was rampant. For lunch they gave us another little bowl of soup. We could not keep anything, even if we wanted to; there was no place to hide anything. We were wondering why they took our combs, or brushes, and they said, “You don’t have hair. What do you need them for?” Only in the morning was there water, and there were big signs, “Water is not to be drank. You’ll get sick if you drink.” The water was brownish because it all went through pipes which were rusted. There was no water to drink, period.

Semler: What did you do all day? What kind of work did you do in the camp?

GOLDEN: For one week we didn’t do anything. We just sat on the dirt, that’s all. Then in the second week, strange enough, we were in line, and they took us to another camp. We picked up bricks. Now you know that bricks have the facility to retain heat as well as cold. These bricks were out over night, and they were very cold. Each of us had to pick up three bricks, and we had to keep them close to our stomachs, hold them against our stomachs. We were not allowed to walk holding them far from our stomachs. Like when you put a heating pad, but this was a cooling pad, and we had to walk. These leaders — in front and in the back there were two German women; they had the SS uniform — and each had a German Shepherd. We were told that all she had to do was to snap a finger and the German Shepherds would tear us all apart, so don’t try anything against the orders. We had to walk for about two miles with those bricks, cold, cold, right against our stomachs. We arrived at the other side of camp, we left them there, and we walked back to our own camp. Then the next morning we went back there, and all we did for about one week or two was take bricks from one place, put them in another, back and forth like that. Stupidity, but that was the punishment. Then later on they made us pick up pieces of grass, squares of grass which grew in one part of the camp. It was cut by other inmates. All we had to do was lift it from the ground and take it back to another camp because they picked up grass with the ground, you know, to plant it in another camp. I would say it was about two or three miles of walking back and forth, and really we were so weak, we didn’t have strength to walk, but they told us we may sing. Now that was one thing that was never forbidden. They’d say, “Sing,” and somehow they’d like to sing Italian songs, I mean they’d like to hear them, so they used to call us and tell us, “Italiono, you sing Italian songs.” So we used to sing, whether we felt like singing or not. At least we were kind of cheering up ourselves. It went on until the end of October like that. In the meantime, many died. By that time we’d already started to hear airplanes going by. We heard artillery or whatever, cannons sounding from a distance and planes flying overhead.

Semler: What kind of planes were these?

GOLDEN: We were not allowed [to look]. When we heard the siren, we were asked to go in the barracks. We could not ask any questions. We knew they were probably Russian planes. We also knew that there were camps nearby which were occupied by citizens from Poland, and Russians. A few times we saw from a distance, many women in uniforms, walking. The women had hair. They had those striped uniforms with white. They had shoes. They looked human, at least from a distance. They were clothed. They were not like us. Some of the other women who were inmates long before we were told us that these people were political prisoners. So they were looking at the camps. The Russians … we were quite sure they were Russians; we really didn’t know what kind of planes they were, but we assumed they were Russians because they were closer than the British or the Americans. So they were sizing up the camps and probably taking a look at the activity in the camps. By that time already, by the end of September, they started to deport people out of the camp into other camps. I assume that they were planning to evacuate as the Russian troops were approaching because after the war was over, we heard that by the beginning of January there was no one left in that camp, just those who were near death. They couldn’t walk, they couldn’t do anything, so they left them to die without food, without anything, and many died.

Semler: Could you tell me a little about your feelings at the time of the liberation of the camp?

GOLDEN: We were very happy, although after having suffered so much, really … at the very end, incidentally — I’ll make it very brief — we were lucky in one way because we were not asked to march into another camp. There were many who were forced to march for miles and miles. Many, many died. Others were shot. Others were left in the snow. By that time it had started to snow, and they were left in the snow all frozen. Thousands died this way. We were fortunate because we were put in boxcars and taken to Germany. There at least they gave us a pair of boots, wooden boots, wooden soles but leather tops. They gave us a pair of panties, which we could not believe, and a piece of clothing. We were in an extremely clean place. Each of us had a little tiny bunk all by ourselves. One in each bunk, with a straw mattress. Although the place was just all cement and the floors were wooden, it was all very clean. We were not allowed to have anything with us, nothing. We didn’t have anything, but the place was clean.

Semler: Who were you liberated by?

GOLDEN: By the Russians. But after staying there until March, we heard plenty of bombings in the vicinity. At that time in Germany we worked in a factory, in an ammunition factory. We were making holes in pieces, which were part of machine guns. We worked one week at night, one week during the day, and they gave us, I would say, two slices of bread per day and a bowl of soup, which was much better. It was clean. We were guarded, not by Jewish women; we were guarded by SS women. We kept working there until the very end, which was sometime in April. Then we were locked in the barracks, and they left us there for two days. We thought really that they were going to blow us up to pieces. Then for some reason or another they came back, they unlocked the doors, and they put us back in the train. They took us for about twelve days, here and there. I don’t know where we stopped, really. They stopped in several places, but nobody wanted us. Finally we ended up in Theresienstadt, which was in Czechoslovakia, and this Theresienstadt was a camp, but it was guarded by Jews. It was a fortress. There we were handed to Jewish guards, and that was the last time we saw the SS women. That was April the 25th or 26th. Then within a week, on May the 8th, we were liberated by Russians. Happy to be liberated, really.

Semler: How soon after that did you decide to emigrate to the United States?

GOLDEN: We were in camps until September, from place to place, because we were Italian citizens. Since the Italians were allies with the Germans, they lost the war. They didn’t have trains; they didn’t have any means for us to return to Italy. So everybody went home, and we did not. We were still sitting there in one camp or another. We arrived in September, and immediately we were put in touch with the Red Cross. They asked us to fill out all kinds of information regarding relatives in any part of the world — the Red Cross and the American Jewish Committee. Some women and men came, and they spoke. They had some special camps where we went. Or I would call them offices really; they were not camps. We went there, and they gave us temporary identification cards saying that we were …

[Tape 1_2 ends here; tape 1_3 begins.]

We were liberated by the Russians, and finally in September we arrived in Italy along with Italian prisoners of war who were in Germany, some by their own volition, others deported by the Germans. Anyway, we all arrived in Italy, and we went to the Jewish Community Center in Bologna. We stayed in Milan for a few days, but then we heard that there were other girls from Rhodes in Bologna, and we went to join them. We lived in what was left of the Jewish Community Center in Bologna, which is in the northern part of Italy. They were very kind to us. There was still a wing standing up; the other part was bombed down. They gave us a large room, about the size of this one, and they put little cots with mattresses and bedding, and a little kitchen where we all could cook. They gave us identification cards in order to go once a day to a public restaurant and eat. We were entitled to one meal a day in the restaurant. The other meal we had to prepare ourselves.

Semler: Did they give you money to go out and eat?

GOLDEN: Yes. They gave us enough. In the meantime, as soon as we arrived in Milan, the Red Cross and the American Joint Committee were able to get in touch with most of our relatives, and immediately we received from the United States packages. And also having relatives in here, they sent us a few dollars. They sent us clothing. Soap! Ivory soap was the very first one we received. I remember we also received cans of Heinz beans and cans of beef that you can slice, Spam. Cans of Spam. They were the very first ones to arrive, and Hershey chocolate bars. Ivory soap and clothing, although for some reason or another, the clothing, which was in excellent condition, was either too big or too small, but we interchanged. We started to gain weight rapidly but in a conspicuous way. From near starvation to overeating is a bad thing. Many of us really had a difficult time with diarrhea because we were eating too many sweets. We were eating too much, and our stomachs were not used to that. Several of us landed in the hospital, and were warned that we could die. Our stomachs would just stretch too much, and we would have bad indigestion and die. So we were really lectured, and we were all sent to the hospital individually. They gave us a little booklet to be examined from head to toe to see whether we had TB or any communicable diseases. In fact, some thought we were pregnant. We were never molested by anyone, really, but our stomachs, I would say actually that some of us looked four, five, six, seven, eight months pregnant. From the starvation and undernourishment, somehow the whole body is skinny but the stomach sticks out; it becomes bloated. I don’t know what makes it such. Our stomachs were just completely protruding. It was terrible, but we were told that gradually, if we didn’t overeat our bodies would return to normal function. For instance, all the time in the concentration camp, none of us had our menstrual period; it disappeared. Then gradually some returned sooner than others. Within seven or eight months after we were liberated, we began functioning normally. I myself, within a period of six months, gained a good 25 pounds. We were bloated really, our faces, our hands. We didn’t look normal. We looked rather inflated. But after the first yearning to eat, eat … we wanted to have a feeling of fullness with food all the time. So we kept eating continuously, whether we were hungry or not, and another thing, we wanted to take two or three baths a day, showers. Our elbows, our shoulders, some parts of the body, our feet, the ankles, the dirt was so embedded in our skin that we looked like coal miners. The dirt was there for months and months, not having the opportunity to wash ourselves decently with soap, with warm water. So we were all really, around our faces, around our nose … and in the meantime our hair was growing, fortunately, slowly because of the deficiency of vitamins. We were all given Vitamin C, Vitamin D, I don’t know, but we were all given vitamins. We were all also told not to overdo it. But anyway, little by little we returned to normal. They wanted to know where we had relatives, and if we didn’t have anyone, we could go to Israel. We decided … my brother and sister at that time were in Tangier, which is Morocco. They got in touch with us through the Red Cross, and they wanted us to go to Tangier. So we applied for a visa to go to Tangier, and we did go.

Semler: Were these the same brother and sister that were in the camp?

GOLDEN: No, the brother that I’m referring to now left Rhodes in 1938. He was one of the last ones to leave the island. My sister Rachel was in Morocco with my aunt since the age of ten. She departed in 1929 or 1930. She left our home. My aunt, my mother’s sister took her there, and she thought she wanted to educate her there, so she gave her a very good education. We got in touch with them, and we left, the three of us, for Tangier. From Tangier we corresponded with our relatives in the United States, in Los Angeles. They could bring one of us here. In the meantime, my younger sister met an American Jewish soldier in Bologna who came to the synagogue, and she already received a visa from her husband-to-be. While we were in Tangier she received the visa, and she was the very first one to come to the United States as a bride-to-be. Within three weeks of residence in New York, she married this young man to whom she’s still married. They sent the visa; my relatives sent the visa for me. I arrived in the United States in February of 1948.

Semler: Do you have any recollections of the immigration?

GOLDEN: Yes, it was very easy. I was fortunate that I was in Tangier because I was in the Italian quarter. The Italian quarter was one of the slowest to go because there were so many Italians who wanted to emigrate to the United States and not enough numbers in the quarter. But being in Tangier and having an Italian counsel there, it really made it quite easy. I only waited about nine months from the day I received the papers. Anyone who comes to the United States has to have a sponsor, or someone who will be responsible, so that the newcomer will not be in need of welfare assistance. Someone had to be responsible for me. They paid for my voyage, and I came to Los Angeles and lived with them for a year. Then I came to Seattle to visit other relatives. I liked Seattle very much. I liked the togetherness of the Jewish people there. At that time they all lived within a section. Most of them were Sephardic, and they spoke Spanish. Many of them knew my parents. I made quite a few friends there, elderly and younger people. So I was able to have more personal friends of my age there. I stayed in Seattle; I did not go back to Los Angeles. My relatives in Los Angeles were not offended by this. They felt I had a better chance of getting married there rather than in Los Angeles because being such a big city, it’s difficult to make acquaintances, to have friendships. All my relatives had either very young children … there was no one my age … but when I arrived here I was already 26, which in terms of American age — at that time, anyway — a woman of 26 is already past the prime of marriageable age. It becomes a little difficult when you say “26.” They would say, “Well, she’s already past.” But anyway, I stayed in Seattle with my relatives, and that’s where I met my husband.

Semler: How did you adapt to the new lifestyle? Did you find it difficult?

GOLDEN: No, it was not difficult. I came here with a heart full of love for my relatives, for this wonderful country. I did my very best to be on good terms with my relatives and with everyone with whom I came in contact. In other words, my attitude was one of cooperation, and all I wanted to do was to learn the language and just be absorbed into society as a normal human being.

Semler: Were your feelings towards the US different than they’d been before the war?

GOLDEN: Oh, yes! We all regarded the United States as the refuge of all the persecuted, where you had freedom of worship, where nobody would persecute you just because you happened to be a member of the Jewish faith.

Semler: Did you find that true?

GOLDEN: Yes, I did not become disenchanted in any way. People of my own faith were very kind, very good to me, my relatives especially. Within three weeks I started to work in a shirt factory. They were all very kind. At that time, they were all very much aware of survivors of concentration camps, and the minute they saw the number on my arm, I noted in their looks a kind of feeling sorry for me and trying to help in any way they could. In other words, you went through plenty, we will make it up to you. You will suffer no more. They were all very kind. My wish was to learn the language as fast as I could, and immediately I started to attend night school for newcomers. We started with the ABC’s [laughs] all [of us], a regular school. We were all foreigners from all over the world. My relatives were all very kind. I didn’t have to come home and cook any dinner or do any housework. All they wanted me to do was just to work, to be able to support myself, and go to school. That was all they wanted, really; they have not regretted it. I knew I was their responsibility, and I didn’t want to have any behavior problems in any way that they would regret. Every day was like opening a new page of a book. The words I was learning, and I was making very good progress, really. If someone spoke to me in Spanish … even if I knew I was speaking terribly or incorrectly, I used to just do my best to speak. I would ask everyone, anyone who came into contact with me, “Please correct me. Tell me how to pronounce things.” I was extremely eager to learn the language, and within a year I was able to really communicate. I realized that unless I speak the language I would be an outsider. Communication is a great thing, in good and in bad. You can really improve relations with anyone if you can express yourself, if you can explain what you want and what you don’t want, and that helps a lot.

Semler: What school were you going to?

GOLDEN: It was called Manual Arts in Los Angeles.

Semler: What did you see as the Americans’ feelings towards the US at that time?

GOLDEN: The time was at the end of the war, and the Americans saved Europe. Throughout the world the Americans were considered the ones who saved the world, really. You have no idea of the misery, the tragedy, the persecution that the Nazis brought throughout Europe. From country to country to country, all they did was kill, kill, torture, and take whatever the country had in food, in objects of art, lives, everything. They were like vultures wherever they went. Then the Americans … things changed. The Americans started to occupy all this, Americans and British occupied … the Germans started to lose the war, and things were not too good, so little by little they invaded France, they invaded Italy, so they went country by country. The hope and the prayers of every citizen in these countries were that the Americans should come and liberate. They were called “the liberators.” They were called “the saviors of Europe.” Unfortunately, after quite a few years, they all forgot about it. Time takes care of everything, really, whether it’s bad or good. We forget everything, but if they look back, if they can show some movies of what the Americans did for Europe in terms of good will and of help, material help and moral help … I don’t forget it. Maybe some people forget, but I do not. I have a very grateful feeling for the country, for the citizens, because they did a lot of good for the world at large. Whether they were Jewish or they were not, they helped everybody.

Semler: Do you have really strong feelings right now towards this country?

GOLDEN: Absolutely. America is my home. I’m an American citizen, a proud one. In times of shame, of wrongdoings by politicians … does a mother divorce the children when they are bad? No. Do the children divorce their parents because they committed a wrongdoing? Well, America is my mother, or I am the child of America let’s say, for better and for worse, so I am here. If I can do anything to ameliorate the situation, which in many instances is not perfect, especially through the last few years [in which] we have been going through ups and downs. If I can do something, my part, I will do it. But I do not say that nothing … I love America for better or for worse. This is my home. That’s all I can say. I would not want to live any place but in this country.

Semler: What kind of effect has the whole European experience had on your lifestyles, on the bringing up of your children, on your values?

GOLDEN: Generally, I’ll say we are more conservative. We have been going through a period of a very quick and radical change in the moral values, in the behavior of people, not only in the United States but through Europe, through Asia, everywhere except the Iron Curtain countries where they have no freedom. Any country which has freedom has come very fast. The progress has been good in some ways and rather shameful in others because in the name of personal freedom we have been doing things that, really, if we look down deep in our hearts, I can’t say that we are proud of. Through the style of life we have been … through progress again … we blame it all on progress: the mobility, the affluence of the citizens, the way of life. The center of life which was once the family is no longer the same. And when you break down the strength of the family base, it doesn’t lead to good things, really. Again I am referring to the time when for the sake of my sister I survived, and she survived for my sake. In other words, I think we have come far enough, detaching you know, families spreading here and there. I think if we can try not to lose contact with each other, in other words, to still keep the family ties sacred, strong before committing an act of wrong, whatever it may be, a little one, a big one. How would it affect my family? Maybe that could stop someone from committing an immoral act. Anything, whether it’s dope, whether it’s committing adultery. According to the Bible, we should not live out of wedlock, a man and a woman, and nowadays it seems like our society accepts it, or people choose to live so, saying “Well, it’s better to get acquainted first before we get married instead of getting a divorce.” Well, that’s one way to see it. I say don’t get married. You don’t have to live together. You don’t have to share the same roof. You don’t have to have sexual activity together, you know. You can talk clearly about the understandings of living together in wedlock, to know each other instead of rushing into marriage at a very young age, or rushing into marriage before being certain of each other. I’m not saying that this is only happening in the United States. It’s happening throughout the world, even in the Catholic countries such as Italy, where divorce was not permitted and now just recently is permitted. That’s an example; I’m not pro or against it. I’m not against divorce. If two people can’t get along well together, I think that probably the best thing to do is just get a divorce. I’m not against it. But on the other hand, I say that people should not rush into marriage.

Semler: That’s really a nice philosophy. Thank you very much. It’s been fascinating.

GOLDEN: Thank you.