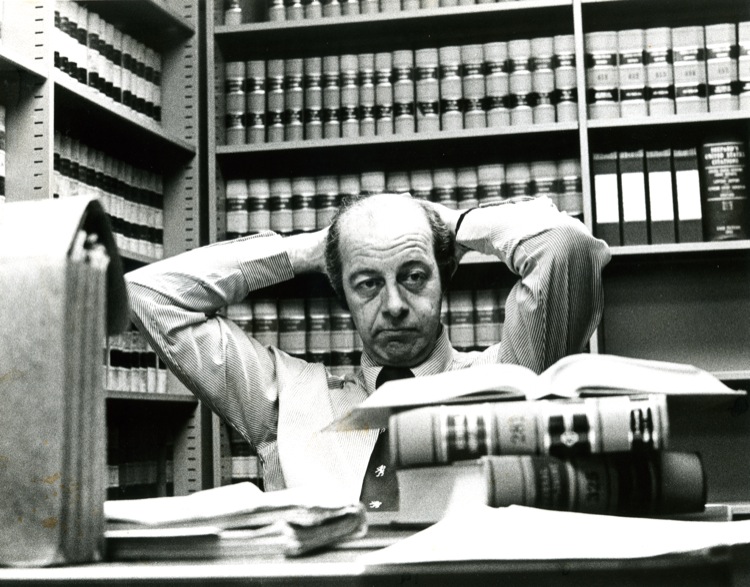

Jacob Tanzer

1935-2018

Jacob Tanzer was born in Longview, Washington in 1935 and lived there until his family moved to Northeast Portland in 1945. In 1953, he graduated from Grant High School. He earned a BA in 1956 from the University of Oregon. In 1959, Jake received his Juris Doctorate from University of Oregon School of Law, and in the same year passed the Oregon bar. He also attended Stanford University and Reed College.

In 1959, following graduation, Jake and fellow colleague Frank Granata established a small law practice in Portland, Oregon, Granata & Tanzer, and practiced law there from 1959 to 1962. In 1963, he joined the US Department of Justice, where he served as a Trial Attorney in the Organized Crime and Racketeering Division of Robert Kennedy’s Justice Department. In 1964, he was sent to Mississippi as a member of the Civil Rights Division that was investigating the deaths of three civil rights activists: Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. This case, which would later become known as the Mississippi Burning case, became instrumental in the shaping of the Civil Rights movement, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited racial segregation and extended full voting rights to all US citizens of voting age. The following year, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was also passed, which further outlawed discriminatory voting practices. Also of note, the case became a symbol of Jewish American involvement and support of the Civil Rights movement, as both Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were Jewish.

From 1965 until 1969, Jake was the Deputy District Attorney for Multnomah County, Oregon. In 1969, he became the first Solicitor General for the Oregon Department of Justice. One of his first responsibilities was to edit the briefs in Thornton v. Hays, the bill that preserves Oregon beaches for public use, for which he is unaccredited. In 1971, he became the first director of the Oregon Department of Human Services. From 1973 to 1979, he served as an appeals court judge for the Oregon Court of Appeals. From 1980 until 1982, he served as the 81st judge for the Oregon Supreme Court. He resigned on New Year’s Eve, 1982. After his resignation from the court, Jake returned to private practice in Portland.

Jacob passed away on July 23, 2018.

Interview(S):

Jacob Tanzer - 2010

Interviewer: Heather Brunner (also present is Judith Margles)

Date: April 20, 2010

Transcribed By: Anne LeVant Prahl

[recorder is started in the middle of an introductory discussion of what will be covered in the interview]

TANZER: … not a Jewish “hook” to my experience, except that I lived in a generally liberally oriented community, in which it seems Jews are disproportionately represented. If you were to ask me (and you are not) how did being Jewish affect your career or your life with other lawyers? I would have very little to answer. I would say I have had a tradition for example, my brother, who is not a lawyer was very early engaged in what we would today call civil rights work when he was fresh out of Reed and fresh out of the Army. He was in Germany as an infantryman when the camps were discovered. It’s hard to say except that we are all products of our –

Margles: – exactly, and by virtue of the fact that you have that sensibility within you, of course. You grew up in a Jewish home and you were instilled with Jewish values.

TANZER: I am not a religious person; I am totally non-religious. But culturally it is there.

Margles: Right. And perhaps this is what we can talk about. You can reflect on your schooling and your early years as a lawyer and whether or not being Jewish posed any kinds of barriers to you.

TANZER: It didn’t. It really didn’t.

Margles: OK. Well we certainly have encountered some stories about the quotas in the law school here and some lawyers felt that the only law open to them was collections and the “bottom feeding” parts of the profession where they were doing collections and bankruptcy. And it took a long time for them to –

Brunner: – and criminal law.

Margles: Exactly. They were going to the jails.

TANZER: Well the commercial lawyers, yes. But I think even that was much dated by the time I entered practice.

Brunner: That was in the ‘50s and early ‘60s.

TANZER: In ’59 I started. At Granata and Tanzer – an Italian and a Jew. That was our partnership.

Brunner: Yes, I was going to ask you. You mention in some of your articles that you had a practice before you went to Washington for a couple of years but you didn’t mention the name.

TANZER: Articles? Where did you find articles [laughter]? I think Lowenstein says something about me but that’s –

Brunner: – no, I have some great articles. A couple that you have written. And there are a couple of good quotes from you in them about being Jewish in relation to civil rights work. You mention seeing the Martin Luther King “I Have a Dream” speech.

TANZER: Oh, you read that?

Margles: I should say that I am just the wanna-be curator. Heather has been doing all of the work. Heather Brunner is really the brains behind this exhibit and she is really going to be –

TANZER: – just out of curiosity, where did you pick that up?

Brunner: Let’s see, there were a couple –

TANZER: – off the web?

Brunner: Yes. There is this one from the Oregon State Bar Magazine remembering the march on Washington.

TANZER: Oh yes. That was widely published, incidentally, beyond Oregon.

Brunner: It was very interesting.

TANZER: It was a great day. I loved that. God, I remember it like it was yesterday.

Brunner: You were working in Washington with the Department of Justice at the time, weren’t you?

TANZER: I was.

Brunner: And you volunteered as a marshal.

TANZER: There is more to it than that, and more interesting, but I don’t want to get into it. An afternoon isn’t enough. But my little group that I marshaled and got into place was right next to an area that was reserved for the American Nazi Party, which had advertised all over the south for people to come and have a counter demonstration. They were right next to the Washington Monument. I got to watch how they handled those guys and finally they moved on.

Brunner: Yes I was wondering from the article because it seemed to… I wasn’t sure if a lot of them showed up or not because you said they had moved on.

TANZER: Oh, did I mention it in the article?

Brunner: Yes.

TANZER: It was an interesting thing. If they were here, there were police and National Guard that made a cordon around them. One cop, one soldier, one cop, one soldier. There were only about half a dozen of them [that] showed up. Whenever anybody walked out, they would separate like an amoeba around that person, wherever that person went, and bring them back. There were eight or ten, or 12 of them. Nobody showed. They were expecting 100,000 and nobody showed so they just kind of slinked away after a while.

So it was my job to guard my group against these nefarious disturbers. I will tell you one story that has nothing to do with anything. One day the Nazis were out on the corner of 10th and Penn. There is a small plaza in front of the Department of Justice entrance. They were marching. The number-two guy was familiar to me. They had some complaint against the Department of Justice and they were very stern, picketing in a circle. I was thinking, “I ought to do something.” But I’m not going to slug the guy, you know [laughs]. I can’t do that. So I went up to the guy who was the second-in-command of the organization. I just fell in beside him as he was marching. And I said, “Your fly is open.” [laughter]

Margles: That is fabulous. A “peaceful protest.”

TANZER: That was one of my better moments, if I say so myself.

Margles: He probably never forgot this story either.

TANZER: I hope he didn’t. In any case, you have articles.

Brunner: I particularly like this one.

TANZER: Oh! Where did you get that? Did I send this to you?

Brunner: Judy forwarded it to me.

Margles: Oh, do you know Adair Law? She has done some writing for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. I think she does their newsletter. She found this article and forwarded it to us.

TANZER: Well I started writing this for my kids and then somehow it got longer and a little bit more literary.

Brunner: It is very interesting and very detailed about your work in Mississippi.

TANZER: Well this was the first time. I was down again in 1967, as a volunteer.

Brunner: That was another question I had for you. You were a District Attorney?

TANZER: I was an assistant, yes. I was a Deputy District Attorney. But the group I was working for was nicknamed the “President’s Committee” because Kennedy had a gathering and said, “What are you guys going to do about it?” And they formed this committee. It was called the Lawyers Committee for Equal Rights Under the Law, or something like that.

Brunner: Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights.

TANZER: Something like that. And that is a collection of stories too. But I haven’t written it yet.

Brunner: Well you could talk about it. We would be happy to hear about it.

TANZER: Oh, I tried a case against the local chairman of the White Citizens Council, which was sort of like the Klan with neckties. That was in Natchez in 1967. He was a Jewish guy. Jewish! Eichelberg was his name.

Margles: And he was a member of the Klan?

TANZER: No, this was a dignified group; a middle-class group. It was the equivalent of the Klan but they kept their hands clean.

Brunner: You had mentioned that as far as the Jewish population of the South went they kind of stepped away from it [the treatment of African Americans in the south at the time].

TANZER: They kind of ducked and let the waves go over.

Brunner: Yes, fearing that if it weren’t the Blacks it would be them.

TANZER: I’m no expert, but that was the common perception. Everything I saw was consistent with it.

Brunner: So that strikes me as odd that this gentleman would be the head of an organization that would actively pursue that. And you prosecuted him?

TANZER: No, it was a civil service hearing, which is quite unusual. The police had maltreated a black man. The Lawyers Committee filed a complaint and this was heard by the Civil Service Commission of Natchez, municipal. They beat the guy up and all that. The finding was (and this was revolutionary in that day) that the policeman had abused the man by calling him “horse,” which at that time and place was the equivalent of “nigger.” That was not proper and they suspended him for three weeks without pay. In those days, a small victory like that was a triumph. He defended the policeman.

Margles: Eichelberg did?

TANZER: Yes. He treated me with elegant, courtly courtesy (I wonder if those words are related). [laughter].

TANZER: So do you want storytelling? Do you want memories? What do you want?

Brunner: I have put together some ideas and some questions to ask you. We can see where it goes from there. I am going to go back a little farther too, maybe into your family.

TANZER: I think family, for both your purposes and my thinking, I go into it a lot. I think I refer to my brother in that [indicating an article].

Brunner: Honestly, I didn’t see anything about your brother in this and I would be interested in hearing more about your brother.

TANZER: I think I did. [begins to look over article and then reads] “My brother Hershal was an infantryman in Germany as the death camps were discovered. His first job out of college in ’48 was with a Jewish organization, the ADL. His responsibility was organizing public support for the legislative passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act.” As I understood it, New York had one and we were second, maybe third state for –

Margles: – for the ADL?

TANZER: And he was working –

Margles: – the ADL here was 1913 [upon review interviewee disputes date, possibly 1948].

TANZER: – with David Robinson Senior.

Margles: Right.

TANZER: He was hired with the purpose of getting that legislation through and building support for it. I went down to Salem and watched as Senator Richard Neuberger led it through the Senate. Hershal had really lobbied and talked to all the Kiwanis in southern Oregon to build support. My brother was nine years older than me. I was still just a kid when he was doing all of this and it was impressive to me.

Margles: So that had a big influence on how you saw things.

Brunner: What was your brother’s profession?

TANZER: He was a lumber broker.

Margles: I knew your brother, through the Jewish community. I knew him very well.

TANZER: My brother and sister-in-law were both really terrific people.

Brunner: I was just reading through your mother’s oral history interview that Shirley had done with her. I don’t know if you have had a chance to read through it.

TANZER: I have never read through it.

Margles: We will give you a copy. We can make a copy for you.

Brunner: She talks about coming out here on the train. They didn’t eat for six days because they were afraid to get off of the train.

TANZER: Yes, so they were hungry. I never met my grandmother. She died before I was born.

Brunner: It was your mother and your uncle?

TANZER: I think they came separately. My uncle came a little bit later. Uncle Ben Rosenfeld. I don’t believe he was with them.

Brunner: One of the questions –

Margles: – now I get it. Ben is Meryl Haber’s grandfather.

TANZER: Yes.

Margles: And he was your grandfather as well.

TANZER: No. He was my uncle. My mother’s brother. There were four brothers and my mother that came to America. There was also a sister, who with her husband, walked from the northern Ukraine (what is now Ukraine) to Palestine. Walked. My grandmother had about ten children, about half of which died.

Margles: OK I think I am fairly oriented now.

Brunner: Now this goes back to one of the themes of the exhibit. Your father was a tailor and he had a shop. A lot of the doctors and lawyers seem to have parents who were merchants. Do you have any recollection of how important education was to your father? Was there an emphasis placed on it?

TANZER: Yes, it was his first priority. Neither of my parents had been at school for even a day. My mother’s education was confined to looking over her brother’s shoulder when older people were there to teach my uncles to read from the Torah or to daven. She would sit on the steps and listen. That was her only education until she came to night school to learn English. It was the same for my father except that my father had been apprenticed out to a master tailor when he was ten. He hated it. He really did not like being a tailor at all. Some people have the impression that they had met in the old country but they didn’t; they met here. And that was his only education, his tailoring apprenticeship; so was education important? Yes, because they didn’t have it, they wanted it for their children. They saw it as the avenue towards what they would call “success” and what we would call a “happy life, a fulfilled life.” They didn’t know what education was, but they knew it was good and that their kids ought to have it. They gave both Hershal and me, as far as I could see, every encouragement. If I wanted to do something I had to explain it to my folks. If the explanation wasn’t very satisfactory, it didn’t seem to make them want it, I would say, “It’s educational.” [laughs] That was the magic word. If it was educational, I not only could but should do it.

Margles: Did you speak in Yiddish with your parents?

TANZER: I never did. “Speak English, Dad.” I truly regret that. One of my biggest regrets was that I wanted to learn Yiddish, and I didn’t know the difference between Hebrew and Yiddish as a child, and I went to Hebrew school thinking that they were going to teach us to speak the language that our parents spoke. It was a real let down to learn that all they were going to teach us to do was to phonetically read prayers. That was a disappointment; I never learned it and I regret it.

Brunner: Did you always know that you were going to go to college?

TANZER: Yes, it was just expected.

Brunner: For both you and your brother?

TANZER: Yes, although Hershal’s was interrupted. He was just waiting to go into the Army. He graduated high school in, I believe, 1943, in Longview, Washington. He went to Community College until he was old enough to go into the Army.

Brunner: And you went to Grant High School?

TANZER: That’s right.

Brunner: At that time there was a nice sized Jewish student population there.

TANZER: Yes, Northeast Portland was sort of the upwardly mobile area. Jews that had “made it” left Old South Portland and went to Irvington and Grant Park. We came from Longview and moved into Irvington. But my uncles, there were some in Old South Portland, some in Northeast Portland. They were moving to Northeast. Grant was an upwardly mobile school and Lincoln was the school for the still-immigrant class kids and also those that had kind of made it to the middle class. There was a mix there. Now obviously, that is a great generality, but that is kind of how it was.

Margles: So you didn’t live in South Portland at all?

TANZER: No. But I spent a lot of time in South Portland.

Margles: So did you go to Hebrew School at Neighborhood House?

TANZER: No, it was in a little house that they rented on NE 16th between Knott and Brazee, right behind the Irvington Grocery store –

Margles: – [simultaneously] oh, on the Eastside.

TANZER: Where, when I was in the seventh grade I think, the guy caught me shoplifting a candy bar. He took me in the back room and gave me my first lesson in the law. [laughter]

Brunner: Should I turn off the recorder?

TANZER: [laughing] No, the statute of limitations has passed. I’m OK.

Margles: Did he tell your parents?

TANZER: No, he did not tell my parents. That was my greatest fear.

Brunner: Sounds like they just took care of it on their own. Another thing I want to ask you about, from reading through your mother’s oral history was that your father, in Longview, had helped some of the German refugees. Some of the German families had come and stayed with you while they were waiting to be placed.

TANZER: That was very meaningful to me, even as a little kid.

Brunner: You would have been very young at the time.

TANZER: To orient you. I was born in 1935 and we left Longview in January of 1945. There were three families that they helped, the Mandlers, the Vorembergs and the Millers. They would stay first in our house for a little bit and then my dad would find them a place. There was work to be had because most of the young men were in the Army.

Margles: So we are talking ’37, ’38?

TANZER: Yes, the late ‘30s. I can’t be more precise. Mr. Mandler, Fred Mandler, he was a real story. He had actually been in Dachau and they had bribed him out. Then he came and lived with us for a few weeks. I have this memory as a little boy of Fred there in our bathroom in his undershirt shaving. Then a couple of weeks later his wife came. A place to live was found. And to jump ahead in the story, when we moved to Portland, the Mandlers did too. And my father had a little bit of money because he had sold his business. He bought a duplex for the Mandlers to live in, half of it, in Northwest. Fred opened a dry cleaning shop on 23rd and ultimately lived in the apartment above it (which is kind of a traditional story). Then, jumping way ahead, in 1974 approximately, I was on the Court of Appeals and I was asked to give a talk to the Oregon Justices of the Peace Association on Miranda, which was kind of a new decision. As I was driving to Monmouth to give this talk I heard on the radio that Fred Mandler had been killed in his laundry shop by a kid who turned out to be robbing him. A young, black kid shot him to eliminate a witness. And the idea of escaping from this organized brutality to come to America and then to be killed by random brutality was… I can’t philosophize about it but it was so striking. I remember I was quite broken up about it. My whole talk was about that. It was all spontaneous and gave me a chance to get it off of my chest. It was a terrible, terrible thing. Mrs. Voremberg (Elise or Else) was the secretary at Temple Beth Israel for many years.

Margles: I thought that name was familiar. Both of those names are very familiar to us.

TANZER: Gabi Miller became Jerry’s wife (I can’t think of his last name). Their families fit into American life and I was very impressed that my parents helped them get a start.

Margles: What were the circumstances that led your parents to pitch in? Your father was a tailor, was there a political motivation?

TANZER: No, my father was not political. But he came to Portland (you saw a picture of his shop on Third and Couch) and he tried to make a living as a tailor. He also had a bitter divorce from his first wife. He left thinking maybe he could make a better living somewhere like maybe Astoria. Oddly enough, they didn’t need a master tailor there so he went to Centralia. My mother was widowed young and somehow her brothers saw to it that she was invited to a wedding or something like that where my father was going to be. And they got together. There was fifteen years difference between them. My brother at that time was an infant. They then lived in Centralia. Centralia didn’t need a tailor either. So they moved to Longview, where I was born. During the Depression (this is a longer story than you want me to tell) a manufacturer in New York had to get rid of suits and shipped some out to Dad. He sold them and all of the sudden he was in the clothing business. He had a clothing store in Longview, Tanzer’s Exclusive Men’s Store. “Tell me, Dad, what does ‘exclusive’ mean?” He says, “Men only – no women, no children” [laughs]. So it was Tanzer’s Exclusive Men’s Store. Then he was diagnosed as having prostate cancer and so he sold the store and moved to Portland so that when he was gone his wife, my mother, would be near her family. And it was my father’s luck. He didn’t have it. It was a mis-diagnosis [laughs], so he opened another tailor shop at SW Third and Stark.

Brunner: So it was a connection through New York, is that was how he got involved with the German families?

TANZER: Oh, no. I suspect that was probably through the Joint or an organization of that nature. He was not political in anyway. No I shouldn’t say that. Roosevelt was a hero to him. But in Russia he was a socialist, an organized socialist in a little cell in his town. A telegram came through to the local guy, whom he called the sheriff, to bring him in for his socialist activities, to arrest him. Fortunately the sheriff’s daughter was also in the cell and the sheriff’s daughter warned him. He escaped, literally two minutes ahead of the Okhrana, which was the Tzar’s secret police. He was smuggled out. There were smuggling organizations in those days. That is how he left Russia. So he was political to that extent. In later years I asked him, “Dad, what is socialism?” He said, “Socialism is anything but the Tsar.” That was it for him. His real politics were that he was for the working stiff.

Margles: That is a brilliant answer. It is such a clear answer. It is so true. The Tsar was this isolated crazy man and then there was everyone else who worked in the country.

TANZER: And Roosevelt made him a Democrat. His first vote (I don’t know what year it would be), the local Democratic functionary came with him into the voting booth and told him who to vote for. Then took him to one of the bars down on Burnside and gave him a quarter for his dinner and that was his first vote. That was democracy. So he was very apolitical. But then when Roosevelt came in he was, he was God.

Brunner: I think you can probably consider your father as one of your influences or mentors in a way.

TANZER: Mentor is not the right word, but influence certainly.

Brunner: [laughing] I’m trying to segue into another question.

TANZER: Obviously he meant a lot. The idea of being for the working stiff. I was thinking even in law school, “Maybe I want to be a labor lawyer.” It didn’t happen.

Brunner: You talk about your cousin Sol Stern and Morrie Sussman as being influences for you. Was Sussman one of your cousins as well?

TANZER: No, Morrie was a cousin by marriage. Gilbert Sussman was not related to me except that he was Morrie’s brother but he was very supportive of me when I aspired to go to the court. He was both morally supportive and offered some financial help. I was very appreciative of that.

Margles: Sol was your cousin?

TANZER: He was married to my cousin. They were both married to daughters of my uncle Moishe.

Margles: Thank you. I didn’t realize that connection.

Brunner: So were they influences to you also when you were younger?

TANZER: No. It was just that they would come to family parties and they just seemed like such terrific guys. “Yes, that is who I want to be like.”

Brunner: Is that what made you choose to go into law?

TANZER: Yes. In seventh grade I decided. It was not logical [laughs].

Margles: Did you really? You knew in seventh grade?

TANZER: Yes. In seventh grade I decided to be a lawyer. Why? No real reason except I thought that those two guys were… I couldn’t have articulated it, but they were people to emulate.

Margles: Sol Stern for me is… there are a number of people who I obviously never met and he is someone from what you hear about him he was just an extraordinary human being.

TANZER: Yes, and so was Morrie. Morrie was a little quirkier, but he was a guy of great strength of personality and conviction.

Brunner: Gilbert sounded like a smart man, too.

TANZER: Oh he was a smart man and a good lawyer, a solid lawyer. They had a third brother, Ben, who was a CPA.

Brunner: Do you know what kind of law Sol practiced? You said you were considering labor law.

TANZER: I think he was a general practitioner.

Brunner: You considered labor law because of your father’s leanings?

TANZER: Yes.

Brunner: When you were in law school, what was your specialty?

TANZER: Particularly in my day you didn’t think so much of specialties. I just went to law school to learn how to be a lawyer. I didn’t give –

Margles: – where did you go to law school?

TANZER: – it too much thought. University of Oregon.

Margles: You went to the U of O.

TANZER: I wanted to go to Stanford and it was a disappointment. I couldn’t raise the dough for it. But Oregon was OK. It was a funky little law school. It wasn’t much in those days. It has grown into a fine institution. But I didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted to do. I thought about that. I thought about criminal law, as a defense lawyer. I was very naïve.

Brunner: That was one of the things I thought about while reading. I guess these days, when you go into law school you go in with the idea that I want to focus on litigation or business law or intellectual property law.

TANZER: Yes, I think that is more true today. Probably even today you couldn’t make a generalization. There are people who do and people who can’t think of what else to do so they go to law school.

Margles: Did you, at the University of Oregon… So you went there long after the war ended, there were no quota systems. Did you hear stories about discrimination of Jews at the law school?

TANZER: No, I didn’t. I never heard that. We had some of the first women to be there and they were treated with cool, correctness by the dean. The guys welcomed them [laughs]. They were neat. I still like them. They are wonderful people. But the dean, to whom I’m sure it didn’t seem quite right, handled them correctly.

Margles: So there was nothing… I mean, I wouldn’t think so.

TANZER: Never heard of a problem. As a freshman, I wasn’t able to join the non-jewish fraternities, but frankly that didn’t bother me much.

Margles: It was an expectation, right? That the fraternities just weren’t there for you?

TANZER: Well…

Margles: Where did you do your undergraduate? Were you at Reed?

TANZER: I was a freshman at Oregon. I was a sophomore at Stanford. I was a junior at Reed. In those days you could go to law school after three years.

Brunner: That is where my confusion was. I didn’t know that.

TANZER: I didn’t care for Oregon. I transferred to Stanford, which I loved, and I really blossomed there. Then my mother got TB and that depleted the treasury and I had to come live at home, so it was Reed. That is how it happened.

Brunner: So your parents put you through school. You didn’t have to work your way through school?

TANZER: I had to work all through school. I got a lot of help from my parents, particularly that year at Stanford. They helped me some with Reed, and they gave me a home. In law school I was pretty much on my own. They helped me out a little bit but I was pretty much on my own.

Brunner: How did you make your way through law school? What kind of jobs did you do?

TANZER: Oh, I was a janitor and I helped with food in the sorority houses so I would get my meals that way.

Margles: In the sorority? With the girls?

TANZER: Well it wouldn’t be right for them to have a non-member girl serving. “Hasher,” that’s what we were called. And then I took summer jobs, obviously, of all kinds. I worked for my uncles, two of them, a couple of the summers. Once in the junk yard and once in the mattress factory. That was Uncle Abe and Uncle Ben. Then I worked for Container Corporation making boxes and then I spent three summers working for the county grounds doing all kinds of manual labor associated with landscaping. That was when I was in good shape.

Brunner: You mentioned in one of your articles that you just recently found out that your cousin Morrie had worked with Japanese interns.

TANZER: My cousin Morrie Sussman. I really don’t know what he did. I learned it from his son Howard, who is still on the faculty at Stanford Medical School.

Margles: Yes, he comes by occasionally.

TANZER: Oh? He would show up for his family’s funerals and now that generation is just about gone so I don’t know how much we will see of Howard, I am sorry to say. I have visited with him down there. Anyway, I just heard generally from Howard that that was true. I didn’t really know it at the time.

Brunner: OK, moving forward a little bit, when you got out of law school you started the small practice with…?

TANZER: Frank Granata, who was ahead of me by a couple of years in the law school. We decided to go into practice together. Our filing cabinet, if you looked at the clients’ names on the tabs of the files, were mostly Italian.

Brunner: What kind of law did you practice when you first got out?

TANZER: Whatever walked in the door [laughter].

Margles: Did you want to join a large firm?

TANZER: I had no great desire to join a large firm. I investigated it. My grades weren’t particularly good. In fact, I graduated as the top man in the bottom half of my class [laughs]. I’ve always been pleased with that. I don’t know why. So there is hope for anybody. So I wasn’t large firm material. I interviewed with a few smaller firms but nothing I felt particularly comfortable with. I was, to a large degree, something of a romantic. The idea of hanging up my shingle with my friend appealed to me. I got tired of it, though. It became routine and I didn’t care much for that. That is when I started looking at Washington.

Brunner: What made you decide to go with the Department of Justice, to make that big leap?

TANZER: Well, drafting wills, for example (which is much more complex today) was a puzzle. So the first time you solved that puzzle and learned how to do it, it was very interesting. And then the next time it was not that interesting. And the next time it was kind of dull already. That was how it worked for me. So I was getting kind of bored with what little we had to do. We weren’t getting rich, I assure you. And at the same time the Kennedy administration had come in with the “New Frontier” and all that. Again, being something of a romantic, I thought, “I would like to be part of that.” I had good connections at the Department of Justice, namely my old high school classmate Jack Rosenthal, who was well-placed at the Department. I think Jack was some help to me in getting on. Bobby Kennedy was Attorney General and my choices were that I wanted very much to be in the Civil Rights Division and failing that Organized Crime and Racketeering Section. As it turned out, in the Civil Rights Division there was simply no opening. They did hire me, and Jack must have had something to do with it because my qualifications were not that great and the department was very selective. But in any event I did get on Organized Crime, which was Bobby’s pet organization within the organization so we worked a lot with Kennedy. It was a heady thing to do. And compared to a corner office on 122nd and Glisan it was wonderful. It was terrific. I loved it.

Brunner: What were some of the cases that you worked on with the Organized Crime?

TANZER: Well, there was one labor racketeering case where we went after Richard Gosser, a senior vice president of UAW International, which was an otherwise very clean union. But as Amos Reed, who later worked for me used to say, “He was a black feather in the angel’s wing.” And he was that. He was guilty of indirectly, through others, buying information by corrupting a secretary in the IRS office. He was essentially buying reports of his investigation. I made that case and was quite a hero to the IRS for a while. So I was a favorite lawyer, but not a tough, grizzled old prosecutor. I was around 28.

Margles: Were there any cases that touched on Oregon that you worked on?

TANZER: I did a few grand juries in Oregon, dealing primarily with gambling, but nothing much. I went for it just so I could get a trip home. That is where I met Norm Sepenuck, incidentally. He was also here on assignment. We met here in Oregon, both on assignment from Washington, D.C. He is an interesting guy. He has been working at the Hague for the last few years dealing with the Bosnian War criminals.

Brunner: That was one of my questions, when you transferred to the Civil Rights Division from Racketeering. That was originally where you had wanted to go.

TANZER: Yes, it was. Originally the jurisdiction for the murder of Schwerner, Cheney and Goodman was with the Civil Rights Division. The idea that that could be a Federal crime was kind of a new thing and the pressure was on. And Hoover finally jumped into it with the F.B.I. He had resisted that over the years. It didn’t come to the Criminal Division; it was Civil Rights Division that was handling it. The F.B.I. investigation, as I have written had hit a dead end and they need somebody with Grand Jury experience. I had done a lot of Grand Jury work. Originally they had chosen Henry Ruth, who later became one of the Watergate Special Prosecutors. A wonderful guy and good lawyer, he was one of my office mates in the Organized Crime Section. All of a sudden another responsibility came up for Henry and he was out. When I heard that he couldn’t do it I just jumped at it. I thought, “I want to do that!” They accepted me. I interviewed with John Doar, Burke Marshal, Bob Owen and they agreed so I came on.

Margles: What year was this?

TANZER: That would have been ’64. They [Schwerner, Cheney. Goodman] were killed in June of ’64 so this would have been August or September.

Brunner: Reading through the articles I see that what you had done was pretty innovative at the time, the [14th] amendment and using the law from the Reconstruction Era.

TANZER: [laughs] We never told them it was a Reconstruction Era law!

Brunner: That’s right, you just say, “It’s been on the books a while.”

TANZER: That’s right [laughter].

Brunner: How did it occur to you to put those things together?

TANZER: I take no credit for it. I talked to Bob Owen, who was the head of our team and a legendary fellow in the department. I said, “Bob, maybe we can prove the murder but where is the federal crime?” And that was Bob’s thinking, that for public officials such as the sheriff to deny someone his rights guaranteed under the United States Constitution was a crime under this old statute. So I take no credit for it. I did write the indictment, which was later upheld by the Supreme Court so I felt good about that.

Brunner: That must have been a very charged atmosphere down there at that time. Were you down there by yourself? Was your wife with you?

TANZER: I was there by myself in terms of family but it was a Department of Justice team. Bob was the chief, I was at his right hand, having had grand jury experience and criminal experience and then there were probably about five or six young lawyers from around the Civil Rights Division. We came to our plans and fanned out into the cotton fields to work up witnesses and find witnesses, decide who to use and prepare them.

Margles: Were you fearful of your safety?

TANZER: You know, that is often asked. I really never was. I don’t think any of us were really. But we were careful, not being in Neshoba County after dark. Repetitious for those who have read my little story, I remember Jim McShane, the Federal Marshal called me into his office before I went down and showed me – he had just been through the James Meredith admission to Ol’ Miss – he showed me the crease in his white helmet. That was a true insurrection. There were a lot of people injured in that and I think even a couple of people killed. “It’s dangerous down there,” he warned me, “Be sure to be careful about pick-up trucks with guns in the racks.” And when we got down there most of the vehicles were pick-ups and they all had gun racks, and they all had guns in the gun racks. But we were careful about being there after dark. After dark we always had other things to do. But I was never really scared. We just weren’t thinking that way. We had a job to do.

Brunner: How did your wife feel about your being down there knowing what was going on?

TANZER: She was… We had a very bitter divorce but one positive thing I must say was that she was very supportive, always, of that kind of activity. That was true in 1967 also. She thought it was the right thing to do.

Brunner: I was reading that the purpose of the grand jury was “not to indict the guilty but revive the investigation by stirring the pot. To give the impression that we were closing in so that the conspirators and witnesses might be made nervous enough to save themselves by talking to the police.”

TANZER: And that is what happened. Not to the police, to the F.B.I. The conspirators were the police. [laughs] That was the problem.

Brunner: Did you find that the Organized Crime and Racketeering Division helped you in being able to do that? To rile them up and make them nervous?

TANZER: It trained me to think like a prosecutor of big cases and to use the grand jury as an investigative tool, yes. That is why I was there. I had just had a big case with a lot of grand jury work and many search warrants and arrest warrants, many people indicted. We had essentially arrested and convicted, after a lot of grand jury work, the entire numbers racket in Cleveland, Ohio above the street-runner level. So much so that the Licavoli Mob in Detroit had closed down their gambling, ironically, until the end of the Kennedy administration, which came very soon after that. So I had done a few things which I had thought were, I’d like to say exceptional except that other guys in the unit were doing great things, too. But they were clearly activities which would prepare a person for this kind of work. They were right finding somebody who really understood grand jury work and our section was the place where that was true – where those people were.

Margles: Did you have any sympathy for what was going on in Mississippi? Did you try and understand the other side? Did you ever read Elinor Langer’s Book A Hundred Little Hitlers? It is a really interesting book about the Mulugeta Seraw murder. She really looked at these skinhead kids and tried to come to an understanding of who they were and why their actions were as such. It wasn’t an entirely unsympathetic work.

TANZER: Well, I never ran up any sympathetic feelings about the people I was investigating at all, but I had a very deep emotional reaction and feelings about the rural Black community that I dealt with. They were people of enormous courage and character and depth just totally unrecognized by the society they lived in. Their cooperation with us was really courageous. I developed a huge respect for them and affection for them.

Brunner: Did the government offer them any kind of protection for their testimony or did they just come forward because they wanted a change?

TANZER: No, not really. It would have been unrealistic to offer protection. My witness, Mr. Cole, I finally asked him why. “It takes a lot of courage for you folks to cooperate with us. Why? What is driving it?” Mr. Cole said something like, “Them boys, they was just trying to help us. They had no cause to kill those boys.” He said it just about that way and I heard that a couple of times. It was enough. They had reached the tipping point so they cooperated with us. Before that they would never have said a word. That impressed me.

Brunner: You said you had developed an ulcer.

TANZER: Yes, well now they say it is bacteria.

Brunner: Right I have heard that.

TANZER: Who knows?

Brunner: Exactly. But you still became involved with the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights.

TANZER: Well I went down as a volunteer. I was looking for a way to get back and that was a good way to do it. George Van Hoomissen was the District Attorney, who I’ll see tonight, is still a good friend. Actually he had a few of us deputies go down at various times, including myself.

Brunner: From what I’ve read about it, it was a two week commitment to go down?

TANZER: It was usually a month. I was there for a month.

Margles: And it was all pro bono?

TANZER: Oh, yes, sure. Oh, they probably paid my airfare.

Brunner: Did you feel that month’s time was enough to go down and do something? I know later on it says that it was more like two-week commitments from different lawyers going down.

TANZER: I don’t know where the two weeks is coming from. It was generally a month, or somebody might go down for a couple of weeks to handle a case. But it was generally a month.

Brunner: Would you personally go down to handle a case or did you…?

TANZER: No. I went down to handle whatever came up.

Brunner: What kind of things came up?

TANZER: Oh, I mentioned the police hearing in Natchez. I had a case involving the NAACP boycott of downtown, and Hattiesburg. That was a great case, a white guy had too much to drink and goes down to the Colored Quarter, as it was called. He picks a fight with a black guy and the black guy backs off. A black guy doesn’t hit a white guy in that time and place. So he called him names and tried to start up a fight – it didn’t happen. He went away, drank some more and came back down and started taunting the black guy again and hit him. The black guy hit him back, which is practically a capital offence in Mississippi in that day. And so the guy went to the city attorney and filed a complaint against him, the white guy did. And so the black guy filed a complaint against the white guy. Well! That was unheard of. At that time, in Mississippi, if the prosecutor refused to prosecute a case you could retain a private lawyer to prosecute the case for you, criminally. So I became the prosecutor in that case for the black guy against a white guy. I called ahead and I said, “I want the black side of that jury room full of polite, black people.” The NAACP saw that that was done. So one side of the courtroom was jammed full of quietly watching people. The other side was fairly empty, no whites. The judge saw these two complaints in front of him and the city attorney at one table and me at the other and said, “Gentlemen, come on up to the bench.” We did and he said, “What the hell is going on here?” [laughs] We told him. And I was generally treated with correct, professional courtesy.

Margles: By the judges?

TANZER: Generally, not always. And he said, “Don’t you gentlemen think you could step out in the hall and figure something out better than this?” So we did. We talked. He said, “Have him plead guilty.” And I said, “Sure, if your guy pleads guilty, my guy will plead guilty.” But he didn’t like that. We finally agreed to mutual dismissals. Both sides would be dismissed. This seemed to me a very ordinary day’s work. The kind of thing that happens every day. But there, that didn’t happen. That was unique. We went back in and so reported to the court. “So ordered.” “Dismissed” “Dismissed” And I went back to the NAACP headquarters. A wonderful thing down there was that a little victory was a tremendous event, any little victory. This thing, which would have been just a workaday thing in Portland, Oregon was a huge cause for celebration, It was the first time anybody could ever remember an assault case, or any kind of case with a white against a black being dismissed. There was music and there was dancing and I think there was a little bit of alcohol flowing. They were having a real party at NAACP headquarters and we had a really good time.

Margles: That is a great story.

TANZER: They weren’t big, landmark cases. They were little cases, but they were important to the communities.

Brunner: That had to be so gratifying, too.

TANZER: It was. And it was fun. When you win. [laughs] I also went down there on the downtown boycott. I lost 26 cases in one afternoon.

Margles: Oh my! [laughter]

TANZER: Which is a record that I hope will stand. For, you know, blocking the sidewalk, that kind of thing. We would try them in municipal court just on the way to an appeal to the circuit court. I didn’t stick around for that.

Margles: Back to the night of the party. The NAACP weren’t concerned that the white mobs would come?

TANZER: Well, they didn’t. No they weren’t. I didn’t have any sense of that.

Brunner: You had said, particularly during the Mississippi Burning trial, that if it had been tried at the time they would have gotten away with it but by the time it went to trial that you had noticed the change.

TANZER: That is really true. I was there with the Lawyers Committee in August of ’67. The trial, after the Supreme Court reinstated the indictments from the ’64 case, was set for September, 1967. In Judge Harold Cox’s courtroom, who had called one of the lawyer’s committee lawyers and ape or a monkey or something like that; he was very disrespectful of them – but he was part of the Mississippi Establishment. That was the word we got. The Establishment thought, “violence is bad for Mississippi.” It was not a moral thing; it was not bad for the people. It was bad for the image of Mississippi. So they went to trial in 1967 and there were convictions. But it couldn’t have happened before.

Brunner: They kind of shot themselves in the foot, too, by demanding a new jury, didn’t they?

TANZER: That is the irony.

Brunner: I don’t understand why they would have done that.

TANZER: That is the irony. Delay worked against them.

Brunner: And it changed the whole complexion of the jury, too. It was more integrated after. It was the guys on trial who wanted the new jury.

TANZER: Yes, they had moved to dismiss the entire case that the Judge Mize, I think it was dismissed. So that worked its way up on appeal to the Supreme Court. It took three years. And it came back for trial because the indictment was reinstated. It was a wonderful irony.

Brunner: You have a picture in this one article of the guys sitting there and they have just the smuggest looks on their faces, the guys who were indicted. I will show it to you.

TANZER: That was from Life Magazine. It was, at that time, a very famous picture.

[they look for the picture]

TANZER: That was when they showed up for their arraignment.

Brunner: Just absolutely no concern that they might be convicted.

TANZER: It was a game for them, and then it got serious.

Brunner: All right, I’ve been keeping you here all day but I do want to talk about your Oregon experience.

TANZER: I came back home in November. We voted for Lyndon Johnson with the motor running, essentially, and left for home.

Brunner: When you got home you were Deputy…?

TANZER: [sneezes] I was deputy DA for George Van Hoomissen. Not much to say about that.

Brunner: Right. Was it your work with civil rights that got you that ‘in’ to the Deputy District Attorney?

TANZER: Well, yes and no. George wanted an experienced trial lawyer, an experienced prosecutor. I was that so I didn’t have a problem with that. And I didn’t start out with a lot of misdemeanor cases. And then after not terribly long they consolidated the appeals so instead of each D.A. handling his own appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court or the Ninth Circuit, they consolidated to one person. I can shorten it down for you. When Lee Johnson became Attorney General he reorganized the Oregon Department of Justice into a modern law office. He deserves a lot of credit. It had a Civil Division, a Litigation Division, Tax Division, etc. and an Appellate Division. He hired me to organize that division and to head it. That is how it was formed. He did that in large part because he wanted to bring all of the District Attorneys’ appeals into Salem to be handled centrally by people who were expert in appellate work. He thought I would be credible because I had done that work in Multnomah County. I had done a lot of lecturing to DAs and things like that. That was how I went to Salem. The same day I started, the Court of Appeals was initiated with Judge Herb Schwab organizing it. That is a whole story too. Herb Schwab, a Jewish fellow, incidentally, was the greatest judge I ever worked for. When you used the word “mentor,” he is the person I would describe as my mentor. He was great.

Brunner: In what way? What did you get from him?

TANZER: I tried my first criminal case in his court room as a defense lawyer. I tried my first civil case before I went to Washington to Herb Schwab when he was a trial judge. It just worked that way. And I had a rapport with him. It was the kind of thing where we would finish each other’s sentences. The other lawyer would kind of watch us like it was a tennis match. I loved Herb Schwab and I flatter myself to say that my mind worked in much the same way as his. I hope I retain some modesty when I say that because he was great. I was not in his league. He was great because he combined intellect and practicality and pragmatism. He wouldn’t go off onto intellectual riffs that didn’t matter. He wanted to decide the case and decide it right and decide it quickly. He was so sensible. Do you want me to take a minute and describe a case briefly?

Brunner: Please.

Margles: Please. Absolutely.

TANZER: This was his opinion. A school district laid down hair length rules. In those day, with hippies and all that, hair length was a very controversial thing. Anybody with long hair “had to be a troublemaker.” So schools and police and others were setting hair length regulation. So the ACLU or somebody challenged the school’s hair length rule. How do you analyze a case like that? There is no law about hair length. Herb says (he wrote the opinion and listen to the elegant simplicity of this), “Every governmental body is created by statute. The statute gives it power to do certain things and to do all things that are reasonably calculated to accomplish that objective. The statutory purpose of a school, that for which it was created, was to educate children. There is no showing in the record that length of hair affects its performance of that function. Therefore, a school doesn’t have that statutory power.” Now isn’t that elegant?

Margles: Eloquent.

TANZER: Isn’t that simple?

Margles: My husband would have loved it?

TANZER: Your husband is what?

Margles: Well, he had long hair in high school and he said he got pinged for it in Columbus, Ohio.

TANZER: Well there you go. But that was how his mind worked. He did not intellectually complicate issues. He reduced them to their essence, to what really mattered. That was him.

Margles: Schools are there to teach and who cares? Yes.

Brunner: What year was that?

TANZER: It was about 1969 when I became Solicitor General, as it was called. It was a title I always felt was much too grandiloquent. I felt self-conscious about it. Then I went from there to what is now called the Department of Human Services, which I formed. After two years of that I told –

Margles: – you were counsel for Human Services? Or you were the head of it?

Brunner: How did that come across your desk? Going from being the first Solicitor General to …?

TANZER: Good question. It has to do with politics largely. The idea was to form one agency out of many, separately operating human services agencies: Welfare, Children’s Services, Corrections, Mental Health, Vocational Rehab, etc. I had been in a position, I was high enough in the Department of Justice where if there was a problem of some sort the Governor would… I would be part of a meeting with the Governor. Like how to handle the anti-war protest at Portland State, that kind of thing.

Brunner: This is Tom McCall you are talking about.

TANZER: Yes, this was an example. I was at the legislature frequently testifying about measures in Criminal Law or other public law. So I had become known. I was thought of positively. The governor wanted his assistant for Human Resources, as it was then called, to be the first director. He, however, got his sixteenth vote in the senate on a promise not to appoint that person to the job. So he had to have a “good” appointment, in a political sense. I was very politically acceptable but what did I know about running an agency? Not much. I would be accepted by the legislature so he appointed me and had confidence in me. I took the job with great misgivings. One condition was that I accept the guy he had in mind as my deputy. I did a lot of fast learning. One would think that I would become the mouthpiece and he would be manipulator but it didn’t work that way and he didn’t want it to work that way. It sounds immodest but I was the intellectual force and the political force that gave it political acceptance. The legislative leaders always said, “We’ll see how it works for a couple of years. We can always take you apart again in the next session.” There are various achievements I can talk about there but that would take a long time. After two years of pulling it together, of giving it a basic philosophy, of publicizing it around the state so that people knew what it was, of developing systems for integrated service by the agencies, the systems and facilities, (for example, we had a Chemeketa Community College campus in the State penitentiary), that kind of bringing things together.

Margles: Were you in charge of the state mental hospital?

TANZER: Yes, that was part of the Mental Health Division. That was part of my jurisdiction. I don’t remember where I was going with this. But I did that and I felt great about it. I was very happy with it. But after our first session in the legislature was over and I had established credibility on behalf of the department with the legislature, which was a long story in itself that I will not detail you with, I went back to the governor and said, “Tom, it’s time for me to be a lawyer again,” and he said, “Would you like to be a judge?” and I said, “Yes I would.” “Circuit Court or the Court of Appeals?” That was a hard decision. I was instrumental in the formation of the Court of Appeals, in the design and development of what it was going to be. I was on the committee that designed it. And I said, “the Court of Appeals” and that is how I wound up there, the first vacancy. Actually, the legislature created a sixth position.

Brunner: Did they create that position for you or were they already on the way?

TANZER: No. And Herb was Chief Judge.

Brunner: Wow, so you got to work with him.

TANZER: Yes. He was my chief. I had argued cases… I argued more cases to the Oregon Supreme Court than any lawyer in its history. So I was very… For me appellate work, even being a judge, was like swimming in warm water. I knew the business. But Herb –

Brunner: – what was it like being on the same side of the bench with him?

TANZER: I really liked him. He was wonderful. As I said before, I loved the way his mind worked. That always appealed to me. And we became more personal friends in that capacity and that was quite wonderful.

Margles: Was Muriel his sister?

TANZER: Mildred. She was on the City Council at that time and the two –

Margles: – the was a trained lawyer.

TANZER: – the two of them were on the telephone every morning.

Brunner: Really? She is quite an interesting character, too.

TANZER: Yes, Herb was a big picture guy, always asking, “How does it all work? How does it fit together?” And he said of Mildred that she would go to the beach and pick a grain of sand to criticize. [laughs]

Brunner: So you were on the Court of Appeals for awhile and then you got appointed to the Supreme Court. But you were only there for two or three years before you retired.

TANZER: Three years, and I didn’t retire, I resigned. That is a long story. I want to start with something though. I want to start with the appointment because there is somebody who deserves some credit for that. I was thought of as a liberal because I had done Human Services work. And I was a Democrat. That was for sure. Even though I worked for Republicans, I was a Democrat. And I was Jewish. And I was appointed to the Supreme Court by Governor Vic Atiyeh, who was thought to be a conservative by the standards of the day, a Republican, Arab-American. I have always thought that was very much to Vic Atiyeh’s credit. I admire him for it. I see him rather regularly and always enjoy seeing him. I think I am going to see him tonight. I thought that was the way politics ought to be. But you asked me why I left.

Brunner: Yes, but hearing how you got there in the first place from the Appellate Court. Was that just the next logical step? Was it the time and you felt…?

TANZER: Well there were a lot of good people. I had made a good record in the Court of Appeals. I say modestly, but I had. I had written some of the more important cases, particularly in administrative work, in governmental law, which turned out to be a field that I really worked well in and had a feel for. As did Hans Linde, who was on the Supreme Court at that time.

Margles: So when you joined the Supreme Court he was already sitting on it.

TANZER: He was already there. By the way, in law school, my senior year I took constitutional law. That was the year that Hans was out with tuberculosis. Whenever we had a disagreement Hans would say, “Jake, if only I had had you in my class.” [laughter]

Brunner: That could have changed your whole approach.

TANZER: Oh, we had a lot of arguments, Hans and I did, but they were always extremely respectful. But I should tell you, the reason I left after three years. I am not going to go into it but all of the sudden I had some severe financial requirement dealing with my first marriage. I had to make some money. So I resigned three years, almost to the day, after I had joined the court.

Brunner: You know, your saying that actually reminds me of a quote from my own personal reading. It was from Portland Monthly’s Best Lawyers. One of the lawyers, Nancy Moriarty had said in regard to salaries for Federal and State judges, they “have failed to keep up with the salaries for attorneys in private practice. And Federal judges have not had a pay raise in almost two decades. The court systems are losing judges and highly qualified candidates are not seeking judicial offices due, in part, to the low salaries.”

TANZER: Yes, Oregon’s judges’ pay scale is 49th out of the states. But I never complained about that. In fact some judges wanted me to make a big point when I left but I didn’t. I figured that if the pay is not what you want then you don’t take the job. I wasn’t going to go out on a bitter note.

Brunner: Do you think that it is true that this is affecting the kinds of judges that Oregon is getting?

TANZER: Yes and no. There are a lot of people who would not consider the court who would be very good judges. What it has led to is that some imbalance of government lawyers who did not have big buck salaries. Yesterday, for example, the Oregonian endorsed Jack Landau, who had been Deputy Attorney General (if not, then he was high in the Department of Justice). Well there are a lot of Department of Justice lawyers there and they are terrific judges. Jack Landau is a really outstanding judge. So it doesn’t hurt but somehow it seems that there ought to be a better balance. There are also those who come from private practice who are willing to take the cut because the money is not as important as the professional satisfaction. You find some of those there, too. And an occasional academic. So I think generally the judges are of good quality but it is not as diverse a group as it might be.

Margles: So you went back into private practice.

TANZER: I did.

Brunner: Was this before? You are still doing conflict resolution?

TANZER: Yes. I started doing that really thinking that at some time or another I would stop practicing law actively. I started building this little sub-specialty while I was in private practice. You can’t make much of a living as a lawyer in a law firm, with overhead, doing ADR work. So few of them do it, at least as a major part of their practice. But I knew that someday I would want to leave practice and do that on a part-time basis. That is what I have done.

Brunner: When you first came out of the Supreme Court you went into a law firm, didn’t you?

TANZER: That’s right. I went to one firm for a few months and that didn’t work out well. The firm actually disintegrated. Then I went to work with Ball Janik, which was a very happy relationship for almost 20 years.

Brunner: What kind of law were you practicing at that time?

TANZER: Business litigation. Business meaning everything except marital and personal injury work, although I did a little bit of that. Every once in a while that would come up. And a lot of government-oriented litigation – both for and against governments or units of government.

Margles: Were you a litigator? Did you argue before the Supreme Court?

TANZER: Yes.

Margles: Was that odd?

TANZER: Yes [laughs]. And the Court of Appeals.

Margles: For Ball Janik was it an asset to have you argue these cases before your former courts? How did that play out?

TANZER: In terms of marketing, yes, it was definitely positive. “This guy knows the appellate business.”

Margles: Did you win?

TANZER: Well, actually I won the largest judgment ever won in Oregon on appeal. The SAIF case. Alsea Veneer v. State of Oregon. The legislature had in around 1980, short of funds, raided the State Industrial Accident Fund (SAIF) saying that it had too much money in it and put it back in the general fund. A lawyer sued to return that money to the fund, which means it would go back to the employers who pay the premiums. He lost. He lost pretty badly. I took it on appeal to the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court and I won. We settled that case finally for 225 million dollars plus attorneys’ fees, which was, at that time, the largest judgment ever won in Oregon. One of my partners, shortly after I left the firm, was the lawyer who beat that record. I think that was a half-billion dollar judgment [laughs]. It was nice to keep it in the firm.

Brunner: I know we have taken so much of your time and there are still a couple of things that I haven’t asked you about.

TANZER: Why don’t you ask me what I did at the Department of Justice in Oregon?

Brunner: I do want to know about what you have done with the Department of Justice; that was one of my questions.

TANZER: I thought you might want it for your history. Before I was even on board, Lee Johnson had hired me but I was still working for the DA, the challenge to the public beach law was being readied for the Supreme Court. The first work I did for the Department of Justice was that before I got there, in my evening hours, Lee (who was not satisfied with the brief) had me rewrite the brief. My name is not on it. The highway division had it and they had a whole lot of theories that they offered and I pared it down to a couple of theories. I didn’t think you should give them a smorgasbord.

Brunner: The Schwab approach? [laughter]

TANZER: That is the Herb Schwab approach. And sure enough we won on my theory. I was very proud of that, if you talk about accomplishments that I am proud of. The first case I actually handled in the Department of Justice was for Beverly Williams, who used to be a news reporter on channel 12, a Black woman. It established that the Bureau of Labor and Industries could award mental anguish compensation in cases of racial discrimination. I was pleased with that.

Brunner: Was she dismissed from her position?

TANZER: No, this was a rental problem. A person wouldn’t rent to her, an apartment.

Margles: What year was this?

TANZER: That would be 1970 approximately.

Margles: After the fair housing act of ’68?

TANZER: I’m not sure, yes it had to be. And then on the Court of Appeals the case that I was best known for was a challenge to the Bottle Bill brought by beer distributors.

Brunner: Yes, the American Can Co. v. OLCC.

TANZER: Yes, and that case was an interstate commerce challenge. We don’t see interstate commerce clause cases. They just don’t exist. They brought in constitutional law professors for amicus briefs and all of that. I wrote the opinion on that case, Herb assigned it to me, it was one of my very first opinions, upholding the Bottle Bill. They didn’t take it to the Supreme Court because (I infer or deduce) they didn’t want the Supreme Court to adopt my opinion. They would rather that it stay as a Court of Appeals decision. But that case was in all the constitutional law casebooks. It was usually the only one there that was not from the U.S. Supreme Court. I was very pleased with that and very proud of it. Then, as long as I am bragging…

Brunner: Please.

TANZER: … I wrote a couple, particularly for the Springfield Education Association v. Springfield School District. I really took the lead in administrative law. Hans was the brains of it. He had a mind that was really admirable. But he was not always as articulate as he might be. I sort of took his theories and wove them together into an understandable whole. That was much my reputation on the Supreme Court, on administrative law, authoring opinions like that.

Brunner: What was that case concerning?

TANZER: You know, I don’t even remember anymore what the factual dispute was. The important thing in that case was how a court reviews an administrative determination and how to interpret the Oregon Administrative Procedures Act so that, if an agency decides a fact, what does an appellate court look to about that fact? How does it review decisions of law by the agency? What is for the agency and what is for the court? It became a roadmap. It is probably the case that the lawyers cite most. And they are still citing that opinion.

Brunner: When was that opinion?

TANZER: That would have been in 1982 or ’81.

Brunner: So you have got Thornton v. Hays, which was the…?

TANZER: That was the Beach Case! [laughs] Oh you are right on top of it.

Brunner: That’s right. And the American Can Company v. OLCC, you said that was concerning interstate commerce?

TANZER: Yes, it is called the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution. That is the clause that gives congress, in the Federal Government, power over interstate commerce. And by implication, denies the states the right to interfere with interstate commerce in any way. The bottle bill had a financial cost to the purchase and regulating of bottles being used in the beer industry. This affected the way that beer flowed across interstate lines.

Brunner: Since the beer was coming from another state into this state, we couldn’t charge them?

TANZER: Yes, that Oregon was putting a burden on Anheuser-Busch or Miller and giving an advantage to local brewers. The Oregon brewers didn’t have to ship their bottles all the way back to St. Louis or wherever it might be, Milwaukee.

Brunner: So you would get the deposit and then the bottle would be sent back to Milwaukee. It wouldn’t be processed here?

TANZER: That’s right.

Brunner: OK. That makes sense.

TANZER: No. It didn’t [laughter]. That was their argument.

Brunner: No, I mean it makes sense to me now.

TANZER: OK, well I’m glad you weren’t on the court [laughter].

Brunner: At the Supreme Court you also worked on the Apodaca case.

TANZER: That was a case that, as Solicitor General, I argued on behalf of Oregon in the US Supreme Court. That was a criminal appeal. I first argued that case to a panel that included Hugo Black and John Harlan, who were both historically significant justices – great justices. It was an unusual case because it dealt with juries. The question wasn’t the right to a jury but Oregon, it turned out, was almost unique in that it allowed super majority verdicts instead of requiring unanimity, which almost all states do. We allowed ten to twelve in felony cases to convict. That was challenged and I represented the state. It is not like search and seizure, where a body of law was developed where the question is, if you have probable cause and you go into the trunk of a car and open a suitcase, what if there is a box in the suitcase… you see, each case leads to another refinement. There was no body of precedent for this. So it required (in my mind) going back to the Twelfth Century, when juries started being formed, and looking at ancient practices and carrying that forward, not just looking back to what was decided last year and building on it. So in that sense it was really an interesting case to work. The court was unable to decide the case. There is a book out called The Brethren, which was one of the first of the so-called “inside the court” books. I was able to read what happened in the court, which is very unusual. They were unable to decide it and, as is the court’s practice, they set it for re-argument the following October. Harlan and Black were both gone and new justices were appointed. That was the first case argued to Justice Rehnquist and Justice Powell. I argued their first case. [laughs] And I won five to four. That was a very interesting time. Because of the posture of the case being so new, it was very intellectually challenging. I could have argued the other side and done just as well. My opponent was a very decent guy from Washington, D.C. whom I enjoyed working with.

Margles: How many times did you go to the US Supreme Court?

TANZER: I only argued those two cases. I wrote briefs a few times, particularly for Lee Johnson to argue.

Brunner: Just for my own clarity, is Oregon one of the only states that does not require a majority to convict in a felony? Is that still the case?

TANZER: We don’t require unanimity. We require a majority.

Brunner: But you don’t need 12?

TANZER: No, except in capital cases. There you do.

Brunner: Is Oregon still one of the only states?

TANZER: As far as I know. There was a lot of discussion and, on request (I didn’t promote it) I wrote a couple of articles for bar journals here and there about it. There is a lot of discussion about it in other states, particularly in California but it never changed. I am not a champion of it; I was a defender of it.

Brunner: Did you cite some of that Twelfth Century precedent when you were arguing?

TANZER: Absolutely, sure. Originally, juries were composed of witnesses and people who knew the parties involved. It was the exact opposite of what we do now.

Margles: The impartial jury, wow.

TANZER: Emily Simon, I don’t know if you know Emily.

Margles: Oh, I know her very well.

TANZER: Emily once told a story of traveling, I think it was in Western China. She witnessed a bicycle rider hit a pedestrian and knocked him over and hurt him a little bit. So all of the people who had witnessed it gathered together, talked it over and decided that the pedestrian was entitled to compensation for his injury, and how much. The bike rider went home and got the money and came back and paid the guy and it was over. That is really pretty much how it worked in Twelfth Century England. It was the people who saw it and who knew the parties and could tell who was telling the truth and who wasn’t. That is the way it started. Then I sort of followed the transformation of the system to its modern form. It was a really interesting case and really unique in the sense that it went so far back.

Brunner: Why was it challenged in the first place? Why did it go to the Supreme Court?

TANZER: Well, there was a fellow who didn’t like having been convicted [laughter] and the public defender appealed for him. He appealed on that basis; thought he would give it a try. The Oregon Supreme Court gave him short shrift so he appealed to the US Supreme Court and presented to them an interesting case too because it was an anomaly in American practice, in Anglo-American practice. Intellectually it is kind of a natural for the US Supreme Court to take.

Brunner: All right. Now I am going to go back and listen to this and say, “Why didn’t I ask him that?”

TANZER: You know my phone number.

[Judith Margles leaves the room – there are some goodbyes]

Brunner: What have I missed? What have I not asked about that you think I should have?

TANZER: There is something that I have thought a lot about. You know how you always think of what you should have said afterward and that you should have said it? I did a little pre-taped interview to be used as a pre-show for [the stage play of] The Chosen. And I started thinking about it, but I don’t know if it applies here. It is more religious thinking than legal thinking.

Brunner: No, go right ahead.

TANZER: There is something I wish I had said in that interview. He [the unknown interviewer] had asked me about the affect of the Holocaust on my thinking. Well, I had always had some doubts about religion because when I was a little boy at the 1st Street Shul, where I was raised, they got English translations of prayers one year. They changed prayer books. I started reading the English side (I knew how to daven in Hebrew) and I thought, “Why am I saying these things? Why am I asking to be forgiven for coveting our neighbors’ wives and sleeping with the animals? Why am I saying this?” So I began to have my doubts. Finally, the Holocaust got to me. The idea of the Holocaust seemed utterly inconsistent with the idea of a “good and powerful God.” That was finally the clincher where I fell away from religion and became a non-observant Jew, though I hope I am still thought of as part of the Jewish community, because I still feel that way. My brother, whom we discussed, and for whom I have always had not just brotherly love but admiration, he looked at it in exactly the opposite way, I deduce. He saw in the Holocaust, an attempt to destroy something valuable, and he thought it was his duty to attempt to maintain the tradition as a Jew – the exact opposite conclusion from mine. And he led that kind of life, while I led a secular life. This was something I have just recently figured out. That whole business about how are you a Jew when you don’t believe in Judaism has always been a question in my mind. It is something to wrestle with.

Brunner: I think that has been a question for a long time: the cultural aspect as opposed to the religious aspect.

TANZER: Yes. And clearly there were Jewish values that entered into my work. When I talk about things that I have achieved and things that I have worked for, I am much a product of the things I learned from my parents and in Sunday school. Yet the religious part didn’t take. I don’t think the Holocaust was the reason, but it was the clincher. That was a very different reaction from Hershal’s. He took the opposite path.

Brunner: What do you think of his reaction to it?

TANZER: I respect it. I can’t say I agree with it but I respect it, and I know that it was profound for him. For him it is the duty of each generation to preserve the tradition. I went through a lot of guilt because I wasn’t fulfilling my responsibility in that respect.

Brunner: Going back to one of your quotes, I don’t know how true that assertion is on your part. When you were talking about the Civil Rights cases that you had worked on, one of the things you said was that you thought Sunday school and Passover Seders were… let me read it to you, “When I was taught at home and at Sunday school and at Passover Seders of the historical oppression of the Jews there was always an important subscript that the oppression of any people or race or religion, even in America, was as immoral and dangerous as what had happened to the Jews in Europe and in ancient Egypt. I was taught that the vigilance was a duty, particularly for Jews, that extended to all people.”